by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2023

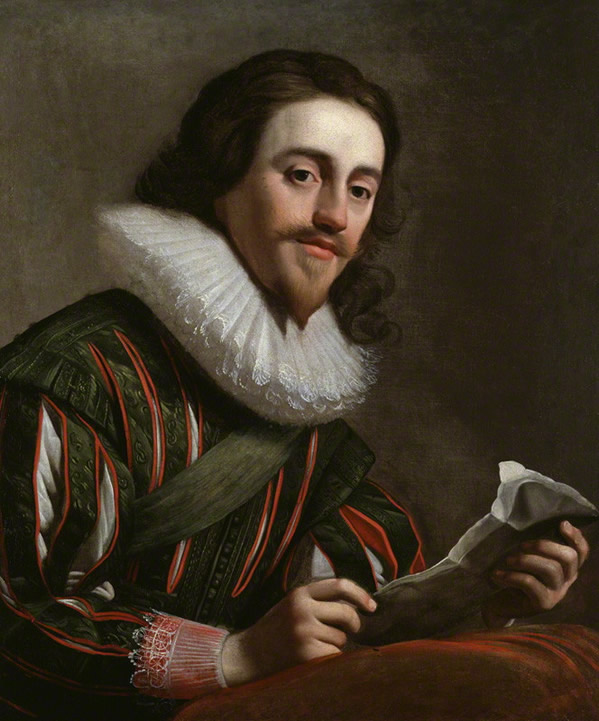

Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk wearing the collar of the Order of the Garter.; Credit – Wikipedia

Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk was the second of the two husbands of Mary Tudor, daughter of King Henry VII of England and sister of King Henry VIII of England. Brandon was born circa 1484, one of the four children of Sir William Brandon and Elizabeth Bruyn.

Charles Brandon had three siblings:

- Robert Brandon (1480 – ?)

- Catherine Brandon (circa 1484 – ?)

- William Brandon (circa 1476 – before 1485)

Charles Brandon’s father Sir William Brandon was the standard banner for Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond (the future King Henry VII) from the House of Lancaster at the Battle of Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485, the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses. When King Richard III of England from the House of York, launched his final charge in the battle, he unhorsed but did not kill, Sir John Cheyne, a well-known jousting champion and Henry Tudor’s personal bodyguard. Sir William Brandon was then killed by King Richard III while defending the standard banner of Henry Tudor. Ultimately, the Battle of Bosworth resulted in King Richard III of England, losing his life and his crown. The battle was a decisive victory for the House of Lancaster, whose leader Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, became the first monarch of the House of Tudor as King Henry VII of England.

In 1494, Charles Brandon’s mother died and the ten-year-old became an orphan. It is likely that Brandon’s uncle Sir Thomas Brandon, who acted as a diplomat for King Henry VII and was also Master of the Horse and a Knight of the Garter, arranged for his nephew to be raised at the court of King Henry VII. At court, Brandon would meet the future King Henry VIII, who was six years younger than Brandon. The two boys would connect due to their shared interests, especially jousting and real tennis, and a lifelong friendship developed. By the time King Henry VII died in 1509 and his son succeeded him as King Henry VIII, Brandon was already a favorite of the new king.

Before his 1515 marriage to Mary Tudor, Charles Brandon had two marriages and one contract to marry:

- 1507: Brandon married Margaret Neville, daughter of John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu (killed at the Battle of Barnet) and Isabel Ingoldesthorpe, no children, the marriage was declared void about 1507 by the Archdeaconry Court of London, and later by a papal bull in 1528

- 1508: Brandon married Anne Browne, daughter of Sir Anthony Browne and Eleanor Ughtred. Anne died in 1512. Brandon and Anne had two daughters:

- Lady Anne Brandon (1507 – 1557), married (1) Edward Grey, 3rd Baron Grey of Powis, no children marriage dissolved (2) Randal Harworth, no children

- Lady Mary Brandon (1510 – circa 1542), married Thomas Stanley, 2nd Baron Monteagle, had six children

- 1513: Brandon was contracted to marry Elizabeth Grey, 5th Baroness Lisle but the contract was annulled

On March 4, 1514, King Henry VIII created Charles Brandon Duke of Suffolk. At that time, there were only two other Dukes in the Kingdom of England. That same year, King Henry VIII negotiated a peace treaty with France that included the marriage of his 18-year-old sister Mary Tudor and the 52-year-old twice-married King Louis XII of France who was eager to have a son to succeed him. Mary was not thrilled at the prospect of marrying a sick old man, especially since she was already in love with Charles Brandon. Apparently, Mary made her brother promise that if she should survive Louis XII, she could choose her second husband.

Mary’s marriage to King Louis XII of France did not last long. Louis XII died on January 1, 1515, just three months after the wedding. As he had no son, he was succeeded by his son-in-law François d’Angoulême from the House of Valois-Angoulême as King François I of France. Mary was aware that the new King of France would like her to marry a Frenchman to keep her dowry in France. However, she confided in François I that she wished to marry Charles Brandon and he agreed to help her. First, Mary had to follow the French royal custom of a widowed queen observing a 40-day mourning period. She spent the mourning period at the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris with darkened windows and candlelight. She was also observed to see if she was pregnant with the future heir to the throne.

Wedding portrait of Mary Tudor and Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, attributed to Jan Gossaert, circa 1515; Credit – Wikipedia

Henry VIII sent Charles Brandon to France to bring his sister back to England, and he made Brandon promise that he would not propose to Mary. Once in France, Brandon was persuaded by Mary to abandon this pledge. On March 3, 1515, Mary secretly married Charles Brandon at the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris in the presence of ten people including King François I of France. Technically, this was treason as Brandon had married a royal princess without the king’s consent. Mary and Brandon returned to England to face the wrath of her brother. Cardinal Thomas Wolsey managed to calm down King Henry VIII although some members of the Privy Council wanted Brandon imprisoned or executed. Over a period of time, Mary and Brandon had to pay a £24,000 fine, approximately £7,200,000 today. The fine was later reduced by Henry VIII. The couple was married again in the presence of King Henry VIII at the Grey Friar’s Church in Greenwich on May 13, 1515.

Charles Brandon and Mary spent most of their time at Westhorpe Hall in Suffolk, England. They also had a London residence, Suffolk Place. Brandon’s daughters from his marriage to Anne Browne, Lady Anne Brandon and Lady Mary Brandon, lived with them at Mary’s insistence.

Brandon and Mary had four two sons and two daughters but only their daughters survived childhood :

- Henry Brandon (1516 – 1522), died in childhood

- Lady Frances Brandon (1517 – 1559), married (1) Henry Grey, 3rd Marquess of Dorset, had three daughters including the ill-fated Lady Jane Grey (2) Adrian Stokes, had three children who all died in infancy

- Lady Eleanor Brandon (1519 – 1547), married Henry Clifford, 2nd Earl of Cumberland, two sons and one daughter, only the daughter survived childhood

- Henry Brandon, 1st Earl of Lincoln (c. 1523 – 1534), died in childhood

Mary opposed her brother’s attempt to obtain an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon so he could marry Anne Boleyn. Mary had known Catherine for many years and had a great fondness for her. She had developed a strong dislike for Anne Boleyn when Anne had served as one of her maids of honor in France.

Mary’s health began to suffer around the time King Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn married. There were rumors that the coronation of Anne Boleyn on June 1, 1533, broke Mary’s heart. She died at Westhorpe Hall on June 25, 1533, at the age of 37, and was originally buried in the Abbey at Bury St. Edmunds in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, England. In 1538, when the Abbey at Bury St. Edmunds was dissolved during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Mary’s coffin was brought to St. Mary’s Church in Bury St. Edmunds where it still rests in the crypt.

Katherine Willoughby, 12th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby, Duchess of Suffolk, drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger; Credit – Wikipedia

Less than two months after the death of Mary Tudor, Charles Brandon married again. His fourth and final wife was Katherine Willoughby, 12th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby. Katherine was the only child of William Willoughby, 11th Baron Willoughby de Eresby, and therefore was his heir. Her mother was Willoughby’s second wife María de Salinas, the Spanish-born lady-in-waiting to Catherine of Aragon. After her father’s death in 1526, seven-year-old Katherine became a ward of King Henry VIII. Two years later, Henry VIII sold the wardship, not an unusual occurrence, to Brandon. Katherine Willoughby grew up with Brandon’s children and it was common knowledge that the wealthy heiress would be betrothed to Brandon’s son Henry Brandon, 1st Earl of Lincoln. When Mary Tudor died, Katherine Willoughby was one of the chief mourners at her funeral. Not wanting to risk losing Katherine’s lands and wealth because his son Henry was too young to marry, Brandon married Katherine himself. Although at the time of their marriage, Brandon was forty-nine and Katherine only fourteen, the marriage was a successful one.

Miniature of Henry Brandon, 2nd Duke of Suffolk by Hans Holbein the Younger, circa 1541; Credit – Wikipedia

Charles Brandon and Katherine had two sons who both died on the same day of the sweating sickness, six years after their father’s death:

- Henry Brandon, 2nd Duke of Suffolk (1535 – 1551) died in his teens

- Charles Brandon, 3rd Duke of Suffolk (1537 – 1551) died in his teens an hour after his older brother

Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk was a military commander, was created a Knight of the Garter in 1513, and held several political positions during the reign of King Henry VIII:

- Earl Marshal 1524 – 1533

- Lord President of the Privy Council (1530 – 1545)

- Justice in Eyre (1534 – 1545)

- Lord Steward (1541 – 1544)

Throughout the reign of King Henry VIII, Charles Brandon remained close to the king, acting as a companion at court and often accompanying him on his travels. He accompanied Henry VIII to his famous 1520 summit with King François I of France known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold. In 1536, Brandon stood at the scaffold at the Tower of London, representing Henry VIII, at the execution of Anne Boleyn. Brandon led action against the 1536 – 1537 Pilgrimage of Grace, a protest against Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Henry VIII gave Brandon a large amount of church property that had been confiscated during the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Gravemarker of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk; Credit – Credit – https://www.stgeorges-windsor.org/charles-brandon-duke-of-suffolk/

During the summer of 1545, Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk was part of King Henry VIII’s entourage during a hunting progress. On August 24, 1545, Brandon, aged 60 – 61, died suddenly while the hunting progress was at Guildford Castle in Surrey, England. Henry VIII was grief-stricken at the loss of one of his oldest and most loyal friends. He arranged and paid for the burial of Brandon in the south quire aisle of St. George Chapel, Windsor Castle in Windsor, England. 18th-century historian Joseph Pote wrote regarding Brandon’s grave, “Nothing remains to distinguish the Grave of this noble Duke but a rude brick pavement.” Finally, in 1787, during the reign of King George III, it was “ordered that leave be given to lay a stone above the grave of Charles Brandon Duke of Suffolk, according to His Majesty’s directions”. The gravemarker was put in place by architect Henry Emlyn while conducting a restoration of St. George’s Chapel in 1787 – 1790 that included the repaving of the quire aisles and nave.

Miniature of Katherine Willoughby, 12th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby, Dowager Duchess of Suffolk by Hans Holbein the Younger; Credit – Wikipedia

After Charles Brandon’s death, his 26-year-old widow Katherine Willoughby, 12th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby, Dowager Duchess of Suffolk married Richard Bertie, a member of her household, out of love and shared religious beliefs. Katherine and Richard Bertie had one daughter and one son. Katharine survived her first husband Charles Brandon by thirty-five years, dying on September 19, 1580, aged 61, at her family home Grimsthorpe Castle in Lincolnshire, England which still remains in the Willoughby de Eresby family. Her son with Richard Bertie, Peregrine Bertie, inherited her title as the 13th Baron Willoughby de Eresby.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Charles Brandon, 1. Duke of Suffolk (2022) Wikipedia (German). Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Brandon,_1._Duke_of_Suffolk (Accessed: March 5, 2023).

- Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk (2023) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Brandon,_1st_Duke_of_Suffolk (Accessed: March 5, 2023).

- Cracknell, Eleanor. (2013) Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, College of St George. Available at: https://www.stgeorges-windsor.org/charles-brandon-duke-of-suffolk/ (Accessed: March 5, 2023).

- DeLisle, Leanda. (2013) Tudor – Passion, Manipulation, Murder. New York: PublicAffairs.

- Flantzer, Susan. (2016) Mary Tudor, Queen of France, Duchess of Suffolk, Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/mary-tudor-queen-of-france-duchess-of-suffolk/ (Accessed: March 5, 2023).

- Perry, Maria. (1998) The Sisters of Henry VIII. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Sir William Brandon, Kt. (2022) geni_family_tree. Available at: https://www.geni.com/people/Sir-William-Brandon-Kt/6000000006444764167 (Accessed: March 5, 2023).

- Weir, Alison. (2001) Henry VIII – The King and His Court. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.