by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

Uppsala Cathedral; Credit – Av Andrew Friberg – Eget arbete, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62401111

Originally, a Roman Catholic church, Uppsala Cathedral in Uppsala, Sweden became a Lutheran church during the Protestant Reformation in Sweden. It is now a Church of Sweden, the Evangelical Lutheran national church in Sweden. Uppsala Cathedral is the seat of the Archbishop of Uppsala, the Primate of Sweden.

The church at Gamala Uppsala (Old Upsala) as it looks today; Credit – By Lestat (Jan Mehlich) – From Polish Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=459228

At the end of the Viking Age (circa 793 – 1066), the Viking temple at Gamla Uppsala (Old Uppsala) was replaced by a Christian church. The date of construction of the church at Gamala Uppsala is unknown but a Bishop of Uppsala was appointed in 1123. After the church was damaged by a fire, local church officials sought permission from Pope Alexander IV to build a larger church nearby. Permission was given with the condition that the location name of Uppsala would be preserved. A new site was chosen in nearby Östra Aros whose name was changed to Uppsala.

Construction started in 1272 on the site of an earlier stone church dedicated to the Holy Trinity. This earlier church is related to the story of Saint Erik IX of Sweden (reigned circa 1156 – 1160), Sweden’s patron saint who is buried at Uppsala Cathedral. Magnus Henriksson, a Danish lord and a claimant to the throne of Sweden, gathered an army near Östra Aros where Erik planned to attend Mass, in that earlier stone church, on the Feast of the Ascension, May 18, 1160. After Erik attended Mass, he armed himself, and with a few men, went out to meet Magnus’ troops. Erik was pulled off his horse by Magnus’ troops who stabbed him and then beheaded him. Magnus Henriksson reigned for a year as King Magnus II before he was killed.

The church was designed by unknown French architects who supervised the construction until 1281. Progress on the construction was slow because of the cold climate, the plague, and financial difficulties. In 1287, French master builder Étienne de Bonneuil and his assistants traveled to Sweden to work on the cathedral. By the end of the 14th century, the initial plans were completed. However, when the cathedral was consecrated in 1435 by Archbishop Olaus Laurentii, it still was not complete. The cathedral was dedicated to Saint Lawrence (one of the seven deacons of the city of Rome who were martyred in 258) Saint Eric IX of Sweden (the patron saint of Sweden although he was never canonized by the Roman Catholic Church), and Saint Olaf (the patron saint of Norway).

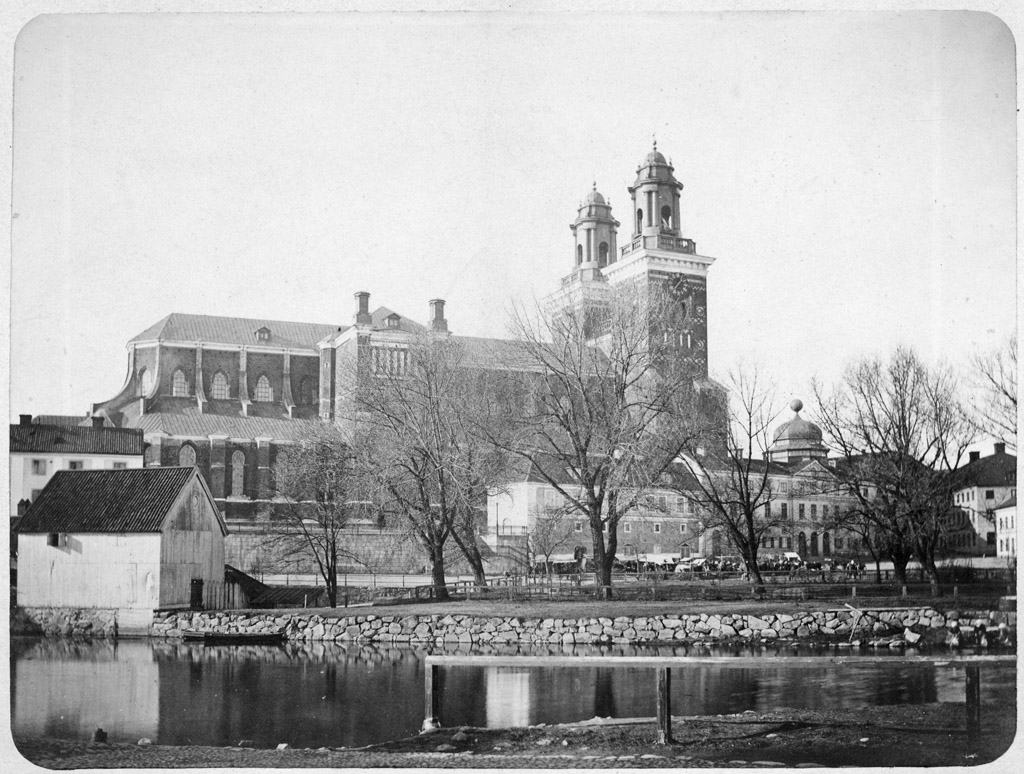

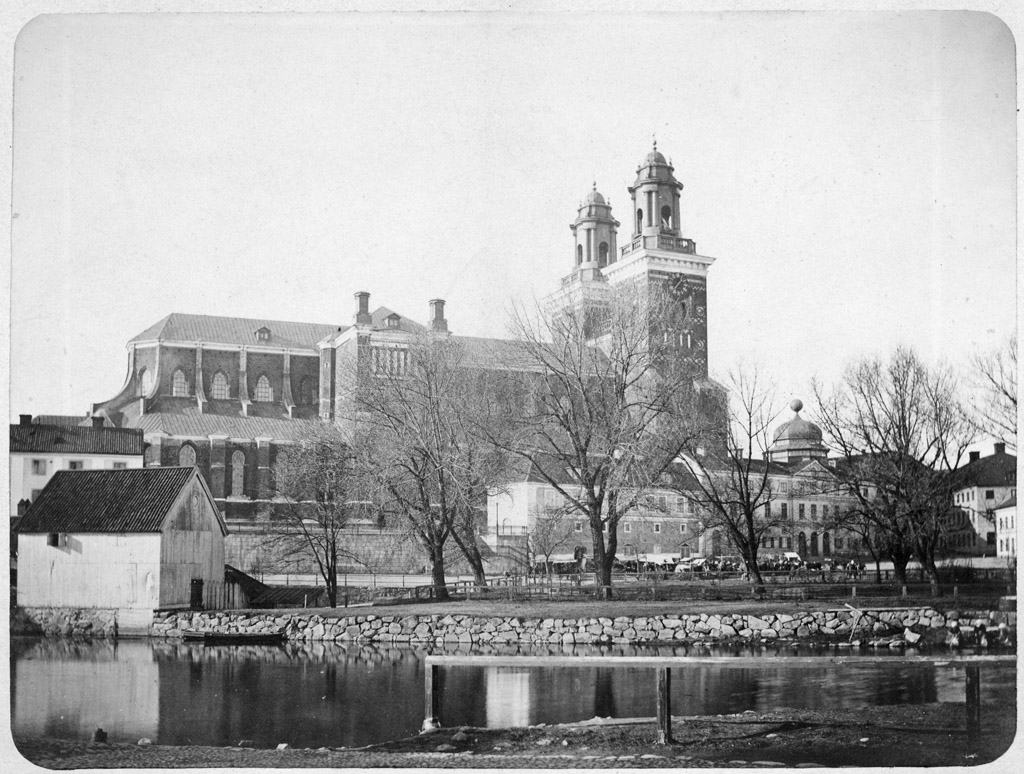

A photograph of Uppsala Cathedral circa 1860, before Zettervall’s restoration; Credit – Wikipedia

Uppsala Cathedral today; Credit – Wikipedia

Over the years, fire damage required some renovations. From 1885 – 1893, the architect Helgo Zettervall oversaw comprehensive restoration work, seeking to give the cathedral a French High Gothic appearance. He added pointed French spires to the towers and in an attempt to give the cathedral a slimmer appearance, Zettervall significantly altered large portions of the medieval outer brick walls. He has been criticized for not respecting the cathedral’s original Brick Gothic style. Further renovation work from 1963 – 1977 led by Swedish architect Åke Porne (link in Swedish) improved the building’s structure and included restoration of the walls and windows. Large portions of Zettervall’s cement additions to the exterior of the cathedral were removed.

********************

The Shrine of Saint Erik IX of Sweden

The shrine of Saint Erik IX of Sweden; Credit – Wikipedia

Saint Erik IX of Sweden is said to have been buried first in the church at Gamla Uppsala (Old Uppsala). In 1273, his remains were transferred to the new cathedral in Uppsala which was still under construction. The gilded silver casket that we see today was made in 1574 – 1579 by King Johan III of Sweden to replace an earlier casket that was melted down when he needed money.

From 2014 – 2016, the remains in the shrine were examined. The researchers were 90% sure that the remains are those of Saint Erik IX of Sweden. Carbon-14 testing matched the date of Erik’s death and the manner of death fits the story of Erik’s death. The remains are from a person who died a violent death, probably decapitation. The remains also show that the person was about 35 years old at the time of his death, was strongly built, healthy, and physically active during his life.

********************

The High Altar

The high altar; By .ky – Inside the church in Uppsala, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4968508

The high altar is used for the cathedral’s most important services. It is also here that all Swedish bishops are ordained. The silver chandelier is from 1647. The large crucifix in silver and crystal was installed in 1976.

Burchard Precht’s altarpiece was in Uppsala Cathedral until Helgo Zettervall removed it during his late 19th-century restoration. The altarpiece is now in the Gustav Vasa Church in Stockholm; Credit – Wikipedia

The altarpieces have changed over the years. From 1725 – 1731, Swedish-German furniture maker and sculptor Burchard Precht worked on a large Baroque altarpiece. It remained in Uppsala Cathedral until it was removed during Helgo Zettervall’s restoration at the end of the nineteenth century. At that time, Precht’s altarpiece was replaced by a neo-Gothic oak altarpiece designed by Swedish architect Folke Zettervall, Helgo Zettervall’s son. However, Precht’s altarpiece can still be seen at the high altar in the Gustaf Vasa Church in Stockholm.

The current altarpiece, a cross in silver and crystal installed in 1976; Credit – By Bo Berggren – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25916597

Folke Zettervall’s altarpiece was removed in 1964. It was replaced for several years by the Skånelaskåpet, a late medieval altar cabinet in oak, made in Brussels during the early 16th century, purchased for the Uppsala Cathedral from Skånela Church in 1912. The current altarpiece consists of a cross in silver and crystal. It was designed by Swedish architect Åke Porne, who led the 1963 – 1977 renovation of Uppsala Cathedral, and was made by Bertil Berggren-Askenström (link in Swedish), a Swedish sculptor and silversmith.

*******************

The Pulpit

The pulpit; Credit – By Szilas – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27571416

The ornate pulpit, the largest in Sweden, was designed by Swedish architect Nicodemus Tessin the Younger and carved by Swedish-German furniture maker and sculptor Burchard Precht. It was a gift from Queen Hedwig Eleonora, the wife of King Karl X Gustav, after the fire of 1702 and completed in 1710. Helgo Zettervall had the pulpit removed during the 1885 – 1893 renovation he led. He wanted to replace the Baroque masterpiece with a pulpit in the Gothic style. However, he did not have the funds for a new pulpit and so Precht’s pulpit returned to its place.

*******************

The Restored Frescoes

Restored frescoes; Credit – Wikipedia

During the Reformation, the medieval frescoes on the walls and ceilings had been whitewashed. Many of these beautiful frescoes were uncovered and restored during Åke Porne’s 1963 – 1977 renovations.

*******************

Coronations

Coronation of Ulrika Eleonora, Queen of Sweden in 1719; Credit – Wikipedia

From 1441 – 1719, all but three Swedish monarchs were crowned at Uppsala Cathedral.

- September 14, 1441 – Christopher of Bavaria, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, crowned King of Sweden

- June 29, 1448 – Karl Knutsson, King of Sweden and Norway, crowned King of Sweden

- July 2, 1448 – Katarina Karlsdotter, second wife of Karl Knutsson

- June 29, 1457 – Christian I, King of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, crowned King of Sweden

- July 3, 1457 – Dorothea of Brandenburg, wife of Christian I

- January 12, 1528 – Gustav I Vasa, King of Sweden

- October 6, 1536 – Margareta Leijonhufvud, second wife of Gustav I Vasa

- June 29, 1561 – Erik XIV, King of Sweden

- July 10, 1569 – Johan III, King of Sweden and his first wife Katarina Jagellonica of Poland

- February 19, 1594 – Sigismund III Vasa, King of Sweden and his first wife Anna of Austria

- March 15, 1607 – Karl IX, King of Sweden and his second wife Christina of Holstein-Gottorp

- October 12, 1617 – Gustavus II Adolphus the Great, King of Sweden

- June 6, 1654 – Karl X Gustav, King of Sweden

- September 28, 1675 – Karl XI, King of Sweden

- March 17, 1719 – Ulrika Eleonora, Queen of Sweden

*******************

Wedding

*******************

Burials

Tomb of King Gustav I Vasa and his first two wives; Credit – Von Skippy13 – Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=726933

Except for Saint Erik IX, all the royal burials at Uppsala Cathedral are members of the family of King Gustav I Vasa. He was the first king of the House of Vasa and is considered the founding father of the modern Swedish state. During the Swedish War of Liberation (1521 – 1523), Gustav Vasa successfully deposed King Christian II from the throne of Sweden, ending the Kalmar Union between Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. On June 6, 1523, Gustav Vasa was elected King of Sweden by the Swedish Riksdag (legislature) and soon all Danish troops were driven out of the country. King Gustav I Vasa ranks among Sweden’s greatest monarchs and some argue that he was the most significant ruler in Swedish history. He ended foreign domination in Sweden, centralized and reorganized the government, cut religious ties to Rome, established the Church of Sweden, and founded Sweden’s hereditary monarchy.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Eric IX of Sweden – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_IX_of_Sweden> [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Uppsala Cathedral – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uppsala_Cathedral> [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Sv.wikipedia.org. 2021. Svenska kröningar – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Svenska_kr%C3%B6ningar> [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Sv.wikipedia.org. 2021. Uppsala domkyrka – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uppsala_domkyrka> [Accessed 7 December 2021].