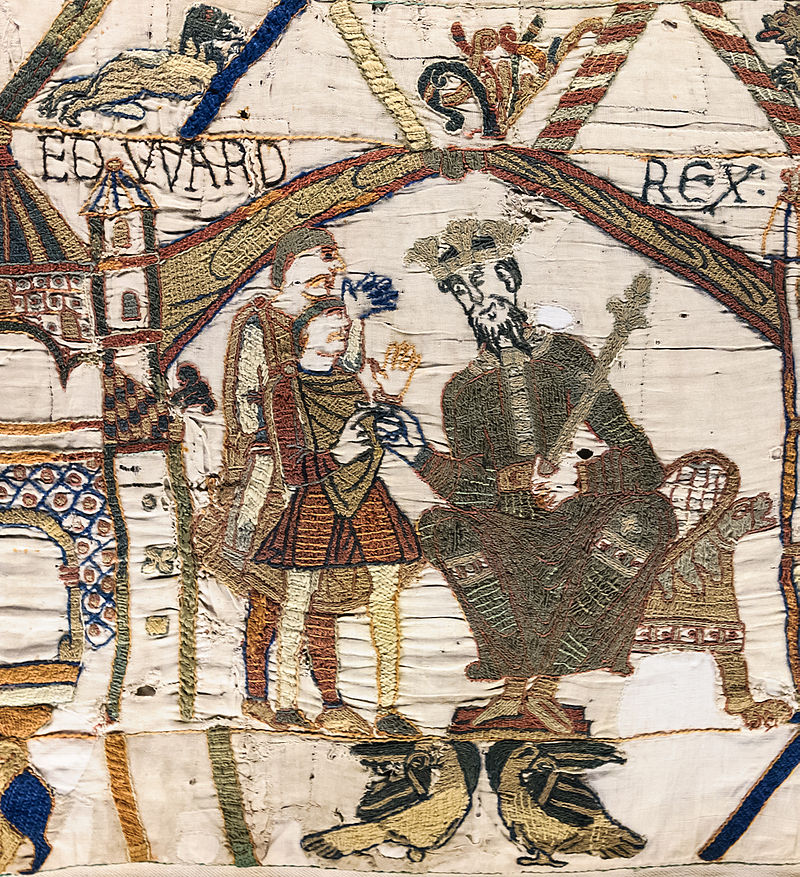

by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

Eleanor of Aquitaine’s effigy; By Adam Bishop – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17048657

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right, Queen of France (the first wife of King Louis VII of France, marriage annulled after 15 years) and Queen of England (wife of King Henry II of England) survived her first husband, her second husband, and eight of her ten children. She was the longest-lived British Queen Consort until the death of Queen Mary, wife of King George V, 749 years later. Currently, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother holds the record for the longest-lived British Queen Consort.

Through some historical detective work, historians deduced that Eleanor was most likely born in 1122 in Poitiers, Bordeaux, or Nieul-sur-l’Autis, all cities in her father’s lands, all now in France. She was the eldest of the three children of William X, Duke of Aquitaine and Aenor de Châtellerault. Eleanor is said to have been named after her mother Aenor and called Aliénor from the Latin alia Aenor, which means “the other Aenor.” It became Eléanor in the French and Eleanor in English.

Eleanor had two siblings:

Eleanor received an education as befitted a noblewoman of her time at the court of Aquitaine, one of the finest courts of the twelfth century, which saw the birth of courtly love and the influence of Occitan language at the various residences of the Dukes of Aquitaine. Eleanor learned Latin, music, literature, riding, hawking, and hunting. Eleanor’s grandfather William IX, Duke of Aquitaine, a lyric poet in the Occitan language, was the earliest troubadour whose work has survived. In 1127, Eleanor’s grandfather died and her father became Duke of Aquitaine. Eleanor’s brother and mother died in 1130, and the eight-year-old Eleanor became her father’s heir.

However, the reign of Eleanor’s father was short. In 1137, William decided to make a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela to atone for his sins. Before leaving, he made his vassals swear to respect the rights of his heir, Eleanor. At the same time, he put both his daughters under the protection of his lord, King Louis VI of France. Eleanor and Petronilla accompanied their father to Bordeaux, where he left them in the care of the archbishop. William then continued his journey to the Shrine of Saint James of Compostela in the company of other pilgrims. However, William never arrived at his destination because he died on Good Friday, April 9, 1137. 15-year-old Eleanor became the Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right, and became the most eligible potential bride in Europe.

King Louis VI of France was not in good health. The heir to the French throne was his second son, Louis. The devout Louis had been destined for the priesthood, but this changed when his elder brother Philip was killed in a horrible accident six years earlier. When the ailing Louis VI heard that his vassal William X, Duke of Aquitaine died, leaving a wealthy female heir, he saw an opportunity and declared that his son Louis would marry Eleanor. In this way, Louis VI would add the large territory of the Duchy of Aquitaine to his family’s holdings in France. Eleanor and Louis were married on July 25, 1137, in the Cathedral of Saint-André in Bordeaux. Immediately after the wedding, the couple was enthroned as Duke and Duchess of Aquitaine. However, Aquitaine would remain independent of France until Louis and Eleanor’s oldest son became both King of France and Duke of Aquitaine. Therefore, Eleanor’s holdings would not be merged with France until the next generation. As a wedding gift, Eleanor gave Louis a rock crystal vase that her grandfather William IX, Duke of Aquitaine had given her. Louis subsequently gave the vase to the Abbey of Saint-Denis, now a basilica, the traditional burial place of the French kings and consorts. The vase is displayed at the Louvre and is the only object connected with Eleanor of Aquitaine that still survives.

The rock crystal vase on display at the Louvre; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

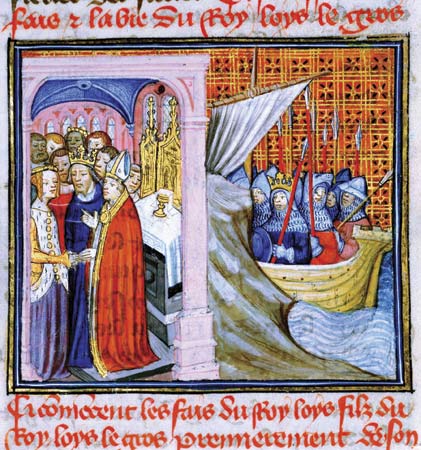

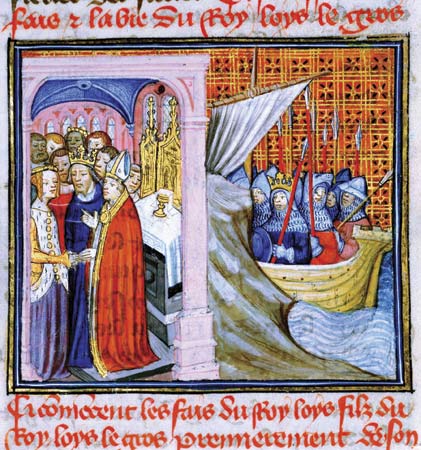

At left, a 14th-century representation of the wedding of Louis and Eleanor; at right, Louis leaving on Crusade; Credit – Wikipedia

Eleanor and Louis VII had two children, both daughters:

A week after Eleanor and Louis’s wedding, King Louis VI died, and Eleanor’s husband was King Louis VII of France, and Eleanor was Queen of France. Eleanor and Louis were very incompatible. Eleanor was high-spirited, and Louis led a life strongly influenced by his monastic youth. In 1147, Louis VI and Eleanor left France to participate in the unsuccessful Second Crusade. The expedition to the Holy Land came at a great cost to the royal treasury and military. It also precipitated a conflict with Eleanor that led to the annulment of their marriage.

Perhaps the marriage to Eleanor might have continued if the royal couple had produced a male heir, but this had not occurred. While in the Holy Land, Eleanor and Louis visited her paternal uncle Raymond of Poitiers, Prince of Antioch. Louis became suspicious of the attention Raymond gave Eleanor, and the long conversations they enjoyed. Raymond was only seven years older than Eleanor, and they had been close during childhood, however, an affair between uncle and niece was suspected by many. Raymond and Eleanor also differed with Louis regarding the tactics of the Second Crusade. Even before the Crusade, Eleanor and Louis were becoming estranged, but the situation now had worsened. Due to their disagreements, Louis and Eleanor left the Holy Land on separate ships.

The ships of Eleanor and Louis were attacked and besieged by storms. Neither was heard from for over two months, and they were given up for dead. Eventually, Eleanor and Louis turned up in Calabria, and they decided to go to the Pope, hoping for a marriage annulment. However, Pope Eugene III did not grant an annulment. Instead, he attempted to reconcile Eleanor and Louis, confirming the legality of their marriage. The Pope arranged events so that Eleanor had no choice but to sleep with Louis in a bed specially prepared by the Pope. Their second child was conceived, but it was another daughter.

Louis knew the marriage should end. He had no heir, Eleanor wanted an end to the marriage, and she would be supported by her vassals. On March 21, 1152, the four archbishops, with the approval of Pope Eugene, granted an annulment on the grounds of consanguinity within the fourth degree. Eleanor was Louis’ third cousin once removed and shared common ancestry with Robert II of France. Their two daughters were declared legitimate.

Eleanor then set out for her own land in Poitiers. However, two would-be suitors for a wealthy heiress, Theobald V, Count of Blois, (the future husband of Eleanor’s daughter Alix of France) and Geoffrey, Count of Nantes (the brother of Eleanor’s 2nd husband, the future King Henry II, of England) tried to kidnap her to marry her to claim her lands. As soon as she reached Poitiers, Eleanor contacted the young Henry, Duke of Normandy, the future King Henry II of England, who had been fighting for the English throne, asking him to marry her at once. Henry knew it was a good deal because of Eleanor’s land. Even though Henry was more closely related to Eleanor than Louis, 19-year-old Henry married 30-year-old Eleanor eight weeks after the annulment, on May 18, 1152, in Bordeaux in Eleanor’s Duchy of Aquitaine.

Eleanor and Henry had eight children and were the grandparents of many sovereigns and queen consorts.

- William IX, Count of Poitiers (1153 – 1156), died in childhood

- Henry the Young King (1155 – 1183), married Marguerite of France, no children

- Matilda of England, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria (1156 – 1189), married Heinrich the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, had five children, including Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor

- King Richard I of England (1157 – 1199), married Berengaria of Navarre, no children

- Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany (1158 – 1186), married Constance, Duchess of Brittany, had three children

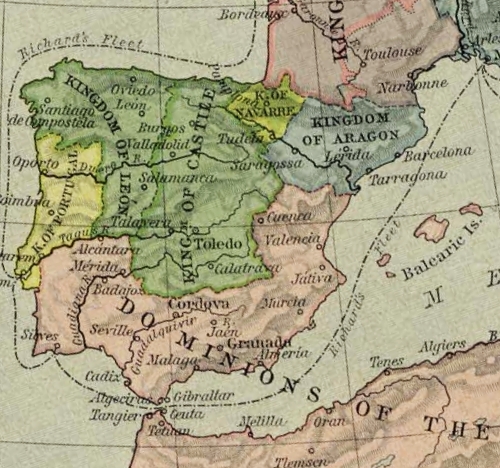

- Eleanor of England, Queen of Castile (1162 – 1214), married King Alfonso VIII of Castile, had twelve children including King Enrique I of Castile; Berengaria, Queen Regnant of Castile and Queen of León; Urraca, Queen of Portugal; Blanche, Queen of France, and Eleanor, Queen of Aragon

- Joan of England, Queen of Sicily (1165 – 1199), married (1) King William II of Sicily, no surviving children (2) Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, had two children, Joan died in childbirth with her third child who also died

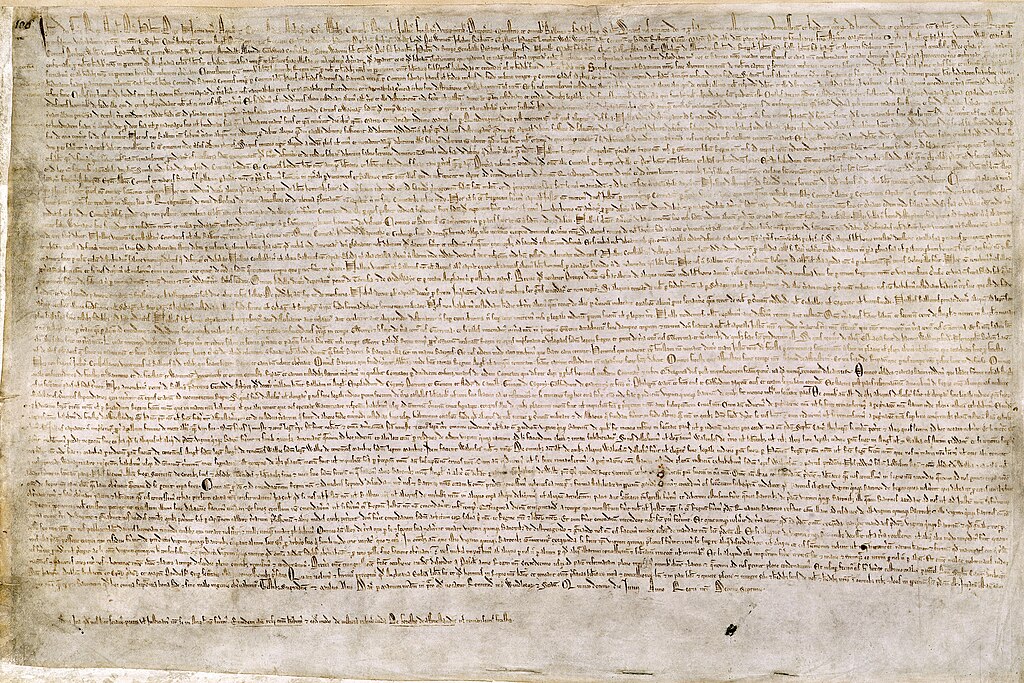

- King John of England (1166 – 1216), married 1) Isabella, 3rd Countess of Gloucester, marriage annulled, no children (2) Isabella, Countess of Angoulême; had five children, including King Henry III of England; Joan of England, Queen of Scots, and Isabella of England, Holy Roman Empress

13th-century depiction of Henry and his legitimate children: (l to r) William, Young Henry, Richard, Matilda, Geoffrey, Eleanor, Joan, and John; Credit – Wikipedia

Eleanor’s second husband Henry, Duke of Normandy was born on March 5, 1133, in Le Mans, the capital of the County of Maine, now in France. He was the eldest of the three sons of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine and Empress Matilda (sometimes called Maud). Henry’s mother was the widow of Heinrich V, Holy Roman Emperor, and she used her style and title from her first marriage for the rest of her life. More importantly, Matilda was the only surviving, legitimate child of King Henry I of England and Duke of Normandy.

Matilda’s only sibling and her father’s heir had drowned when his ship sank, leaving Matilda as the heir to the throne of England. On Christmas Day of 1226, King Henry I of England gathered his nobles at Westminster, where they swore to recognize Matilda and any future legitimate heir she might have as his successors. That plan did not work out. Upon hearing of Henry I’s death in 1135, Stephen of Blois, one of Henry I’s nephews, quickly crossed the English Channel from France, seized power, and was crowned King of England on December 22, 1135. This started the terrible civil war between Stephen and Matilda, known as The Anarchy. The future Henry II was two years old when this civil war started, and it was to affect his childhood as England did not see peace for 18 years.

The civil war between first cousins, Empress Matilda and Stephen of Blois, King of England since 1135, dragged on for many years. Stephen unsuccessfully attempted to have his son Eustace recognized by the Church as the next King of England. By the early 1150s, most barons and the Church wanted long-term peace. Ironically, Stephen’s son Eustace died the same day that Eleanor and Henry’s eldest son William was born. Although William died when he was three years old, the irony of the birth and the death must have been noticed at the time.

When Henry re-invaded England in 1153, neither side’s forces were eager to fight. After limited campaigning and the siege of Wallingford, Stephen and Henry agreed upon a negotiated peace, the Treaty of Winchester, in which Stephen recognized Henry as his heir. Stephen died on October 25, 1154, and Henry ascended the throne as King Henry II, the first Angevin King of England. Henry was crowned at Westminster Abbey on December 19, 1154. His wife Eleanor was crowned with him.

12th-century depiction of Henry and Eleanor holding court; Credit – Wikipedia

Eleanor and Henry’s marriage was reputedly tumultuous and argumentative. Henry was not faithful, and Eleanor was somewhat ambivalent towards his affairs, as evidenced by her raising one of Henry’s illegitimate sons Geoffrey, the future Archbishop of York, in her household. By late 1166, Henry’s notorious affair with Rosamund de Clifford had become known, and Eleanor’s marriage to Henry appears to have become permanently strained. As their children grew up, the couple grew further apart, and Eleanor seemed to take delight in backing one son and then another against Henry.

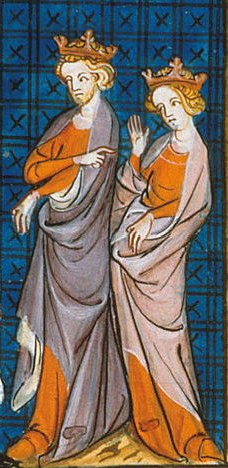

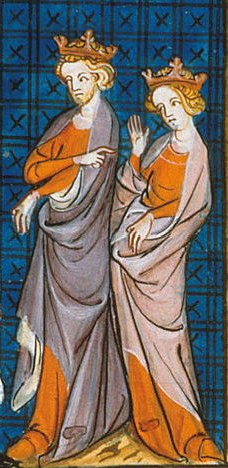

Henry and Eleanor; Credit – Wikipedia

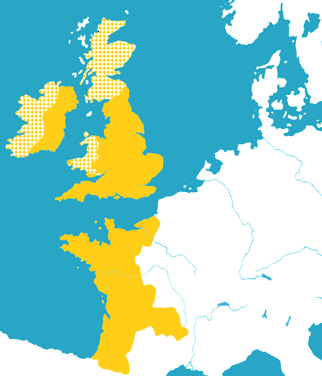

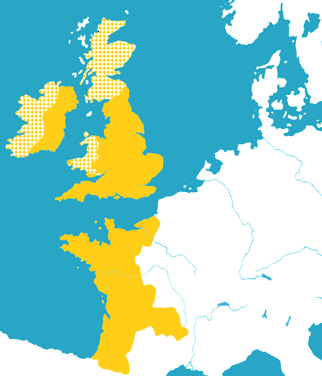

During Henry II’s reign, the lands of the Angevin Empire consisting of an area covering half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and Wales.

Angevin Empire around 1172, solid yellow shows Angevin possessions, checked yellow shows areas where there was Angevin influence; By Cartedaos (talk) 01:46, 14 September 2008 (UTC) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4781085

The last part of Henry’s reign was taken up by disputes with and between his sons, often encouraged by Eleanor. As Henry II’s children grew up, tensions over the future inheritance of the empire began to emerge, encouraged by King Louis VII of France and then his son King Philippe II of France. In 1173, Henry the Young King rebelled in protest and was joined by Eleanor and his brothers Richard and Geoffrey. France, Scotland, Flanders, and Boulogne allied themselves with the rebels. Henry II eventually defeated the revolt and had Eleanor imprisoned for the next sixteen years for her part in inciting their sons. In 1182–83, Henry the Young King had a falling out with his brother Richard when Richard refused to pay homage to him on the orders of King Henry II. As he was preparing to fight Richard, Henry the Young King became ill with dysentery (also called the bloody flux), the scourge of armies for centuries, and died. In 1186, Eleanor and Henry’s third son Geoffrey was trampled to death during a jousting tournament in Paris.

By the time Henry II turned 56 in 1189, he was prematurely aged. Two sons were left: Richard, the second son, Eleanor’s favorite and the heir since his elder brother’s death, and John, the youngest child, Henry’s favorite. King Philip II of France successfully played upon Richard’s fears that Henry would make John the next King of England, and a final rebellion broke out in 1189. Decisively defeated by Philip and Richard and suffering from a bleeding ulcer, Henry retreated to his favorite residence, the Château de Chinon in Anjou. There he was told that John had publicly sided with Richard in the rebellion, and this broke his heart. Only his illegitimate son Geoffrey, Archbishop of York, was at his father’s deathbed, and it moved Henry to observe that his illegitimate son had proved more loyal than his legitimate sons: “Baseborn indeed have my other children shown themselves. This alone is my true son.” King Henry II of England died at the Château de Chinon on July 6, 1189, at the age of 56, and was succeeded by his son Richard.

Richard was not in England when his father died. One of Richard’s first acts as king was to send William Marshal to England with orders to release Eleanor from her imprisonment, but when Marshal arrived, he found that she had already been released. Eleanor traveled to Westminster and received the oaths of fealty from lords and bishops on behalf of Richard. She ruled England in Richard’s name until his arrival in August of 1189, signing herself “Eleanor, by the grace of God, Queen of England”. However, Richard spent little time in England during his ten-year reign, perhaps as little as six months. Most of his reign was spent on Crusade, in captivity, or in actively defending his lands in France.

Eleanor escorted Richard’s bride Berengaria of Navarre on part of her journey to Cyprus, where he was preparing for the Third Crusade and where the couple married. Eleanor ruled England as regent while Richard was on the Third Crusade. Later, when Richard was captured in Germany on his way home from the crusades, Eleanor negotiated his ransom by going to Germany. In late March 1199, when Richard was dying of gangrene from an arrow wound, Eleanor made her way to his deathbed. Richard died in his mother’s arms on April 6, 1199, and the last son John became king.

On April 1, 1204, Eleanor died at Fontevrault Abbey in Fontevraukt, near Chinon, in the Duchy of Anjou, now in France, at the age of 82. In 1562, the abbey church was pillaged and looted by the Huguenots during the Protestant Reformation. There are stories that the royal remains were thrown into a nearby river and also that the monks reburied them in a secret location. However, Eleanor’s effigy, showing her reading a Bible, survived and can still be seen.

Eleanor’s effigy next to Henry’s effigy; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

In popular culture, Eleanor, Henry II, and their family are the subject of plays, films, and historical fiction. Eleanor, Henry, and their sons Richard, Geoffrey, and John are characters in James Goldman‘s 1966 play The Lion in Winter and in the 1968 film adaptation of the play with Peter O’Toole playing Henry and Katharine Hepburn in an Academy Award-winning role as Eleanor.

The late American historical fiction author Sharon Kay Penman‘s excellently researched and highly recommended Plantagenet Series deals with Eleanor, Henry II, and their family.

- When Christ and His Saints Slept (1995) introduces the beginnings of the Plantagenet dynasty as Empress Matilda (Penman uses Maude) fights to secure her claim to the English throne.

- Time and Chance (2002) continues the story of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine and focuses on the rift between Henry II and Thomas Becket.

- Devil’s Brood (2008) opens with the conflict between Henry II, his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, and their four sons, which escalates into a decade of warfare and rebellion pitting the sons against the father and the brothers against each other while Eleanor spends the period imprisoned by Henry.

- Lionheart (2011) focuses on Richard the Lionheart’s Crusades in the Holy Land and on what happened to Eleanor when she was finally released after spending sixteen years in confinement that was ordered and enforced by her husband.

- A King’s Ransom (2014) is about the second half of Richard’s life, during and following his imprisonment, ransom, and life afterward.

Penman also wrote a series of mysteries set in the reigns of her sons Richard and John in which the fictional “detective” Justin de Quincy works for Eleanor of Aquitaine in the later years of her life.

- The Queen’s Man (1996)

- Cruel as the Grave (1998)

- Dragon’s Lair New York (2003)

- Prince of Darkness New York (2005)

British historical fiction author Elizabeth Chadwick wrote a series of three novels about Eleanor’s life. Chadwick uses Eleanor’s original name, Alienor, and her research, like Penman’s, is impeccable.

- The Summer Queen (2013) deals with Eleanor’s early life and her time as Queen of France.

- The Winter Crown (2014) deals with Eleanor’s marriage to Henry II of England, their children, and the family rebellion.

- The Autumn Throne (2016) deals with Eleanor’s imprisonment after the family rebellion and her later life.

England: House of Angevin Resources at Unofficial Royalty

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.