by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2023

The Coronation Chair; Credit – By Darkmaterial – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=127657004

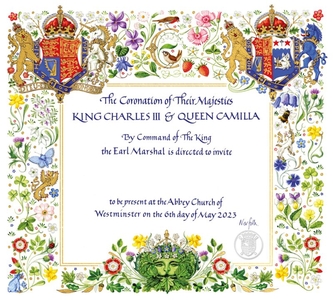

On May 6, 2023, King Charles III will become the 41st English/British reigning monarch to be crowned since the coronation of King William I on December 25, 1066. There have been forty coronation ceremonies for sovereigns since December 25, 1066. Co-rulers, husband and wife, and first cousins, King William III and Queen Mary II, were crowned at the same coronation ceremony.

Resources about coronations from the Westminster Abbey website and the Official Website of the British Monarchy:

Check out all our British coronation articles at the link below:

The Coronation Stone in Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, England; Credit – By Hellodavey1902 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=94084918

The coronation of the English/British monarch has its roots in the Kings of Wessex and the early Anglo-Saxon Kings of the English being installed on the Kings’ Stone or Coronation Stone which can still be seen in Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, England. For the coronation of Edgar the Peaceful, King of the English in 973, Saint Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury felt there was a need for a major ceremony similar to the coronations of the King of the Franks and the German Emperor. Although Edgar probably had a ceremony at Kingston-on-Thames, a coronation using Dunstan’s order of service was held for Edgar at Bath Abbey in Bath, England on May 11, 973. Since then, the main elements of the British coronation service and the form of the oath taken by the sovereign can be traced to the order of service devised by Saint Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury.

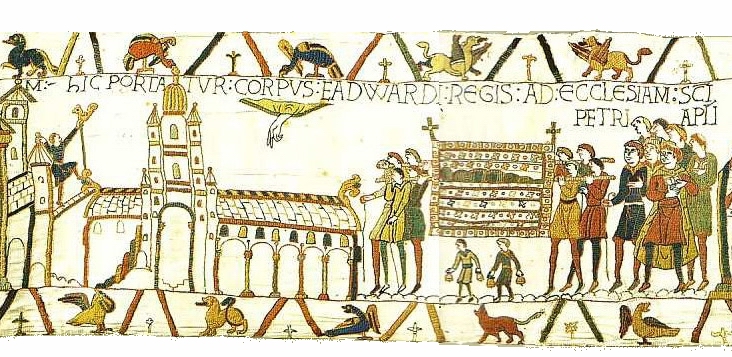

The first documented coronation at Westminster Abbey in London, England was that of Harold II Godwinson, King of England on January 6, 1066. The last crowned king from the House of Wessex, Harold would lose his crown and his life on October 14, 1066, at the Battle of Hastings when he was defeated by William II, Duke of Normandy. Edgar the Ætheling, the last male of the Anglo-Saxon House of Wessex, was the nominal King of England for about six weeks. As the position of William II, Duke of Normandy grew stronger, it became evident to those in power that Edgar the Ætheling should be abandoned in favor of William who became King William I of England, also known as William the Conqueror. On Christmas Day 1066, William was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey.

Upon the death of the sovereign, there is an immediate transference of power. The heir to the throne becomes the new sovereign immediately upon his/her predecessor’s death. “The king is dead, long live the king!” If the sovereign is a male and is married, his wife instantly becomes the queen consort (the wife of a reigning king). A coronation is not necessary at all for a person to become the sovereign or the queen consort.

King Edward V, one of the “Princes in the Tower,” two disputed monarchs Empress Matilda, Lady of the English, the only surviving child of King Henry I, and Lady Jane Grey, and additionally King Edward VIII who abdicated in 1936, are the only monarchs since the Norman Conquest in 1066 who were never crowned.

A number of queen consorts were not crowned with their husbands but were crowned in a separate ceremony. The reasons vary from not being married when their husbands became king, not being in England at the time, pregnancy, and illness. Eight queen consorts were never crowned. Margaret of France, the second wife of King Edward I, was never crowned, making her the first queen consort since the Norman Conquest in 1066 not to be crowned. King Henry VIII apparently did not feel the need to have his last four wives crowned. Three of them were queens for a short time: Jane Seymour (15 months, died), Anne of Cleves (7 months, divorced), Catherine Howard (16 months, beheaded). Henry VIII’s last wife Catherine Parr (survived) was queen for a bit longer, 2 ½ years. Henrietta Maria of France, wife of King Charles I, and Catherine of Braganza, wife of King Charles II, were not crowned because they were Roman Catholic and did not want to participate in a Church of England ceremony. King George IV’s estranged wife Caroline of Brunswick was prevented from being crowned with him. When she showed up at Westminster Abbey on the day of the coronation, she was turned away.

********************

Below is some basic information about each coronation along with some succession and coronation details and some interesting stories.

Unless otherwise noted, all pictures, portraits, and photos are from Wikipedia.

********************

Coronations after the Norman Conquest (1066 – present)

King William I of England

- Child of Robert I the Magnificent, Duke of Normandy and his mistress Herleva of Falaise

- Born: circa 1028

- House of Normandy

- Accession Date: December 25, 1066

- Coronation: December 25, 1066 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Ealdred, Archbishop of York

- Spouse: Matilda of Flanders, Queen of England, crowned May 11, 1068, at Westminster Abbey by Ealdred, Archbishop of York

- Death: September 8, 1087

- Unofficial Royalty: King William I of England (the Conqueror)

William I wanted to await the arrival of his wife in England before he was crowned but because he gained the throne by conquest, he felt an urgency to have his coronation sooner rather than later. At the coronation, Ealdred, Archbishop of York presented the king to the people, speaking in English and then Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances, a trusted advisor of William I, spoke the same words in French. When the congregation shouted their approval, the soldiers standing guard outside thought the noise inside was an assassination attempt and began setting fire to houses around Westminster Abbey. Smoke filled the Abbey, the congregation fled, and riots broke out. However, King William I, Ealdred, Archbishop of York, and Geoffrey, Bishop of Coutances completed the service despite the chaos.

********************

King William II Rufus of England

King William I divided his lands, the Duchy of Normandy and the Kingdom of England, between his two eldest surviving sons. Robert Curthose, the eldest, received the Duchy of Normandy and the second son William Rufus received the Kingdom of England. Very little is known about William II Rufus’s coronation other than Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury was the officiant and the Anglo-Saxon order of service was used.

********************

King Henry I of England

- Child of King William I of England and Matilda of Flanders

- Born: circa 1068

- House of Normandy

- Accession Date: August 2, 1100

- Coronation: August 5, 1100 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Maurice, Bishop of London

- Spouse: (1) Matilda of Scotland, Queen of England, crowned November 11, 1100 at Westminster Abbey by Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury (2) Adeliza of Louvain, Queen of England, crowned February 3, 1122 at Westminster Abbey by Ralph d’Escures, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: December 1, 1135

- Unofficial Royalty: King Henry I of England

On August 2, 1100, King William II Rufus rode out from Winchester Castle on a hunting expedition to the New Forest, accompanied by his brother Henry and several nobles. During the hunt, an arrow hit William Rufus in his chest, puncturing his lungs, and killing him. It has long been argued that his death was an assassination plot by his brother Henry. Henry’s two older brothers, King William II Rufus of England and Robert Curthose III, Duke of Normandy, who had been given the Duchy of Normandy by their father, had made a pact stating that if one of them died without heirs, both Normandy and England would be reunited under the surviving brother. However, at the time of William Rufus’ death, Robert Curthose was in the Holy Land on a Crusade so Henry was able to seize the crown of England for himself. Henry hurried to Winchester to secure the royal treasury. The day after William’s funeral at Winchester, the nobles acclaimed Henry as king. King Henry I then left for London where he was crowned three days after William’s death by Maurice, Bishop of London because there was no Archbishop of Canterbury at that time.

********************

King Stephen of England

- Child of Stephen II, Count of Blois and Adela of Normandy and England, daughter of King William I of England

- Born: 1092 or 1096

- House of Blois

- Accession Date: December 1, 1135

- Coronation: December 22, 1135 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: William de Corbeil, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Matilda of Boulogne, Queen of England, crowned March 22, 1136 at Westminster Abbey by William de Corbeil, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: October 25, 1154

- Unofficial Royalty: King Stephen of England

On November 25, 1120, during the reign of King Henry I, a terrible tragedy caused a succession crisis in England. The White Ship carrying King Henry I’s only legitimate son William Ætheling, sank as it left France to sail to England, and William Ætheling drowned. Empress Matilda was Henry I’s only surviving legitimate child and on Christmas Day of 1126, Henry I made his barons swear to recognize Empress Matilda and any future legitimate heirs she might have as his successors.

On December 1, 1135, King Henry I of England died. His nephew Stephen of Blois, the son of Henry I’s sister Adela of Normandy and England, quickly crossed the English Channel from Boulogne (now in France) to England, accompanied by his military household. With the help of his brother Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester, Stephen seized power in England. William de Corbeil, Archbishop of Canterbury was persuaded to crown Stephen. It was argued that the oath King Henry I made his barons swear in support of his daughter Matilda was invalid as it had been exacted by force. A fictitious story that King Henry I had changed his mind about the succession on his deathbed was also circulated.

Empress Matilda did not give up her claim to England and Normandy, leading to the long civil war known as The Anarchy between 1135 and 1153. Shortly after the death of Stephen’s only son in 1153, Stephen and Henry FitzEmpress, Empress Matilda’s son, reached a formal agreement that allowed Stephen to keep the throne until his death but forced him to recognize Empress Matilda’s son Henry FitzEmpress, as his heir.

********************

King Henry II of England

- Child of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine and Empress Matilda, Lady of the English, the only surviving child of King Henry I

- Born: March 5, 1133

- House of Angevin

- Accession Date: October 25, 1154

- Coronation: December 19, 1154 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Theobald of Bec, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine (in her own right), Queen of England, crowned with her husband

- Death: July 6, 1189

- Unofficial Royalty: King Henry II of England

With the accession of King Henry II, England had its first undisputed king for over a century. Traveling from his French possessions (Henry was also Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, and Count of Nantes and his wife Eleanor was Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right.), Henry II arrived in England on December 8, 1154. He immediately took the oaths of loyalty from the barons, Eleven days later, Henry and his very pregnant wife Eleanor were crowned at Westminster Abbey.

********************

King Richard I of England

- Child of King Henry II of England and Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine

- Born: September 8, 1157

- House of Angevin

- Accession Date: July 6, 1189

- Coronation: September 3, 1189 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Berengaria of Navarre, Queen of England, crowned May 12, 1191 at the Chapel of St. George in Limassol, Cyprus by Jean FitzLuke, Bishop of Evreux

- Death: April 6, 1199

- Unofficial Royalty: King Richard I of England

Richard I’s coronation is the first coronation that has a detailed account by a chronicler, Roger of Hoveden. His account, in which Richard is referred to as Duke of Normandy, can be read at the link below. On the day of his coronation, Richard proceeded to Westminster Abbey from the nearby Palace of Westminster followed by a crowd of nobles, clergy, and people. After the oath and anointing Richard took the crown from the altar and handed it to the Archbishop of Canterbury who then crowned him. After the coronation service, Richard changed to a lighter crown for the banquet which followed in Westminster Hall. On May 12, 1191, on his way to a Crusade in the Holy Land, Richard married Berengaria of Navarre at the Chapel of St. George in Limassol, Cyprus. Berengaria was crowned as part of the marriage ceremony. Then Richard, his new wife Berengaria, and his recently widowed sister Joan, Queen of Sicily accompanied Richard throughout the Crusade.

********************

King John of England

- Child of King Henry II of England and Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine

- Born: December 24, 1166

- House of Angevin

- Accession Date: April 6, 1199

- Coronation: May 27, 1199 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: (1) Isabella, 3rd Countess of Gloucester, marriage annulled (2) Isabella, Countess of Angoulême, Queen of England, crowned October 8, 1200 at Westminster Abbey by Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: October 19, 1216

- Unofficial Royalty: King John of England

John succeeded his childless elder brother Richard I who died of gangrene from an arrow wound. Arthur of Brittany, the son of John’s deceased elder brother Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany, had a better claim to the throne based upon the laws of primogeniture. However, Richard reportedly chose John as his successor on his deathbed. John acted promptly, seizing the royal treasury at Château de Chinon, a stronghold of the House of Angevin, in the Duchy of Anjou, now in France. On April 25, 1199, John was invested as Duke of Normandy in Rouen, the capital. He then left for England and his coronation was held at Westminster Abbey on May 27, 1199. During his coronation, John displayed “unseemly levity” and left before receiving Holy Communion.

********************

King Henry III of England

The second coronation of King Henry III

- Child of King John of England and his second wife Isabella, Countess of Angoulême

- Born: October 1, 1207

- House of Plantagenet

- Accession Date: October 19, 1216

- Coronation: (1) October 28, 1216 at Gloucester Cathedral (2) May 17, 1220 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: (1) Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester (2) Cardinal Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Eleanor of Provence, Queen of England, crowned January 20, 1236 at Westminster Abbey by Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: November 16, 1272

- Unofficial Royalty: King Henry III of England

King John died on October 18, 1216, leaving Henry, his nine-year-old son, to inherit his throne in the midst of the First Barons’ War (1215 – 1217), in which a group of rebellious barons supported by a French army, made war on King John because of his refusal to accept and abide by the Magna Carta. Because a large part of eastern England was under the control of the rebellious barons and the French, it was thought that the young King Henry III should be crowned as soon as possible to reinforce his claim to the throne. Therefore, Henry III was crowned on October 28, 2016, at Gloucester Cathedral with a golden circlet belonging to his mother as the coronation regalia were at Westminster in London. On May 20, 1220, King Henry III was crowned a second time in Westminster Abbey with a full coronation ceremony.

********************

King Edward I of England

In 1270, Edward had gone off on the Crusades accompanied by his wife Eleanor of Castile, and at the time of his father’s death in 1272, he was in Sicily making his slow way back to England. The new King Edward I thought England was safe under his mother’s regency and a royal council led by Robert Burnell, so he did not hurry back to England. On his way back to England, King Edward I visited Pope Gregory X in Rome and King Philip III of France in Paris and suppressed a rebellion in Gascony. He finally arrived back in his kingdom on August 2, 1274. On August 19, 1274, King Edward I and his wife Eleanor were crowned at Westminster Abbey. After Robert Kilwardby, Archbishop of Canterbury placed the crown on his head, King Edward I then removed the crown declaring he would not wear it again until he had recovered lands his father had lost during his reign. During his reign, King John had Normandy, Maine, Touraine, Anjou, and Poitou, all French ancestral territories of his Norman or Angevin ancestors. King Edward I was not successful in recovering the territories.

The Coronation Chair with Stone of Scone in Westminster Abbey, 1885

King Edward I’s relentless, but unsuccessful campaign to assert his overlordship over Scotland was resisted by William Wallace and Robert the Bruce, (later King Robert I of Scotland) but it gave him one of his nicknames, “Hammer of the Scots.” In 1296, Edward I captured the Stone of Scone, an oblong block of red sandstone that was used for centuries in the coronation of the monarchs of Scotland. It was kept at the now-ruined Scone Abbey in Scone, near Perth, Scotland. Edward took the Stone of Scone back to England and placed it in the care of the Abbot of Westminster Abbey.

An oaken chair, called the Coronation Chair, King Edward’s Chair, or St. Edward’s Chair, was made by order of King Edward I to enclose the Stone of Scone. Originally the chair was painted with images of birds, foliage, and animals on a gilt ground. The figure of a king, either Edward the Confessor or King Edward I, his feet resting on a lion, was painted on the back. The four gilt lions on the legs were made in 1727 to replace the original lions which were not added to the chair until the early 16th century. The chair has been in use at coronations since 1308 although opinion is divided as to when it was actually used for the crowning. However, since the coronation of King Henry IV in 1399, the monarch has been crowned in the chair. Originally the Coronation Chair was kept in St. Edward’s Chapel at Westminster Abbey, the site of the shrine of St. Edward the Confessor. The Coronation Chair is now kept in a specially-built enclosure in St. George’s Chapel at the west end of the nave, near the main doors of Westminster Abbey.

In 1996, 700 years after it was taken, the Stone of Scone was returned to Scotland. It is kept at Edinburgh Castle in the Crown Room alongside the crown jewels of Scotland (the Honours of Scotland). An agreement was made that the Stone of Scone will be returned to Westminster Abbey and placed in the Coronation Chair for future coronations, and then it will be returned to Edinburgh Castle. This writer has been fortunate to see the Stone of Scone both at Westminster Abbey and Edinburgh Castle.

********************

King Edward II of England

King Edward II decided to delay his coronation until after his marriage. After he married Isabella of France on January 25, 1308, at Boulogne Cathedral in France, the newlyweds returned to England in February, where Edward II ordered Westminster Palace to be lavishly decorated for their coronation celebrations. Henry Woodlock, Bishop of Winchester was the officiant at the coronation, organized by Piers Gaveston, Edward II’s favorite. Woodlock had received a special commission from the exiled Robert Winchelsey, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was an opponent of King Edward II. English and French nobles attended the magnificent ceremony and the celebrations which followed. However, the celebrations were disrupted by the large crowds of eager spectators who surged into the palace, knocking down a wall, and forcing Edward II to flee for his safety.

********************

King Edward III of England

Edward III’s father King Edward II was a weak king and his relationship with his favorites Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger, whether they were friends, lovers, or sworn brothers, was problematic and caused discontent both among the nobles and the royal family. Opposition to the regime grew, and when Edward II’s wife Isabella was sent to France to negotiate a peace treaty in 1325, she turned against Edward and refused to return. Isabella allied herself with the exiled Roger Mortimer, 3rd Baron Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, and invaded England with a small army in 1326. Edward II died in Berkeley Castle on September 21, 1327, probably murdered on the orders of Isabella and Mortimer.

Edward II’s 14-year-old son Edward was proclaimed Keeper of the Realm in October 1326 and then King Edward III of England in January 1327 when his father was forced to abdicate. Edward III’s mother Isabella and Roger Mortimer, 3rd Baron Mortimer, 1st Earl of March acted as regents for the young king. Due to a concern to confirm the legitimacy of King Edward III’s rule, the coronation was quickly organized, and King Edward III was crowned in Westminster Abbey on February 1, 1327.

********************

King Richard II of England

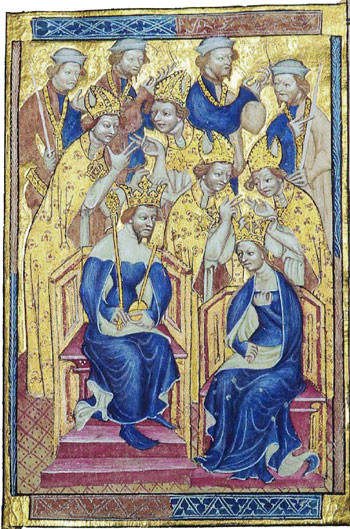

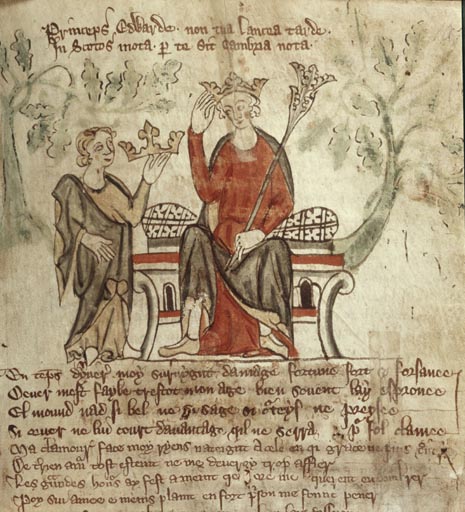

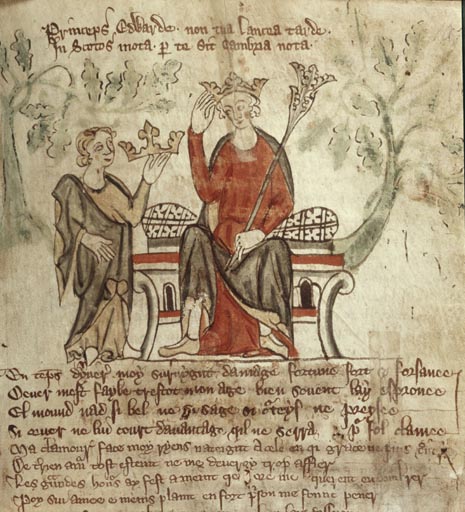

Coronation of King Richard II

- Child of Edward, Prince of Wales (also known as The Black Prince), eldest son and heir of King Edward III of England, predeceased his father, and Joan of Kent, 4th Countess of Kent

- Born: January 6, 1367

- House of Plantagenet

- Accession Date: June 21, 1377

- Coronation: July 16, 1377 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: (1) Anne of Bohemia, Queen of England, crowned January 22, 1382 at Westminster Abbey by William Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury (2) Isabella of Valois, Queen of England, crowned January 8, 1397 at Westminster Abbey by Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Richard was forced to abdicate the crown in 1399 to his first cousin Henry Bolingbroke who became King Henry IV, the first king of the House of Lancaster

- Death: Richard was imprisoned at Pontefract Castle in Yorkshire where he died on or around February 14, 1400.

- Unofficial Royalty: King Richard II of England

Richard’s father Edward III’s eldest son and heir, Edward, Prince of Wales, who has come to be known as the Black Prince, died at the age of 45, probably of dysentery, in 1376, a year before his father died, and his 10-year-old son succeeded his grandfather as King Richard II.

Richard’s coronation took place on July 16, 1377, at Westminster Abbey, just eleven days after his grandfather’s funeral. The quickness with which all this happened was certainly affected by the controversial succession of a child king whose father had not been the king. The day before his coronation, the young King Richard II rode on horseback from the Tower of London to the Palace of Westminster. The streets were filled with entertainers and decorated with bright banners and tapestries. This was the first-ever coronation procession.

In 1398, Henry Bolingbroke, first cousin of King Richard II and the eldest child of King Edward III’s third son John of Gaunt, quarreled with Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk, who accused him of treason. The two men planned to duel, but instead, King Richard II banished them from England, and Henry went to France. John of Gaunt died on February 3, 1399, and Richard II confiscated the estates of his uncle and stipulated that Henry would have to ask him to restore the estates. Henry returned to England while his cousin Richard was on a military campaign in Ireland and began a military campaign of his own, confiscating the land of those who had opposed him. King Richard II eventually was abandoned by his supporters and was forced by Parliament on September 29, 1399, to abdicate the crown to his cousin who reigned as King Henry IV, the first king of the House of Lancaster. Richard II was imprisoned at Pontefract Castle in Yorkshire where he died on or around February 14, 1400. The exact cause of his death, thought to have been starvation, is unknown.

********************

King Henry IV of England

- Child of John of Gaunt, son of King Edward III of England, and his first wife Blanche of Lancaster, Duchess of Lancaster

- Born: April 15, 1367

- House of Lancaster

- Accession Date: September 30, 1399

- Coronation: October 13, 1399 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: (1) Mary de Bohun, Countess of Northampton, Countess of Derby, died before Henry became king (2) Joan of Navarre, Queen of England, crowned February 26, 1403 at Westminster Abbey by Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: March 20, 1413

- Unofficial Royalty: King Henry IV of England

Coronation of King Henry IV

Henry IV’s coronation was held just two weeks after his accession, on a symbolic date, October 13, the feast day of St. Edward the Confessor, King of England. Because he had usurped the throne, Henry IV’s coronation was a means to establish his authority and demonstrate that he was a king for all the English people. First, there was a grand procession from the Tower of London with Henry IV dressed in royal blue and cloth of gold on a white horse, surrounded by 2,000 lords, ladies, knights, and members of his household. Henry IV entered Westminster Abbey under a golden canopy while his heir, thirteen-year-old Prince Henry, the future King Henry V, walked next to his father, carrying the Coronation sword. Prince Henry was created Prince of Wales at his father’s coronation.

Below is a link to an account of King Henry IV’s coronation from Froissart’s Chronicles, a history of the Hundred Years’ War written in the 14th century by Jean Froissart.

********************

King Henry V of England

- Child of King Henry IV of England and his first wife Mary de Bohun, Countess of Northampton, Countess of Derby

- Born: September 16, 1386

- House of Lancaster

- Accession Date: March 20, 1413

- Coronation: April 9, 1413 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Catherine of Valois, Queen of England, crowned February 23, 1421 at Westminster Abbey by Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: August 31, 1422

- Unofficial Royalty: King Henry V of England

On the day of King Henry V’s coronation, there was a terrible snowstorm, but people were undecided as to whether it was a good or bad omen. The procession from the Tower of London was slow due to the snow and had to be stopped periodically to shake the snow from the canopy held over Henry V’s head. Henry V dropped something on the floor during the coronation. The service was stopped so that Henry and those near him could search for the object. Because the coronation was held during Lent, all the dishes served at the coronation banquet were fish rather than meat.

On June 2, 1420, King Henry V married Catherine of Valois. Catherine went to England with Henry and was crowned in Westminster Abbey on February 23, 1421. In June 1421, Henry returned to France to continue his military campaigns. Catherine was already several months pregnant and gave birth to a son, the future King Henry VI, on December 6, 1421. King Henry V never saw his son. The warrior king, the victor against the French at the Battle of Agincourt, determined to conquer France once and for all, succumbed to dysentery, a disease that killed more soldiers than battle, on August 31, 1422, at the age of 35, leaving a nine-month-old son to inherit his throne.

********************

King Henry VI of England

The accession of the baby King Henry VI

- Child of King Henry V of England and Catherine of Valois

- Born: December 6, 1421

- House of Lancaster

- Reigned: August 31, 1422 – March 4, 1461 and October 3, 1470 – April 11, 1471

- Coronation: November 6, 1429 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England, crowned May 30, 1445 at Westminster Abbey by John Stafford, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: Deposed April 11, 1471, died on May 21, 1471, probably murdered on orders from King Edward IV

- Unofficial Royalty: King Henry VI of England

The baby King Henry VI seated in his mother’s lap, presided over Parliament on September 28, 1423, when the nobles swore loyalty to him. One of Henry V’s surviving brothers, John, Duke of Bedford, was appointed Regent, and Henry V’s other surviving brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, was appointed Protector and Defender of the Realm. Henry VI’s coronation was postponed until he was a month short of being eight years old.

Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou married in 1445 and had one child, Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales. Shortly before his son was born, Henry VI had some kind of mental breakdown. He was unable to recognize or respond to people for over a year. During Henry’s incapacity, Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, the next in line to the throne after Henry’s son, governed as Lord Protector. Even before the birth of Henry’s son, factions were forming and the seeds of the Wars of the Roses, the battle for the English throne between the House of Lancaster and the House of York, were being planted.

There was a give and take of power between the two royal houses as can be seen from the dates of the reigns of King Henry VI from the House of Lancaster and King Edward IV of the House of York, the son of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York who was killed at the 1460 Battle of Wakefield. Eventually, King Edward IV permanently got the upper hand. The final decisive Yorkist victory was at the Battle of Tewkesbury on May 4, 1471, when Henry VI’s only child Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales was killed. Henry VI was sent to the Tower of London and died on May 21, 1471, probably murdered on orders from King Edward IV.

********************

King Edward IV of England

- Child of Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York and Cecily Neville, both great-grandchildren of King Edward III of England

- Born: April 28, 1442

- House of York

- Reigned: March 4, 1461 – October 3, 1470 and April 11, 1471 – April 9, 1483

- Coronation: June 28, 1461 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Cardinal Thomas Bouchier, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England, crowned May 26, 1465 at Westminster Abbey by Cardinal Thomas Bouchier, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: April 9, 1483

- Unofficial Royalty: King Edward IV of England

King Edward IV was not crowned until his second reign due to the unstable nature of the throne because of the ongoing Wars of the Roses. On June 26, 1461, Edward IV went to the Tower of London as it was customary to stay there a night before the coronation. There he created twenty-eight new Knights of the Bath, including his brothers 12-year-old George and 8-year-old Richard, the future King Richard III. The next day, Edward was escorted by the new Knights of the Bath, all in blue gowns with white hoods, in a procession to the Palace of Westminster where Edward would spend the night before his coronation.

Edward was crowned King of England on Sunday morning, June 28, 1461, by Thomas Bourchier, Archbishop of Canterbury who was assisted by William Booth, the Archbishop of York. After the coronation, a banquet was held in Westminster Hall with King Edward IV sitting under a canopy of cloth of gold.

********************

King Edward V of England

On April 9, 1483, King Edward IV died and he was succeeded by his 12-year-old son as King Edward V. King Edward IV had named his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester as his son’s Lord Protector. The Duke of Gloucester had his nephew brought to the Tower of London on May 19, 1483, to await his coronation, which never happened. Edward V’s mother was persuaded to let her second son Richard, Duke of York join his brother, who was lonely, at the Tower of London. Richard joined his brother on June 16, 1483.

On June 22, 1483, a sermon was preached at St. Paul’s Cross in London declaring King Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville invalid and his children illegitimate and ineligible for the throne. This information apparently came from Robert Stillington, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, who claimed Edward IV had a legal pre-contract of marriage to Eleanor Butler, invalidating his later marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. King Edward IV’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester assumed the throne as King Richard III. The Titulus Regius, enacted by Parliament in 1484 officially declared Edward IV’s children illegitimate.

Edward and his brother Richard were seen less and less until the end of the summer of 1483 when they disappeared from public view altogether. Their fate is unknown and remains one of history’s greatest mysteries. There are a number of theories, and the most plausible lay blame on their uncle King Richard III, Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, or King Henry VII.

********************

King Richard III of England

- Child of Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York and Cecily Neville, both great-grandchildren of King Edward III of England

- Born: October 2, 1452

- House of York

- Accession Date: June 26, 1483

- Coronation: July 6, 1483 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Cardinal Thomas Bouchier, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Anne Neville, Queen of England, crowned with her husband

- Death: August 22, 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth Field, defeated in battle by Henry Tudor, the Lancastrian leader, who became the first monarch of the House of Tudor, King Henry VII

- Unofficial Royalty: King Richard III of England

King Richard III’s coronation occurred on July 6, 1483, just ten days after his accession. The day before the coronation, Richard and his wife Anne Neville rode in procession from the Tower of London to the Palace of Westminster. On their coronation day, King Richard III and Queen Anne walked barefoot on a red carpet to Westminster Abbey. Queen Anne’s train was carried by Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby whose son would become King Henry VII after defeating Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Almost the entire peerage of England witnessed the coronation which was followed by the traditional coronation banquet in Westminster Hall.

********************

King Henry VII of England

- Child of Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond and Lady Margaret Beaufort, a descendant of King Edward III. Lady Margaret’s grandfather John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset was the eldest child of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, son of King Edward III, and his mistress Katherine Swynford, whom he married in 1396. Their children were declared legitimate by King Richard II of England and Pope Boniface IX.

- Born: January 28, 1457

- House of Tudor

- Accession Date: August 22, 1485

- Coronation: October 30, 1485 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Cardinal Thomas Bouchier, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Elizabeth of York, Queen of England, daughter of King Edward IV, crowned November 25, 1487 at Westminster Abbey by Cardinal John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Death: April 21, 1509

- Unofficial Royalty: King Henry VII of England

Henry Tudor’s mother Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, a descendant of King Edward III, actively promoted her son as an alternative to King Richard III. King Edward IV’s widow Elizabeth Woodville and Henry’s mother made a secret agreement that their children should marry. On Christmas Day in 1483, Henry pledged to marry King Edward IV’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York, who was also Edward IV’s heir since the presumed deaths of her brothers, King Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York. In 1485, having gained the support of the Woodvilles, the in-laws of the late King Edward IV, Henry Tudor sailed to Wales with a small French and Scottish force. On August 7, 1485, they landed in Mill Bay, Pembrokeshire, Wales, close to Henry’s birthplace. Henry Tudor then marched towards England accompanied by his paternal uncle Jasper Tudor and John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford.

On August 22, 1485, at the Battle of Bosworth Field, the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the last king of the House of York and the Plantagenet dynasty, 32-year-old King Richard III of England, lost his life and his crown. The battle was a decisive victory for the House of Lancaster, whose leader 28-year-old Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, became the first monarch of the House of Tudor. Henry Tudor’s first action was to declare himself king by right of conquest. This was because Henry’s claim to the throne through his mother’s descent was weak.

On October 28, 1485, King Henry VII processed to the Tower of London to spend the traditional night there. The next day, there was a grand procession to the Palace of Westminster with heralds, sergeants of arms, trumpeters, nobles, the Lord Mayor, and aldermen of London all preceding Henry VII. Henry rode on a horse under a silk canopy carried by four knights on foot. Behind Henry rode his paternal uncle Jasper Tudor, the newly created Duke of Bedford, who had helped to raise Henry after the death of his father. He was crowned in Westminster Abbey on October 30, 1485.

On January 18, 1486, Henry VII honored his pledge to marry Elizabeth of York, King Edward IV’s eldest child, thereby uniting the House of York and the House of Lancaster. Henry had Parliament repeal Titulus Regius, the act that declared King Edward IV’s marriage invalid and his children illegitimate, thereby legitimizing his wife.

********************

King Henry VIII of England

16th-century woodcut of the coronation of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon showing their heraldic badges, the Tudor Rose and the Pomegranate of Granada

- Child of King Henry VII of England and Elizabeth of York, daughter of King Edward IV

- Born: June 28, 1491

- House of Tudor

- Accession Date: April 21, 1509

- Coronation: June 24, 1509 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: William Warham Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: (1) Catherine of Aragon, Queen of England, crowned with her husband (2) Anne Boleyn, Queen of England, crowned June 1, 1533 at Westminster Abbey by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury (3) Jane Seymour, Queen of England, not crowned (4) Anne of Cleves, Queen of England, not crowned (5) Catherine Howard, Queen of England, not crowned (6) Catherine Parr, Queen of England, not crowned

- Death: January 28, 1547

- Unofficial Royalty: King Henry VIII of England

King Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon were married on June 11, 1509, and crowned together thirteen days later. Read more about their coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon.

********************

King Edward VI of England

King Henry VIII died on January 28, 1547, and his nine-year-old son succeeded him as King Edward VI. Henry VIII’s will named sixteen executors, who were to act as Edward’s Council until he reached the age of 18. However, a few days after Henry’s death, the executors decide to make King Edward VI’s maternal uncle Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, Lord Protector of the Realm, Governor of the King’s Person, and Duke of Somerset.

Edward’s coronation took place on February 20, 1547, at Westminster Abbey. The coronation was shortened because of the new king’s young age. King Edward VI traveled from Whitehall Palace to Westminster Abbey in a procession under a canopy carried by the barons of the Cinque Ports. The Coronation Chair had two cushions to help raise the nine-year-old king. King Edward VI’s coronation was the first Protestant coronation. Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury changed the coronation oath so that the “reformation of the Church could now be enabled by royal prerogative, the king as lawmaker”. The coronation was followed by a banquet in Westminster Hall.

********************

Lady Jane Grey, Queen of England

- Lady Jane Grey, Queen of England, disputed, reigned July 10, 1553 – July 19, 1553

- Parents: Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk and Lady Frances Brandon, daughter of King Henry VIII’s younger sister Mary Tudor and Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk

- Born: 1536 or 1537

- House of Grey

- No coronation

- Death: Executed February 12, 1554 for high treason

- Unofficial Royalty: Lady Jane Grey, Queen of England

As 15-year-old King Edward VI lay dying, probably of tuberculosis, in the late spring and early summer of 1553, many feared that the succession of his Catholic half-sister Mary would spell trouble for the English Reformation. John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland and Lord Protector of the Realm had arranged the marriage of his son Guildford Dudley and Lady Jane Grey, number four in the line of succession. Northumberland had King Edward VI compose a document “My devise for the succession” in which he passed over his half-sisters Mary and Elizabeth and the daughter of Mary Tudor, Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk. The crown was meant to go to the Duchess of Suffolk’s daughters and their male heirs. The unfortunate Lady Jane Grey was the eldest of the Duchess of Suffolk’s daughters.

On July 9, 1533 Lady Jane Grey was told that she was Queen, and reluctantly accepted the fact. However, the Privy Council switched their allegiance from Jane to Edward’s sister Mary and proclaimed her Queen on July 19, 1553. Mary arrived triumphantly in London on August 3, 1553, accompanied by her half-sister Elizabeth and a procession of over 800 nobles and gentlemen. Ultimately, Lady Jane, her husband Guildford Dudley, her father Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, and her father-in-law John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland would all lose their heads.

********************

Queen Mary I of England

The coronation of Queen Mary I was the first coronation of a queen regnant in England, a female ruler in her own right. Read about her coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of Mary I of England.

********************

Queen Elizabeth I of England

On November 17, 1558, Queen Elizabeth succeeded her elder half-sister Queen Mary I. on November 17, 1558. Upon hearing the news, Elizabeth reportedly said, “This is the Lord’s doing and it is marvelous in our eyes.” Elizabeth’s coronation took place on January 15, 1559, at Westminster Abbey in London, England. Read about her coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of Elizabeth I.

********************

King James I of England

- Child of Mary, Queen of Scots and her second husband and first cousin Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, both grandchildren of Margaret Tudor, daughter of King Henry VII of England and sister of King Henry VIII of England

- Born: June 19, 1566

- House of Stuart

- Accession Date: March 24, 1603

- Coronation: July 25, 1603 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Anne of Denmark, Queen of England, crowned with her husband

- Death: March 27, 1625

- Unofficial Royalty: King James I of England

Since none of the children of King Henry VIII had children, James VI, King of Scots was the senior heir of King Henry VII. James was the only child of Mary, Queen of Scots and her second husband (and first cousin) Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, both grandchildren of Margaret Tudor, daughter of King Henry VII of England and sister of King Henry VIII of England. On her deathbed, Queen Elizabeth I gave her assent that James should succeed her.

James was now James VI, King of Scots and King James I of England. The following Stuart monarchs of England were also Kings/Queens of Scots until 1707 when Scotland and England were united into a single kingdom called Great Britain: Charles I, Charles II, James II, Mary II, William III, and Anne.

The coronation of King James I of England was on July 25, 1603 at Westminster Abbey. His wife Anne of Denmark was crowned with him. Read about their coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of James I and Anne.

********************

King Charles I of England

- Child of King James I of England and Anne of Denmark

- Born: November 19, 1600

- House of Stuart

- Accession Date: March 27, 1625

- Coronation: February 2, 1626 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: Henrietta Maria of France, Queen of England, not crowned because she was Catholic and did not want to participate in a Church of England ceremony

- Death: The Civil War between the Royalists or Cavaliers (Charles’ supporters) and the Roundheads (Parliament’s supporters), which started in 1642, resulted in Charles being arrested, tried, and sentenced to death. He was beheaded on January 30, 1649.

- Unofficial Royalty: King Charles I of England

King Charles I was crowned in Westminster Abbey on February 2, 1626. This would be the last time that the original coronation regalia was used as the regalia was melted down or sold by Cromwell’s Parliamentarians after King Charles I was executed. The only piece of the old regalia that still exists is the Coronation Spoon, which had been sold off before it could be melted. In 1649, the spoon was sold for 16 shillings to Clement Kynnersley, Yeoman of the Removing Wardrobe, who returned it to King Charles II upon the restoration of the monarchy.

King Charles I lost his throne and his head during the English Civil War (1642 – 1651), fought between the Royalists (Cavaliers) and Parliamentarians (Roundheads). Oliver Cromwell was declared Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland. A Commonwealth and then a Protectorate remained the government until 1660 when Parliament formally invited the eldest son of the beheaded King Charles I to be the English monarch as King Charles II in what has become known as the Stuart Restoration.

********************

King Charles II of England

The coronation of King Charles II was delayed because of the extensive preparations necessary after more than ten years of the Commonwealth and because a new set of regalia had to be made as the previous regalia had been melted down during the Commonwealth period. This coronation was the last time the traditional procession from the Tower of London took place. It was the first time that tiered seating was constructed in the transepts so that the congregation could see the ceremony.

Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, was at the coronation and detailed the service in his diary. See this link: The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Tuesday 23 April 1661

********************

King James II of England

Coronation of King James II and Maria Beatrice of Modena

On April 23, 1685 at Westminster Abbey, King James II was crowned in a service that omitted Communion as James was Roman Catholic. The previous day, King James II and his wife had been privately crowned and anointed in a Catholic rite in their private chapel at the Palace of Whitehall. There seemed to be “bad omens” on the day of the coronation. The crown appeared to be about to fall off his head and at the moment of crowning the Royal Standard at the Tower of London was torn by the wind.

In 1688, King James II was effectively deposed during the Glorious Revolution. James II had converted to Catholicism and after his second wife gave birth to a Catholic son, there were fears that the throne would turn permanently into a Catholic throne. Willem III, Prince of Orange, the nephew and son-in-law of King James II, the husband of James II’s daughter Mary from his first marriage, vowed to safeguard the Protestant interest. James’s elder daughter Mary was declared Queen Mary II and she was to rule jointly with her husband and first cousin William (who was third in the line of succession after Mary’s sister Anne) who would be King William III.

After James II lost his throne, the Jacobite (from Jacobus, the Latin for James) movement formed. The goal of the Jacobites was to restore the Roman Catholic Stuart King James II of England/VII of Scotland and his Roman Catholic heirs to the thrones of England and Scotland. Since 1688, there have been Jacobite pretenders to the British throne.

********************

Queen Mary II of England

King William III of England

- Child of Willem II, Prince of Orange and Stadtholder of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, and Mary, Princess Royal, the eldest daughter of King Charles I of England. Through his mother, William was third in the line of succession after his wife Mary and her sister Anne.

- Born: November 14, 1650

- House of Stuart

- Accession Date: February 19, 1689

- Coronation: April 11, 1689 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Henry Compton, Bishop of London

- Spouse: Queen Mary II of England, crowned with her husband and co-ruler. Mary predeceased her husband William III who continued to reign until his death when he was succeeded by Mary’s younger sister and his first cousin Queen Anne.

- Death: March 8, 1702

- Unofficial Royalty: Unofficial Royalty: King William III of England, also Willem III, Prince of Orange

King William III and Queen Mary II were crowned as joint monarchs at Westminister Abbey on April 11, 1689. King William III was crowned in the Coronation Chair so a new chair was made for Queen Mary II’s use and is now in the Abbey collection. Henry Compton, Bishop of London officiated at William and Mary’s coronation because William Sancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury considered himself still bound by his oath of allegiance to King James II.

********************

Queen Anne of England, after 1707, Queen of Great Britain

Queen Anne suffered from gout and was carried to Westminster Abbey in an open sedan chair, with a low back to permit her train to flow out behind her. Once Queen Anne reached the door of Westminster Abbey, she got out of the sedan chair and walked down the aisle. Queen Anne wore crimson velvet over a golden robe embroidered with jewels, and a petticoat with bands of gold and silver lace between rows of diamonds.

********************

King George I of Great Britain

- Child of Ernst August, Elector of Hanover, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Sophia of the Palatinate (commonly referred to as Electress Sophia of Hanover), Sophia’s mother was Elizabeth Stuart, the second child and eldest daughter of King James I of England.

- Born: May 28, 1660 as Duke Georg Ludwig of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- House of Hanover

- Accession Date: August 1, 1714

- Coronation: October 20, 1714 at Westminster Abbey

- Crowned by: Thomas Tenison, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Spouse: his first cousin Sophia Dorothea of Celle, Electoral Princess of Hanover, divorced in 1694 before George I became king

- Death: June 11, 1727

- Unofficial Royalty: King George I of Great Britain

Queen Anne, the last of the Stuarts, had seventeen pregnancies which resulted in only three live births. In 1700, the last of those three children, Prince William, Duke of Gloucester, died six days after his eleventh birthday. Parliament was faced with a succession crisis as it did not want the throne to go to a Roman Catholic. The 1701 Act of Settlement was passed giving the throne to Sophia of the Palatinate, Electress of Hanover and her Protestant descendants. Sophia was a granddaughter of King James I and a first cousin of King Charles II and King James II.

Sophia died on June 8, 1714, at the age of 83. Her son Georg Ludwig of Brunswick-Lüneburg was now the heir to the British throne. Queen Anne died on August 1, 1714, only 54 days after Sophia died. The first Hanoverian, King George I, was only 56th in line to the throne according to primogeniture, but the nearest Protestant according to the 1701 Act of Settlement.

King George I did not speak much English and the Archbishop of Canterbury and the other clergy involved in the coronation spoke little German. Most of George I’s coronation was conducted in Latin, as both George I and the members of the clergy could understand it. While loyalists celebrated King George I’s coronation, there were riots in southern and western England in protest of the coronation of the first Hanoverian king.

********************

King George II of Great Britain

Queen Caroline’s dress was so encrusted with jewels that a pulley had to be devised to lift the skirt so she could kneel down at various points in the ceremony

The composer George Frederick Handel was commissioned to write four new anthems for the coronation, including the rousing Zadok the Priest which has been played at every British coronation ever since. It gives this writer, who has been fortunate to have sung it, goosebumps. See a performance at this link: YouTube: Zadok the Priest.

********************

King George III of Great Britain, after 1800 King of the United Kingdom

Exactly two weeks after their wedding, King George III and Queen Charlotte were crowned at Westminster Abbey. They were carried from St. James’s Palace to Westminster Hall in sedan chairs. At 11:00 AM, they walked the short distance from Westminster Hall to Westminster Abbey. The coronation ceremony was so long that they were not crowned until 3:30 PM. The traditional coronation banquet followed at Westminster Hall. Read about their coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of George III and Charlotte.

********************

King George IV of the United Kingdom

George IV and his wife Caroline both found each other equally unattractive and never lived together nor appeared in public together. Caroline was increasingly unhappy with her situation and treatment and negotiated a deal with the Foreign Secretary to allow her to leave the country in exchange for a very generous annual allowance. When King George III died in January of 1820, Caroline was determined to return to England and assert her rights as queen. On her way back to England, she received a proposal from her husband offering her an even more generous annual allowance if she would continue to live outside of England. Caroline rejected the proposal and received a royal salute of 21 guns from Dover Castle when she set foot again in England.

George IV was determined to be rid of Caroline and his government introduced a bill in Parliament, the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820, to strip Caroline of the title of queen consort and dissolve her marriage. The reading of the bill in Parliament was effectively a trial of Caroline. On November 10, 1820, a final reading of the bill took place, and the bill passed by 108–99. Prime Minister Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool then declared that since the vote was so close, and public tensions so high, the government was withdrawing the bill.

Coronation of King George IV

King George IV’s coronation was set for July 19, 1821, but no plans had been made for Caroline to participate. On the day of the coronation, Caroline went to Westminster Abbey, was barred at every entrance, and finally left. Three weeks later on August 7, 1821, Caroline died at the age of 53, most likely from a bowel obstruction or cancer.

George IV’s coronation was an extravagant affair that cost a staggering £230,000, equivalent in purchasing power today to about £32,306,101. A new crown was made containing over 12,000 diamonds. The 59-year-old obese king sweltered in his suit, thick velvet coronation robes, long curled wig, and plumed hat, and used nineteen handkerchiefs to mop his heavily perspiring brow.

********************

King William IV of the United Kingdom

Because King George IV and his wife Caroline had only one child, Princess Charlotte of Wales, born nine months after her parents’ wedding, had died in childbirth along with her stillborn son, King George IV was succeeded by his brother King William IV. In contrast to his extravagant brother King George IV, King William IV was unassuming and discouraged pomp and ceremony. On the day of his coronation, the doors of Westminster Abbey opened at 4:00 AM. The coronation procession left St. James Palace at 10:15 AM with King William IV dressed in an admiral’s uniform and Queen Adelaide in a white and gold dress. They arrived at Westminster Abbey at 11:00 AM and the coronation ended at 3:00 PM. There was no usual coronation banquet because King William IV decided it was too expensive. Read about the coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of William IV and Adelaide.

********************

Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom

A child of King William IV and Queen Adelaide would have succeeded to the throne as William’s two elder brothers King George IV and Prince Frederick, Duke of York had no surviving children. Sadly, William IV and Adelaide had no surviving child of their own. Their first child was born prematurely on March 27, 1819, as a result of Adelaide being ill with pleurisy. The baby girl was christened Charlotte Augusta Louisa and died the same day. Adelaide suffered a miscarriage on September 5, 1819. On December 19, 1820, Adelaide gave birth to a girl, Elizabeth Georgiana Adelaide, six weeks prematurely. Princess Elizabeth, who had been healthy despite being premature, died 12 weeks later on March 4, 1821, of the then-inoperable condition of a strangulated hernia. Twin boys were stillborn on April 23, 1822.

And so, it was the only child of King William IV’s next brother, the deceased Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, who would succeed him. Adelaide wrote to her widowed sister-in-law the Duchess of Kent, “My children are dead, but your child lives, and she is mine too.” That child was the future Queen Victoria.

Coronation of Queen Victoria

Nineteen-year-old Queen Victoria was crowned on June 28, 1838. The ceremony took five hours and because there had been very little rehearsal, there were many mishaps. No one except Queen Victoria and The Reverend Lord John Thynne, Deputy Dean of Westminster knew what should be happening. The coronation ring was painfully forced onto Queen Victoria’s wrong finger and 88-year-old John Rolle, 1st Baron Rolle “rolled” down the steps while making his homage to the Queen. A confused bishop incorrectly told Queen Victoria that ceremony was over and she had to come back to her seat to finish the service. Read about the coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of Queen Victoria.

********************

King Edward VII of the United Kingdom

The coronation of King Edward VII

June 26, 1902 was the date set for the coronation of King Edward VII and his wife Queen Alexandra. However, Edward VII developed appendicitis several days before and then developed peritonitis. Unless he postponed the coronation and immediately had surgery, he would die. Edward VII finally agreed and a new coronation date was set, August 9, 1902. Read more at Unofficial Royalty: Guts and Glory: Edward VII’s Appendix and the Coronation that Never Was.

By August 9, 1902, King Edward VII had recovered and the coronation proceeded as planned. Because of the postponement, many foreign delegations had left London and did not return in August, leaving their countries to be represented by their ambassadors. The 81-year-old Frederick Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury, who died four months later, was almost blind and refused to delegate any part of his duties. He had the prayers printed in large letters on cards so he could see them. He still misread some of the prayers and at the moment of the crowning, after he appeared to almost drop the crown, he placed it on Edward VII’s head backward. Read more about the coronation at Wikipedia: Coronation of Edward VII and Alexandra.

********************

King George V of the United Kingdom

First photographs of a coronation ever taken by Sir John Benjamin Stone. King George V and Queen Mary are in their chairs of estate during that part of the coronation service which precedes the anointing. On the left, are the bearers of the four swords. On either side of the King and Queen, are the supporting bishops.

This was the first coronation where photography was permitted in Westminster Abbey. Sir John Benjamin Stone was the official photographer. King George V and Queen Mary presented new hangings for the High Altar at Westminster Abbey which are still in use. The hanging is made of cream-white damask silk with an embroidered Crucifixion scene in the center flanked by angels holding shields with the Royal arms and coat of arms of St Edward the Confessor. Read more at the links below.

********************

King Edward VIII of the United Kingdom, The Duke of Windsor

King Edward VIII with his mother Queen Mary, a month before his abdication

The coronation of King Edward VIII was scheduled to take place at Westminster Abbey on May 12, 1937. Preparations were already underway and souvenirs were on sale when Edward VIII abdicated on December 11, 1936. His brother and successor King George VI instead was crowned on May 12, 1937. Read more at Wikipedia: Abandoned Coronation of Edward VIII.

********************

King George VI of the United Kingdom

Coronation of King George VI

King George V and his wife Queen Elizabeth were crowned on May 12, 1937, the day George VI’s elder brother, the abdicated King Edward VIII, had been scheduled to be crowned. Guests for the coronation began arriving at 6:00 AM. Many peers carried sandwiches in their coronets.

On the right side, Princess Elizabeth can be seen standing next to her grandmother Queen Mary while Princess Margaret rests her head next to her aunt Mary, Princess Royal; Credit – Getty Images

George VI’s mother Queen Mary attended the coronation, the first British dowager queen to do attend a coronation. Also in attendance were the king’s daughters, 11-year-old Princesses Elizabeth and 7-year-old Princess Margaret, who watched the coronation from the Royal Gallery, between their grandmother Queen Mary and their paternal aunt Mary, Princess Royal, Countess of Harewood.

There were some mishaps did occur during the service. Cosmo Gordon Lang, Archbishop of Canterbury thought he had been handed St. Edward’s Crown backward, a bishop stepped on King George V’s train, and another bishop put his thumb over the words of the oath when the King was about to read it.

Read more at the links below.

********************

Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom

A rather bored-looking 4 1/2-year-old Prince Charles at the coronation with his grandmother The Queen Mother and his aunt Princess Margaret; Credit – www.abc.net.au

The doors to Westminster Abbey opened at 6:00 AM for reporters and cameramen to get positioned. By 7:00 AM, the guests began taking their seats. Queen Elizabeth II entered the nave of the Abbey at 11:20 AM while the choirs sang the anthem “I Was Glad”. At 12:34 PM, she was crowned in the Coronation Chair with St. Edward’s Crown. At 1:28 PM, Queen Elizabeth II entered St Edward’s Chapel to exchange St. Edward’s Crown with the lighter Imperial State Crown and to into the Robe of purple velvet for the final procession. A packed lunch of smoked salmon, foie gras, sausage rolls, cheese, and biscuits was provided for the Queen and her party in the retiring rooms of the Abbey. The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh left Westminster Abbey at 2:53 PM and rode in the State Coach through the streets of London before returning to Buckingham Palace at 4:30 PM.

There is much information in the links below:

********************

King Charles III of the United Kingdom

With the accession of King Charles III, British monarchs will be descended from two children of Queen Victoria. Charles III’s mother was the great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria’s successor King Edward VII, and his father Prince Philip, The Duke of Edinburgh was the great-grandson of Queen Victoria’s daughter Princess Alice, Grand Duchess of Hesse and by Rhine.

To prepare for the coronation, Westminster Abbey was closed to visitors and worshippers from April 25, 2023 and will re-open on Monday, May 8, 2023.

********************

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Note: Many biography articles at Unofficial Royalty and Wikipedia royal biography articles were used to research this article besides the works cited below.

Works Cited

- A Guide to Coronations (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/a-guide-to-coronations (Accessed: March 22, 2023).

- A History of Coronations (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/a-history-of-coronations (Accessed: March 22, 2023).

- Coronation Chair (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/spotlight-on-coronations/coronation-chair (Accessed: March 22, 2023).

- Coronation Theatre (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/spotlight-on-coronations/coronation-theatre (Accessed: March 22, 2023).

- England and Scotland Monarch Coronations and Other Related British Royal Information (2022) Coronation of British Kings & Queens. Available at: http://kingscoronation.com/ (Accessed: March 22, 2023).

- Flantzer, Susan. (2019) Coronations after the Norman Conquest (1066 – present), Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/coronations-after-the-norman-conquest-1066-present/ (Accessed: March 22, 2023).

- Flanzter, Susan. (2019) Coronations before the Norman conquest (871 – 1066), Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/coronations-before-the-norman-conquest-871-1066/ (Accessed: March 22, 2023).

- Keay, Anna. (2012) The Crown Jewels. London: Thames and Hudson, Historic Royal Palace.

- Order of Service (no date) Westminster Abbey. Available at: https://www.westminster-abbey.org/about-the-abbey/history/coronations-at-the-abbey/spotlight-on-coronations/order-of-service (Accessed: March 22, 2023).

- Strong, Roy. (2005, 2022) Coronation – A History of the British Monarchy. London: William Collins.

- Weir, Allison. (2011) The Wars of the Roses. New York: Ballantine Books Trade Paperbacks.