by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2015

King Richard III of England; Credit – Wikipedia

King Richard III of England was born at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire, England, on October 2, 1452. He was the twelfth of the thirteen children of Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York and Cecily Neville, both great-grandchildren of King Edward III of England. Richard’s birthplace, Fotheringhay Castle, was the last place Mary, Queen of Scots was imprisoned, and it was the site of her execution. The castle fell into disrepair and was demolished in 1635.

Richard’s father was the Yorkist leader during the Wars of the Roses until his death. In 1399, Henry of Bolingbroke, the eldest son of John of Gaunt who was the third surviving son of King Edward III, overthrew his cousin King Richard II and assumed the throne as King Henry IV. Henry IV’s reigning house was the House of Lancaster as his father was Duke of Lancaster and Henry assumed the title upon his father’s death. Henry IV’s eldest son King Henry V retained the throne, but he died when his only child King Henry VI was only nine months old. Henry VI’s right to the crown was challenged by Richard, 3rd Duke of York, who could claim descent from Edward III’s second and fourth surviving sons, Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence and Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York.

During the early reign of King Henry VI, Richard, 3rd Duke of York held several important offices and quarreled with the Lancastrians at court. In 1448, he assumed the surname Plantagenet and then assumed the leadership of the Yorkist faction in 1450. The first battle in the long dynastic struggle called the Wars of the Roses was the First Battle of St. Albans in 1455 when the future King Richard III was not yet three years old. Richard, 3rd Duke of York and his second surviving son Edmund, Earl of Rutland were killed on December 30, 1460, at the Battle of Wakefield. Within a few weeks of Richard of York’s death, his eldest surviving son became King Edward IV, establishing the House of York on the throne following a decisive victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton. Edward IV was overthrown by the Lancastrians in 1470, and Henry VI once again assumed the throne. His second reign was short, and in 1471, Edward IV was once again king.

This was the atmosphere in which the future King Richard III spent his childhood. At his birth in 1452, no one could have predicted that 31 years later, Richard would be King of England. Richard had twelve siblings, and a number of them did not survive childhood.

- Joan of York (born and died 1438) – died in infancy

- Anne of York (1439 – 1476), married (1) Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter, had issue; married (2) Sir Thomas St. Leger, had issue

- Henry of York (born and died 1441), died shortly after birth

- King Edward IV of England (1442 – 1483), married Elizabeth Woodville, had issue

- Edmund, Earl of Rutland (1443 – 1460), killed at the Battle of Wakefield

- Elizabeth of York (1444 – circa 1503), married John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, had issue

- Margaret of York (1446 – 1503), married Charles I (the Bold), Duke of Burgundy, no issue

- William of York (born and died 1447) – died in infancy

- John of York (born and died 1448) – died in infancy

- George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence (1449 – 1478), married Isabella Neville, had issue; executed for treason

- Thomas of York (1450 – 1451) – died in infancy

- Ursula of York (born and died 1455) – died in infancy

As was customary at the time, Richard was sent to a noble’s household, Middleham Castle in Yorkshire, the home of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, for his education and training as a knight. Neville, known as Warwick the Kingmaker during the Wars of the Roses, was Richard’s first cousin. At Middleham Castle, Richard became acquainted with the Earl of Warwick’s younger daughter Lady Anne Neville, who would become his wife.

On November 1, 1461, Richard was created Duke of Gloucester by his brother King Edward IV. Richard was a loyal and loving brother and fought bravely in the later battles of the Wars of the Roses in support of his brother. In 1470, when King Edward IV was overthrown and Henry VI once again assumed the throne, Edward and Richard fled to Burgundy, where they knew they would be welcomed by their sister Margaret, the wife of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. The Duke of Burgundy provided funds and troops to Edward to enable him to launch an invasion of England in 1471. Although only eighteen years old, Richard played crucial roles in the Battle of Barnet and the Battle of Tewkesbury, which resulted in Edward’s restoration to the throne in the spring of 1471.

On July 12, 1472, Richard married Anne Neville. Anne’s father, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, the Kingmaker, had switched his allegiance from the House of York to the House of Lancaster, and he had arranged for Anne to marry King Henry VI’s only child, Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales to seal his allegiance with the Lancasters. Edward died at the Battle of Tewkesbury on May 4, 1471, while Warwick died at the Battle of Barnet on April 14, 1471. Anne’s elder sister Isabella had married Richard’s brother George, Duke of Clarence, three years earlier. These marriages caused a rift between the two brothers because George wanted all of Warwick’s estate for himself. Richard and Anne had one child, Edward of Middleham, born about December 1473 at Middleham Castle. Edward was a sickly child and spent most of his time at Middleham Castle.

Stained glass window of Richard and Anne Neville in Cardiff Castle; Credit – Wikipedia

On April 9, 1483, King Edward IV died and his twelve-year-old son succeeded him as King Edward V. Richard was named Lord Protector of his young nephew and moved to keep the Woodvilles, the family of Edward IV’s widow Elizabeth Woodville, from exercising power. The Queen sought to gain political power for her family by appointing family members to key positions and rushing the coronation of her young son. The new king was accompanied to London by his maternal uncle Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers and his half-brother Sir Richard Grey. Rivers and Grey were accused of planning to assassinate Richard, arrested, and taken to Pontefract Castle, where they were later executed without trial. Richard then proceeded with the new king to London, where Edward V was presented to the Lord Mayor of London. For their safety, King Edward V and his nine-year-old brother Richard, Duke of York, were sent to the Tower of London.

William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings had been a key figure in checking the power plays of the Woodvilles. However, things changed dramatically on June 13, 1483, during a council meeting at the Tower of London. Richard, supported by Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, accused Hastings and other council members of having conspired with the Woodvilles to kill him. The other alleged conspirators were imprisoned, but Hastings was immediately beheaded in the courtyard.

On June 22, 1483, a sermon was preached at St. Paul’s Cross in London declaring Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville invalid and his children illegitimate. This information apparently came from Robert Stillington, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, who claimed a legal pre-contract of marriage to Eleanor Butler, invalidating the king’s later marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. The citizens of London presented Richard with a petition urging him to assume the throne, and he was proclaimed king on June 26, 1483. Richard and his wife Anne were crowned in Westminster Abbey on July 6, 1483, and their son was created Prince of Wales. In January 1484, Parliament issued the Titulus Regius, a statute proclaiming Richard the rightful king

Contemporary illumination of Richard III, his queen Anne Neville, and their son Edward the Prince of Wales; Credit – Wikipedia

After Richard III’s accession, his nephews Edward and Richard were gradually seen less and less within the Tower of London. By the end of the summer of 1483, they had disappeared from public view altogether. Their fate remains unknown, and various theories promote their uncle Richard III, Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, and King Henry VII as ordering their murders. Bones belonging to two children were discovered in 1674 by workmen rebuilding a stairway in the Tower of London. On the orders of King Charles II, these remains were placed in an urn in Westminster Abbey. The bones were re-examined in 1933, and by measuring certain bones and teeth, it was concluded that the bones belonged to two children around the correct ages for the princes, but no positive identification was made. No further scientific examination has been conducted on the bones, which remain in Westminster Abbey, and DNA analysis has not been attempted.

On April 9, 1484, Richard’s son Edward of Middleham died at the age of 10. His burial site is unknown. Richard’s wife Anne Neville died on March 16, 1485, probably from tuberculosis. She was buried in Westminster Abbey, in an unmarked grave to the right of the High Altar, next to the door to Edward the Confessor’s Chapel. Richard did not survive her long. He lost his life and his crown at the Battle of Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485. On that day, Henry Tudor, the Lancastrian leader, became the first monarch of the House of Tudor, King Henry VII. The first Parliament of King Henry VII’s reign repealed the Titulus Regius, the statute proclaiming Richard the rightful king. Henry VII ordered his subjects to destroy all copies of it and all related documents.

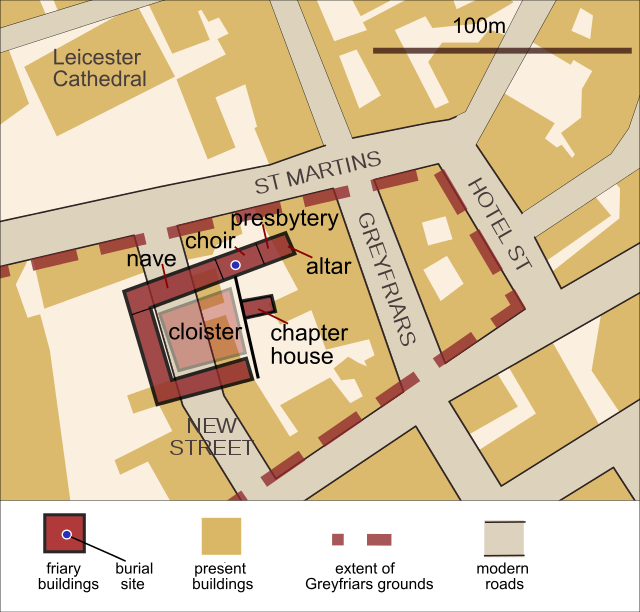

The site of Richard III’s remains remained a mystery for centuries. On September 12, 2012, an archaeological team announced that the human remains they found could be those of Richard III. DNA from Michael Ibsen, a direct descendant of Richard’s sister Anne of York, and an unnamed direct maternal line descendant matched the mitochondrial DNA extracted from the remains. On February 4, 2013, the University of Leicester confirmed that the remains were those of King Richard III. The remains of King Richard III were reburied at Leicester Cathedral on March 26, 2015.

For more information on Richard III’s death, the discovery of his remains, and his reburial at Leicester Cathedral, see Unofficial Royalty: Richard III – Lost and Found.

Tomb of King Richard III at Leicester Cathedral; By User:Isananni, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42870716

England: House of York Resources at Unofficial Royalty

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.