by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2015

Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom; Credit – Wikipedia

Queen Victoria came to the British throne because of a great tragedy that struck the British Royal Family on November 6, 1817. Twenty-one-year-old Princess Charlotte of Wales, the only child of George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), died after delivering a stillborn son. At the time of her death, Charlotte, who was second in line to the throne, was the only legitimate grandchild of King George III, even though twelve of his fifteen children were still alive. If Charlotte had survived her grandfather King George III and her father, the future King George IV, she would have become Queen. Her death left no legitimate heir in the second generation and prompted the aging sons of King George III to begin a frantic search for brides to provide for the succession.

King George III’s eldest son (Charlotte’s father, the future King George IV) and his second son Frederick, Duke of York, were in loveless marriages, and their wives, both in their late forties, were not expected to produce heirs. The third son, William, Duke of Clarence (the future King William IV), age 53, married 26-year-old Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, while the fourth son, 50-year-old Edward, Duke of Kent, married 32-year-old widow Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafeld. Victoria was the sister of Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saafeld (the future King Leopold I of the Belgians), Princess Charlotte’s widower. Twenty-one-year-old Augusta of Hesse-Cassel married 44-year-old Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, the seventh son. It was then the scramble to produce an heir began.

Within a short time, the three new duchesses, along with Frederica, wife of the fifth son, Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, became pregnant. Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge gave birth to a son on March 26, 1819, and Adelaide, Duchess of Clarence had a daughter the following day. Victoria, Duchess of Kent produced a daughter on May 24, 1819, and three days later Frederica, Duchess of Cumberland had a boy. Adelaide’s daughter would have been the heir, but she died in infancy as did another daughter born the following year. The child of the next Royal Duke in seniority stood to inherit the throne. This was Alexandrina Victoria, daughter of Edward, Duke of Kent and Victoria. The baby was fifth in line to the throne after her father’s three elder brothers George, Frederick, and William, and her father Edward.

The baby’s father, Edward, died on January 23, 1820, eight months after her birth, and the infant princess was fourth in the line of succession. Six days later, King George III’s death brought his eldest son to the throne as George IV. Frederick, Duke of York, died in 1827, bringing the young princess a step closer to the throne. George IV died in 1830 and his brother William (IV) succeeded him. During William’s reign, little Drina, as she was called, was the heiress presumptive. There was always the possibility that King William IV and Queen Adelaide would still produce an heir, but it was not to be. King William IV died on June 20, 1837, and left the throne to his 18-year-old niece, who is known to history as Queen Victoria.

Queen Victoria was born at Kensington Palace in London, England on May 24, 1819. She was the only child of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. This was the second marriage for Victoria’s mother who was previously married to Emich Carl, 2nd Prince of Leiningen, and was widowed after 13 years of marriage. This marriage produced a half-brother and half-sister for Victoria:

Because Karl became the sovereign Prince of Leiningen at the age of ten, he lived in Leiningen (now in Germany), but Feodora lived in England with her mother and half-sister Victoria until her marriage in 1828. Victoria and Feodora had a close relationship and maintained a lifelong correspondence.

Victoria was christened a month after her birth at Kensington Palace and was given the names Alexandrina (after Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia, one of her godparents) and Victoria (after her mother). Efforts by her parents to use the names Georgina or Georgiana, Charlotte, and Augusta were thwarted by the Prince Regent (later King George IV). Her godparents were:

On January 23, 1820, Victoria’s father died of pneumonia six days before his father King George III died and less than a year after his daughter’s birth. After King George III’s death, the infant Victoria was third in the line of succession after her uncles, Frederick, Duke of York and William, Duke of Clarence. Neither the new king, George IV, nor his brothers Frederick and William had any legitimate heirs, and the Duchess of Kent decided she would take a chance on Victoria’s accession to the throne. The Duchess decided to stay in England rather than return to her homeland.

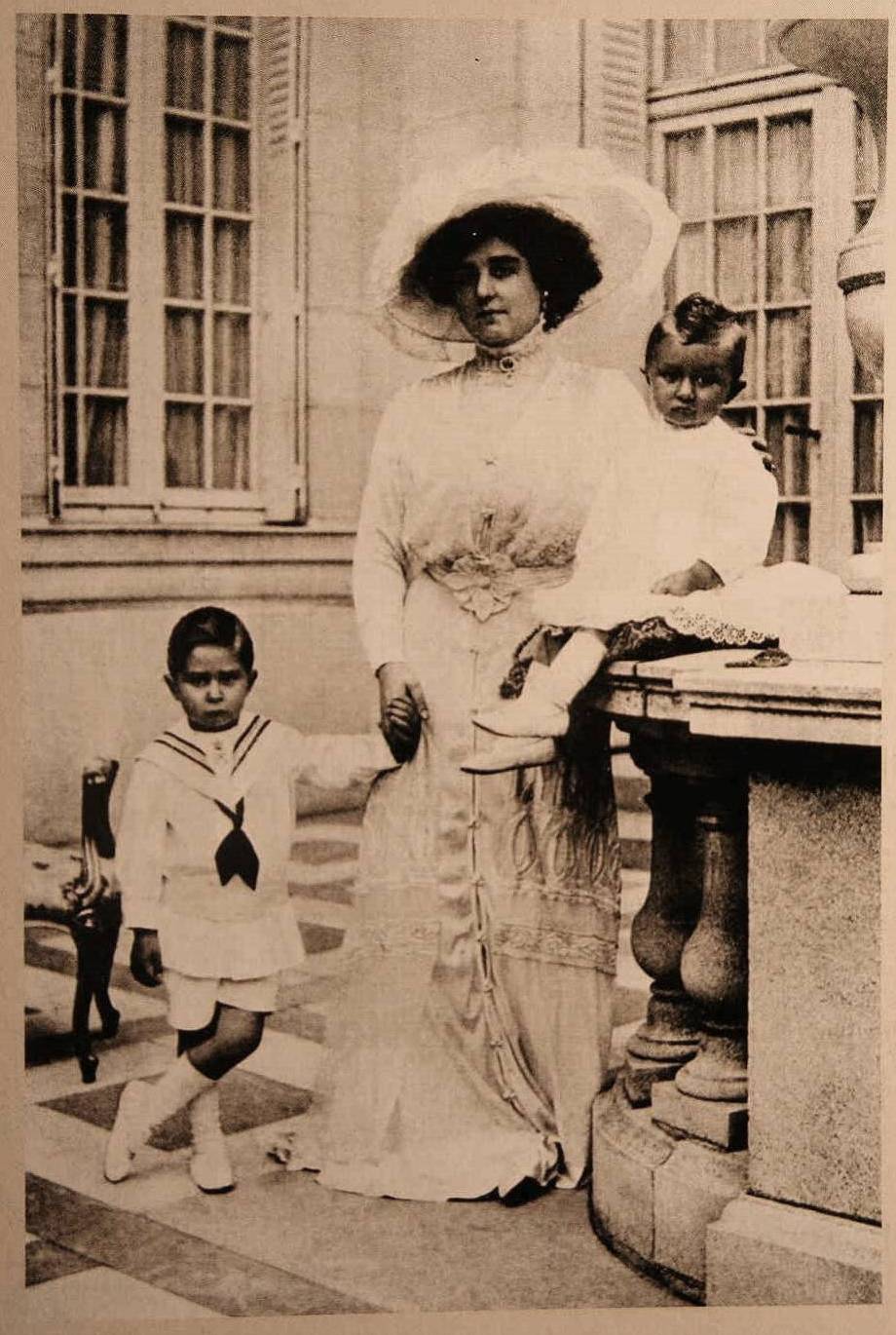

Duchess of Kent and Victoria; Credit – Wikipedia

The Duchess of Kent and her daughter Victoria were given little financial support from Parliament. The Duchess’ brother Leopold (the future King Leopold I of the Belgians) was the widower of Princess Charlotte and received a very generous 50,000 pounds per year income from Parliament upon his marriage to Charlotte which was continued after her death. Leopold provided much-needed financial and emotional support to his sister and niece. In 1831, with King George IV dead for a year and his younger brother and heir King William IV still without legitimate issue, Victoria’s status as heir presumptive and her mother’s prospective place as regent led to major increases in income. Uncle Leopold became King of the Belgians in 1831, so an additional consideration was the impropriety of a foreign monarch supporting the heir to the British throne. Leopold had surrendered his British income upon his accession to the Belgian throne.

There was no love lost between King William IV and his sister-in-law, the Duchess of Kent. Despite the Regency Act 1830 making the Duchess of Kent regent in case William died while Victoria was still a minor, the King distrusted the duchess’s capacity to be regent. In 1836 King William IV declared during a dinner in the Duchess’ presence that he wanted to live until Victoria’s 18th birthday so that a regency could be avoided.

Princess Victoria with her spaniel Dash, by George Hayter, 1833; Credit – Wikipedia

Victoria’s governess was Louise Lehzen, born to a Lutheran pastor in Hanover, Germany. Lehzen, as she was called, gave Victoria a very solid early education. When Victoria turned eight, she began to receive lessons from tutors in French, German, writing, mathematics, drawing, dancing, music, and singing. Shortly before, Victoria’s uncle William became king, Lehzen inserted a genealogical table in Victoria’s history book. Victoria carefully looked at it and said, “I see I am nearer to the throne than I thought,” and burst into tears. After she composed herself, Victoria said her famous remark, “I will be good.”

Lehzen was strongly protective of Victoria, who resided in a household dominated by the controlling Kensington System, implemented by the Duchess of Kent and her comptroller Sir John Conroy. Lehzen encouraged Victoria to become strong, informed, and independent from her mother’s and Conroy’s influence, causing friction between the two and Lehzen. Lehzen remained with Victoria until 1841 when she was quietly dismissed after Prince Albert, Victoria’s husband, had had enough of her jealousy and troublemaking. Lehzen was pensioned off to Hanover although Victoria and her former governess continued to correspond with each other.

On May 24, 1837, Victoria turned 18 years old and it would not be necessary for the Duchess of Kent to serve as regent, much to the relief of Victoria’s uncle King William IV. Less than a month later, on June 20, 1837, King William IV died and Victoria acceded to the British throne. On the day Victoria became queen, she demonstrated her determination to free herself from her mother’s influence by ordering her bed removed from the room she and her mother had always shared. Victoria’s coronation took place on June 28, 1838, at Westminster Abbey.

Even before Victoria became queen, the question of her eventual marriage had been discussed. Since 1836, Uncle Leopold had hoped to arrange a marriage between Victoria and his nephew (and Victoria’s first cousin) Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Leopold, Victoria’s mother, and Albert’s father Ernst I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha were all siblings. Victoria’s paternal uncle, King William IV, disapproved of a Coburg match and favored a marriage with Prince Alexander of the Netherlands, the second son of the future King Willem II of the Netherlands.

First cousins Victoria and Albert met for the first time in 1836 when Albert and his elder brother Ernst visited England. Seventeen-year-old Victoria seemed instantly infatuated with Albert. She wrote to her uncle Leopold, “How delighted I am with him, and how much I like him in every way. He possesses every quality that could be desired to make me perfectly happy.”

Prince Albert, 1839 lithography; Credit – Wikipedia

In October 1839, Albert and Ernst again visited England, staying at Windsor Castle with Victoria, who was now Queen. On October 15, 1839, the 20-year-old monarch summoned her cousin Albert and proposed to him. Albert accepted, but wrote to his stepmother, “My future position will have its dark sides, and the sky will not always be blue and unclouded.” The couple was married in the Chapel Royal at St. James’ Palace in London on February 10, 1840, at 1 p.m. Traditionally, royal weddings took place at night, but this wedding was held during the day so the Queen’s subjects could see the couple as they traveled down The Mall from Buckingham Palace.

Shortly after his marriage, Albert wrote to a friend, “I am only the husband and not the master in my house.” Albert was expected to be ready at a moment’s notice to go to his new wife to read aloud, play the piano, be petted, or blot her signature. Victoria was delighted to parade Albert before her court and, as she confided to her diary, to have him put her stockings on her feet.

During Victoria’s early pregnancies, Albert showed a talent for diplomatic dealings with her ministers and an ability to understand complex government documents. Soon Albert was dealing with more and more of Victoria’s governmental duties and they worked with their desks side by side. As Albert’s influence over Victoria grew, she began to defer to him on every issue.

Victoria was quite temperamental and had a strong sexuality which Albert apparently met, as evidenced by the birth of nine children. Albert was somewhat prudish and his high moral standards would never allow extramarital affairs. He found marriage to Victoria a full-time job which exhausted him physically and mentally. Victoria rewarded Albert by making him Prince Consort in 1857.

All of Victoria and Albert’s nine children grew to adulthood. However, their youngest son, Leopold, was afflicted with the genetic blood clotting disease hemophilia and two of their daughters, Alice and Beatrice, were hemophilia carriers.

Victoria and Albert’s nine children:

- Victoria, Princess Royal (1840-1901) married Friedrich III, German Emperor and King of Prussia, had four sons and four daughters

- King Edward VII of the United Kingdom (1841-1910) married Princess Alexandra of Denmark, had two sons and three daughters

- Princess Alice (1843-1878) married Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, had two sons and five daughters

- Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1844-1900) married Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna of Russia, had one son and four daughters

- Princess Helena (1846-1923) married Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, had two sons and two daughters

- Princess Louise (1848-1939) married John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne, 9th Duke of Argyll, no children

- Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught (1850-1942) married Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia, had one son and two daughters

- Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany (1853-1884) married Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont, had one son and one daughter

- Princess Beatrice (1857-1944) married Prince Henry of Battenberg, had three sons and one daughter

Victoria and Albert’s children and grandchildren married into other European royal families giving Victoria the unofficial title of “Grandmother of Europe.” Their grandchildren sat upon the thrones of Germany/Prussia, Greece, Norway, Romania, Russia, Spain, and the United Kingdom as monarchs or consorts. Through these marriages, Victoria and Albert’s daughters and granddaughters transmitted the genetic disease hemophilia to other royal families. Victoria and Albert’s descendants currently sit upon the thrones of Denmark, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Victoria and Albert with their nine children in 1857; Credit – Wikipedia

Victoria and Albert, whose primary residences were Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, felt they needed their own residences. Albert’s architectural talents are evident in the seaside Italian-style palace Osborne House on the Isle of Wight and Balmoral, a castle in the Scottish highlands. Osborne and Balmoral became Victoria’s favorite homes. Following Victoria’s death, Osborne was given to the state and served as a Royal Navy training college from 1903-1921. Today it is open to the public as a home of Queen Victoria. Balmoral Castle remains the private property of the monarch and is used by the British Royal Family for their summer holidays.

In December 1861, Albert, exhausted from dealing with a foreign policy issue and his eldest son’s affair with an actress, fell ill with a fever. Delirious and suffering from pain and chills, Albert died at Windsor Castle on December 14, 1861, at the age of 42. The cause of his death was diagnosed as typhoid fever, but modern medical experts speculate that he died from stomach cancer or some other debilitating disease.

Left a widow at 42, Victoria never fully recovered from her beloved Albert’s death. For the rest of her life, she wore only clothes of mourning black with a white widow’s cap on her head. Her handkerchiefs and stationery displayed wide black edges. In each of her homes, Albert’s room was kept as if he were still alive. Servants opened and closed the curtains, changed linens, and laid out Albert’s clothes. Victoria slept with his nightshirt for years. Most notable was her almost complete withdrawal from public life for the rest of her reign. She did find some comfort in her ever-growing family of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Eventually, Victoria made trips to the south of France, where she enjoyed the Mediterranean sunshine.

During her widowhood, two servants became important to Victoria, much to the distress of her family. During her early widowhood, Victoria relied heavily on her Scottish Highland servant John Brown from Balmoral. There were rumors of a romance and a secret marriage, and Victoria was called Mrs. Brown. Brown treated the queen in a rough and familiar but kind manner, which she relished. In return, Brown was allowed many privileges which infuriated Victoria’s family.

Queen Victoria and John Brown at Balmoral in 1863; Credit – Wikipedia

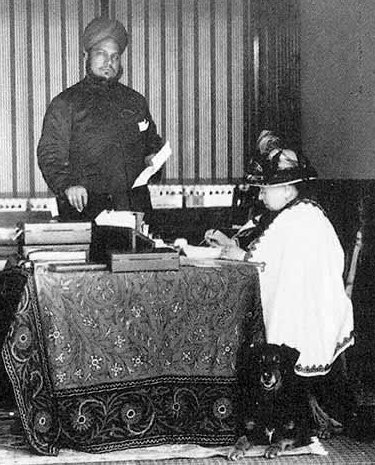

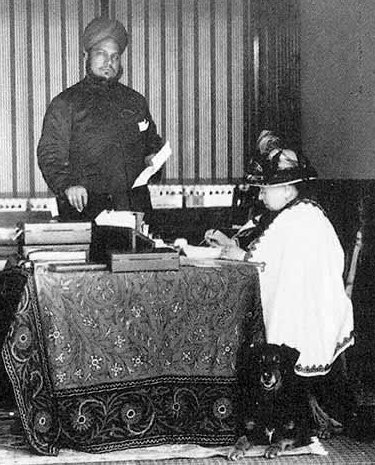

After John Brown died in 1883, Queen Victoria became similarly attached to an Indian Muslim servant Abdul Karim, called the Munshi, who began working for her in 1887. The Munshi was resented even more than John Brown had been. At least John Brown’s loyalty to Queen Victoria was without question, but there was evidence that the Munshi exploited his position for personal gain and prestige. The Munshi remained with Victoria until her death when he was dismissed and sent back to India by Victoria’s son and successor King Edward VII.

The Munshi and Queen Victoria in 1897; Credit – Wikipedia

On January 1, 1877, Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India. This was a great source of pride and satisfaction to Victoria because now she was on an equal status with Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria, Emperor Alexander II of Russia, and Wilhelm I, German Emperor as she considered herself greatly superior to all of them.

In 1887, Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee marking 50 years on the throne, and ten years later she celebrated her Diamond Jubilee marking her 60th year as queen. On September 23, 1896, Victoria surpassed her grandfather King George III as the longest-reigning British monarch. On September 9, 2015, her great-great-granddaughter Queen Elizabeth II surpassed Queen Victoria as the longest-reigning British monarch.

Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee photo; Credit – Wikipedia

By the time Queen Victoria was in the last year of her life, she had lost three of her nine children. Princess Alice died on December 14, 1878, the 17th anniversary of Prince Albert’s death, at the age of 35 from diphtheria. Prince Leopold, who suffered from hemophilia, died at the age of 30 on March 28, 1884, from a cerebral hemorrhage following a fall. Lastly, Prince Alfred, aged 55, died of throat cancer, on July 30, 1900. Victoria, Princess Royal was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1899 and then spine cancer in 1900. She died on August 5, 1901, less than seven months after her mother’s death. Two of Victoria’s children, Princess Louise and Prince Arthur, lived to be 91. Victoria’s youngest child Princess Beatrice outlived all her siblings. She died at the age of 87 in 1944 and the 18-year-old Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen Elizabeth II, attended her funeral.

Queen Victoria had enjoyed good health throughout her life but in the last year of her life, she suffered from indigestion, insomnia, weight loss, and some difficulty with speaking, reading, and writing. Rheumatism made it difficult to walk and cataracts made it difficult to see. On December 18, 1900, she traveled to Osborne House on the Isle of Wight for the last time. The journey exhausted her, but after a few days, she seemed somewhat recovered. However, by January 16, 1901, it was obvious that Queen Victoria’s life was drawing to an end. She died at Osborne House on January 22, 1901, surrounded by her family. Her funeral was held at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, and she was interred beside Prince Albert in the Frogmore Mausoleum in Windsor Great Park.

Sarcophagus of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore. Credit: www.findagrave.com

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

House of Hanover and Queen Victoria Resources at Unofficial Royalty