by Susan Flantzer

- Raymond Asquith and Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel

- Timeline: September 1, 1916 – September 30, 1916

- A Note About German Titles

- September 1916 – Royals/Nobles/Peers/Sons of Peers Who Died In Action

Note: While researching the deaths for September 1916, I noticed that a lot of British soldiers were killed in action on September 15, 1916, and I wondered why. It was the first time in history that three Coldstream Guard battalions from the British Army had attacked together. Seventeen officers and 690 other ranks advanced into the Battle of the Somme, that dreadful battle that lasted from July 1 – November 18, 1918 resulting in more than 1,300,000 soldiers from all countries involved dead or wounded. Tragically, British fourteen officers and 469 other ranks were killed on September 15, 1916. The British peers and sons of peers listed below were some of the fourteen officers killed. One of the officers killed was the eldest son of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom at that time. Another was the great uncle of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall.

**********************************************************

In September of 1916, there were two high-profile deaths in battle: Raymond Asquith, the eldest son of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom at that time, and Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel, a nephew of the German Emperor and also a great-grandson of Queen Victoria.

Raymond Asquith

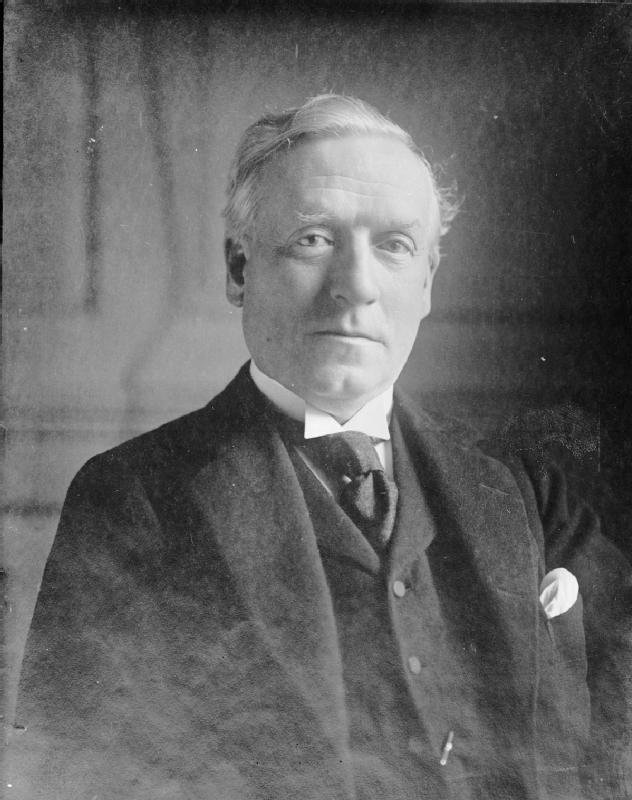

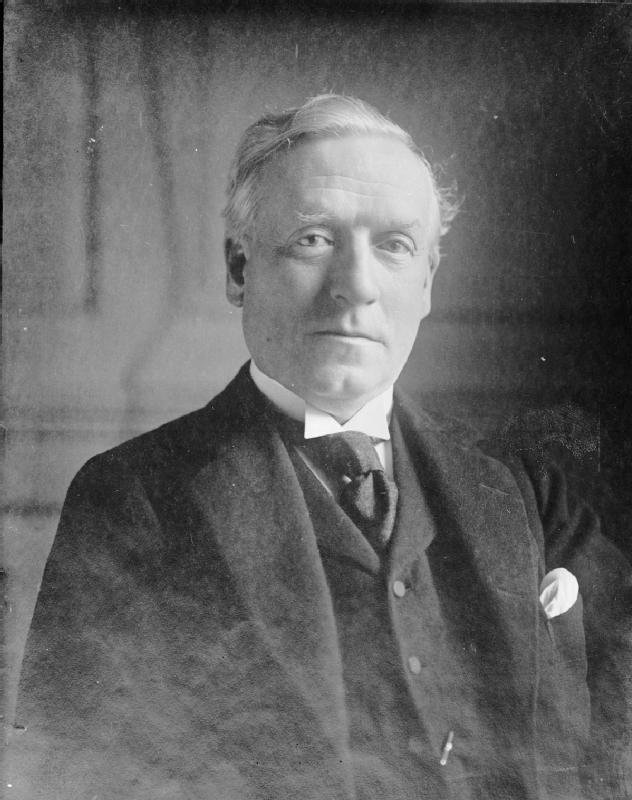

Raymond Asquith; Photo Credit – www.findagrave.com

Raymond Asquith was born on November 6, 1878 in Hampstead, Middlesex, England. He was the first child of Herbert Henry Asquith and his first wife, Helen Kelsall Melland, daughter of a Manchester doctor. Herbert Henry Asquith came from a middle class family and had won a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford. At the time of Raymond’s birth, Asquith was just starting what would become a prosperous law career. Asquith was elected to Parliament in 1886. By 1892, Asquith was serving in the Cabinet as Home Secretary. Asquith continued to rise, and served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from April 5, 1908 – December 5, 1916. In 1925, after Raymond’s death, his father Herbert Henry Asquith was created 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith.

Herbert Henry Asquith, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Raymond’s parents had five children before his mother died in 1891 of typhoid fever. In 1894, Raymond’s father made a second marriage to Margot Tennant. Five more children were born from this marriage, but only two survived childhood.

Raymond’s siblings:

- Herbert Asquith (1881 – 1947), poet, novelist and lawyer, married Lady Cynthia Charteris, also a writer

- Arthur Asquith (1883 – 1939)

- Violet Asquith Bonham Carter, created a life peer as Baroness Asquith of Yarnbury (1887 – 1969), married Sir Maurice “Bongie” Bonham Carter, her father’s Principal Private Secretary, grandmother of the actress Helena Bonham Carter

- Cyril Asquith, Baron Asquith of Bishopstone (1890 – 1954), created a life peer, married Anne Stephanie Pollock

Raymond’s half-siblings:

Raymond attended Summerfield, a boys’ independent day and boarding preparatory school in Summertown, Oxford as did some of his brothers. He then continued his education at Winchester College in Winchester, Gloucestershire, a 600 year old a private school for boys in the British public school tradition. At Winchester College, Raymond won the Queen’s Gold Medal for Latin Essay and the Warden and Fellows’ Prizes for Greek Prose and Verse. In 1897, Raymond began his studies at Balliol College, Oxford and graduated with first-class honors. He was elected a fellow of All Souls College, Oxford in 1902, While at Oxford, Raymond was a member of “the Coterie,” a group of Edwardian socialites and intellectuals.

In 1904, Raymond was called to the bar by the Inner Temple and started to lay the foundations of a successful law practice. He was engaged as junior counsel in the North Atlantic Fisheries Arbitration and in the inquiry into the loss of the Titanic. Shortly before the war he was appointed a junior counsel to the Inland Revenue and adopted as prospective Liberal Candidate for Parliament for Derby.

On July 25, 1907, Raymond married Katharine Frances Horner. The couple had three children:

Katharine Frances Asquith (née Horner); Raymond Asquith by Lady Ottoline Morrell, vintage snapshot print, 1913, NPG Ax140417 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Julian, Raymond’s only son, was born a few months before his father’s death. He was always known as “Trim”. Raymond referred to his newborn son as “Trimalchio” (a character in Petronius’s Satyricon) in a letter written from the Front on the day after the baby’s birth. Raymond did get to see his newborn son while on leave from the war. Julian succeeded his grandfather in 1928 as the 2nd Earl of Oxford and Asquith. He lived a long life, dying in 2011 at the age of 94. Julian’s son, Raymond, succeeded him as the 3rd Earl of Oxford and Asquith.

Telegraph: Obituary – The Earl of Oxford and Asquith

Shortly after World War I broke out, Raymond was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 16th (County of London) Battalion, London Regiment. In August of 1915, he was transferred to the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards and assigned as a staff officer, out of combat. However, Raymond requested to be returned to active duty, and the request was granted before the Battle of the Somme. While leading the first half of 4 Company in an attack near Ginchy, France on September 15, 1916, at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, a battle of the larger campaign, the Battle of the Somme, Raymond was shot in the chest. He famously lit a cigarette to hide the seriousness of his injuries so that his men would continue the attack. When Raymond was dying on the battlefield, he gave the doctor his flask to give to his father, Prime Minister Asquith. His father kept the flask by the side of his bed. Raymond, age 37, died while being carried back to the British lines.

Raymond Asquith was buried at Guillemont Road Cemetery in Guillemont, France, near where the Battle of the Somme took place. His headstone is inscribed: “Small time, but in that small most greatly lived this star of England” – the concluding line from Shakespeare’s Henry V, about the warrior king who had died in his thirties after campaigns in France.

A week later, on September 22, 1916, another death in battle touched the Asquith family. Lieutenant The Honorable Edward Wyndham Tennant, eldest son of Edward Priaulx Tennant, 1st Baron Glenconner was killed in action at Guillemont, France during the Battle of the Somme, age 19. Edward was the nephew of Margot Tennant who was the second wife of Raymond Asquith’s father, Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith. Edward and Raymond had been friends and are buried nearby each other.

Grave of Raymond Asquith; Photo Credit – www.findagrave.com

****************************************************************************

Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel

Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel; Photo Credit – www.pinterest.com

Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel was born on November 24, 1893 in Frankfurt-am-Main, Hessen, Germany. He was the oldest of the six sons of Princess Margarethe of Prussia and Friedrich Karl, Prince and Landgrave of Hesse. Through his mother Prince Friedrich Wilhelm was a great grandson of Queen Victoria and a nephew of Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia.

Friedrich Wilhelm had five younger brother, including two sets of twins:

- Prince Friedrich of Hesse-Kassel (1893–1916), unmarried, killed in action during World War I

- Prince Maximilian of Hesse-Kassel (1894 – 1914), unmarried, killed in action during World War I

- Prince Philipp of Hesse-Kassel (1896 –1980), married Princess Mafalda of Savoy, had issue

- Prince Wolfgang of Hesse-Kassel (1896 –1989), married Princess Marie Alexandra of Baden, no issue

- Prince Richard of Hesse-Kassel (1901 – 1969), unmarried

- Prince Christoph of Hesse-Kassel (1901 –1943), married Princess Sophie of Greece (sister of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh), had issue, killed in action during World War II

Hesse-Kassel sons; Photo Credit – Pinterest

The four elder sons all served in World War I: Friedrich Wilhelm and his brother Wolfgang both served in the Thüringisches Ulanen-Regiment Nr.6 of the German Army, and Maximilian and Philipp both served in the 24th Life Dragoons (2nd Grand Ducal Hessian) of the German Army. Twins Richard and Christoph were too young. Maximilian, the second son, had been killed in action when he was severely wounded by British machine gun fire at Saint-Jean-Chappelle, near Bailleul, France on October 13, 1914. See Unofficial Royalty: October 1914 – Royalty and World War I.

On September 12, 1916, 22 year old Prince Friedrich Wilhelm was killed in action in Dobruja, Romania when his throat was slit by an enemy bayonet in close fighting. His brother Wolfgang, who was serving with the same regiment, was brought to view his brother’s body and saw the bloody dagger from the bayonet resting on his brother’s chest

Friedrich Wilhelm’s mother, who lived until 1954, had a number of family tragedies to endure:

-

- Prince Maximilian of Hesse-Kassel: second child, killed in action during World War I on October 13, 1914. See Unofficial Royalty: October 1914 – Royalty and World War I

- Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel: eldest child, killed in action during World War I on September 12, 1916. See Unofficial Royalty: September 1916 – Royalty and World War I

- Princess Mafalda of Savoy: wife of her son Prince Philipp of Hesse-Kassel, daughter of King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, died in Buchenwald concentration camp on August 27, 1944 during World War II. Philipp was also imprisoned in concentration camps after his fall-out with Hitler

- Prince Christoph of Hesse-Kassel: youngest child, killed in action during World War II on October 7, 1943

- Princess Marie Alexandra of Baden: wife of her son Prince Wolfgang of Hesse-Kassel, killed during an American air-raid on Frankfurt am Main on January 29, 1944 during World War II. Marie Alexandra and seven other women, who were all aid workers, were killed when the cellar, in which they had taken refuge, collapsed under the weight of the building

*********************************************************

Timeline: September 1, 1916 – September 30, 1916

- July 1 – November 18 – Battle of the Somme in Somme, Picardy, France

- September 2–6 – Battle of Turtucaia in Turtucaia, Romania (now Tutrakan, Bulgaria), a phase of the conquest of Romania

- September 3–6 – Battle of Guillemont in Guillemont, France, intermediate phase of the Battle of the Somme

- September 5–7 – Battle of Dobrich in Dobrich, Romania (now Dobrich, Bulgaria), a phase of the conquest of Romania

- September 7–11 – Battle of Kisaki in Kisaki, German East Africa (now in Tanzania)

- September 9 – Battle of Ginchy in Gimchy, France, intermediate phase of the Battle of the Somme

- September 12 – December 11 – Monastir Offensive, set up of the Salonika Front in present-day Macedonia, Albania, Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia

- September 12–14 – Battle of Malka Nidzhe in Malka Nidzhe, Gornichevo, Macedonia , a phase of the Monastir Offensive

- September 12–30 – Battle of Kaymakchalan in Kaymakchalan, Greece, a phase of the Monastir Offensive

- September 14–17 – Seventh Battle of the Isonzo in Gorizia, Italy

- September 15–22 – Battle of Flers-Courcelette in Flers and Courcelette, France; the British use armored tanks for the first time in history

- September 17–19 – First Battle of Cobadin in Rasova, Cobadin, and Tuzla Romania, a phase of the conquest of Romania

- September 20 – The Brusilov Offensive in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria (now in Poland and Ukraine) ends with a substantial Russian success

- September 25–28 – Battle of Morval in Morval, France, part of the final stages of the Battle of the Somme

- September 26–28 – Battle of Thiepval Ridge in Thiepval, France (part of the final stages of the Battle of the Somme)

- September 29 – October 5 – Flămânda Offensive in Ryahovo, Ruse Province, Bulgaria, across the Danube from Flămânda, near Oltenița, Romania, a phase of the conquest of Romania

*********************************************************

A Note About German Titles

Many German royals and nobles died in World War I. The German Empire consisted of 27 constituent states, most of them ruled by royal families. Scroll down to German Empire here to see what constituent states made up the German Empire. The constituent states retained their own governments, but had limited sovereignty. Some had their own armies, but the military forces of the smaller ones were put under Prussian control. In wartime, armies of all the constituent states would be controlled by the Prussian Army and the combined forces were known as the Imperial German Army. German titles may be used in Royals Who Died In Action below. Refer to Unofficial Royalty: Glossary of German Noble and Royal Titles.

24 British peers were also killed in World War I and they will be included in the list of those who died in action. In addition, more than 100 sons of peers also lost their lives, and those that can be verified will also be included.

*********************************************************

September 1916 – Royals/Nobles/Peers/Sons of Peers Who Died In Action

The list is in chronological order and does contain some who would be considered noble instead of royal. The links in the last bullet for each person is that person’s genealogical information from Leo’s Genealogics Website. or to The Peerage website. If a person has a Wikipedia page, their name will be linked to that page.

Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel (see article above)

Raymond Asquith (see article above)

- eldest son of Herbert Henry Asquith, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 1908-1916, created 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith in 1925, and his first wife Helen Kelsall Melland

- born November 11, 1878

- married 1907 Katharine Horner, had three children

- Lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion, Grenadier Guards

- killed in action September 15, 1916 in Trones Wood, Ginchy, France during the Battle of the Somme, age 37

- http://www.thepeerage.com/p1148.htm#i11479

Photo Credit – http://www.wakefieldfhs.org.uk/

The Honorable Lieutenant Colonel Guy Victor Baring

The Honorable Captain Henry Archibald Cubitt; Photo Credit – https://www.dorkingmuseum.org.uk

The Honorable Captain Henry Archibald Cubitt

- eldest son of Henry Cubitt, 2nd Baron Ashcombe and Maud Calvert

- born January 3, 1892

- unmarried

- Captain in the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards

- killed in action on September 15, 1916 at Flers, France during the Battle of the Somme, age 24

- two of Henry’s five brothers also died in World War I: Alick on November 24, 1917 and William on March 24, 1918

- Henry is the great uncle of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall. The eldest of his three surviving brothers Roland Cubitt became the 3rd Baron Ashcombe and married Sonia Keppel. Their daughter The Honorable Rosalind Cubitt married Major Bruce Shand and they were the parents of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall

- http://www.thepeerage.com/p6195.htm#i61948

Photo Credit – www.geni.com

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles William Reginald Duncombe, 2nd Earl of Feversham

- son of William Duncombe, Viscount Helmsley (elder son of William Duncombe, 1st Earl of Feversham) and Lady Muriel Chetwynd-Talbot, daughter of Charles Chetwynd-Talbot, 19th Earl of Shrewsbury

- born May 8, 1879

- married 1904 Lady Marjorie Greville, daughter of Francis Greville, 5th Earl of Warwick, had three children

- Lieutenant Colonel in the 21st Battalion King’s Royal Rifle Corps

- killed in action September 15, 1916 at Flers, France during the Battle of the Somme, age 35

- http://www.thepeerage.com/p2288.htm#i22880

The Honorable 2nd Lieutenant Robert Butler Nivison

The Honorable Lieutenant Ronald Herbert Pike Pease

The Honorable Captain Richard Philip Stanhope; Photo Credit – www.britishempire.co.uk

The Honorable Captain Richard Philip Stanhope

Count Alexander Alekseyevich Bobrinsky

Freiherr Hubertus von Loë

Friedrich, Graf von Waldburg zu Wolfegg und Waldsee; Photo Credit – www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de

Friedrich, Graf von Waldburg zu Wolfegg und Waldsee

- son of Prince Maximilian von Waldburg zu Wolfegg und Waldsee and Sidonie, Princess of Lobkowicz

- born May 25, 1895 in Waldsee, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

- killed in action of September 20, 1916 at Rancourt, France during the Battle of the Somme, age 21

- http://www.familienbuch-euregio.eu/genius/?person=244577

Lieutenant The Honrorable Edward Wyndham Tennant; Photo Credit – www.everymanremembered.org

Lieutenant The Honrorable Edward Wyndham Tennant

The Honorable Lieutenant William Alastair Damer Parnell