by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

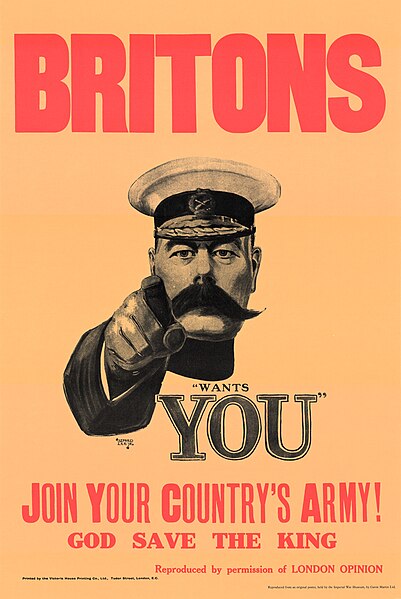

Catherine Parr, Queen of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Catherine Parr was the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII of England. She is the “survived” in the saying about Henry’s wives, “Divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived,” although she survived for only a year, and Anne of Cleves, Henry’s fourth wife, was the last of his wives to die (in 1557). Catherine was probably born in 1512 at her family’s townhouse in Blackfriars, London, England. She was the eldest child of Sir Thomas Parr and Maud Green. Sir Thomas was a descendant of King Edward III of England through Edward’s son John of Gaunt.

Catherine had two surviving siblings:

- William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton (circa 1513 – 1571), married (1) Anne Bourchier, 7th Baroness Bourchier, no issue; (2) Elizabeth Brooke, no issue; (3) Helena Snakenborg, no issue

- Anne Parr, Countess of Pembroke (circa 1515 – 1552), married William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke, had issue

William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton; Credit – Wikipedia

Thought to be Anne Parr; Credit – Wikipedia

Catherine’s father, Sir Thomas Parr was a courtier and served as Master of the Wards, Master of the Guards, and Comptroller of the Household of King Henry VIII. He also was High Sheriff of Northamptonshire and then High Sheriff of Lincolnshire. Catherine’s mother was a lady-in-waiting to Henry VIII’s first wife Catherine of Aragon, and it is thought that she named her daughter after the queen. Catherine’s father died in 1517 of sweating sickness, leaving a 25-year-old widow with three children under the age of five. Maud Parr did not marry again, fearing that the large inheritance from her deceased first husband would go to a second husband instead of her children. She carefully supervised her children’s education and just as carefully arranged their marriages.

At the age of 17, Catherine married Sir Edward Burgh, who was about four years older than his bride. Edward was the eldest son of Thomas Burgh, 1st Baron Burgh, but he was in poor health and predeceased his father, dying just four years after a childless marriage to Catherine.

In 1534, Catherine became the third wife to 41-year-old John Neville, 3rd Baron Latimer, her father’s second cousin and a first cousin of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, the Kingmaker, an important player during the Wars of the Roses. 22-year-old Catherine became stepmother to his two children from his first marriage, 14-year-old John Neville, the future 4th Baron Latimer, and 9-year-old Margaret Neville. Lord Latimer was a supporter of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1536 he was implicated in the Pilgrimage of Grace, an uprising in Yorkshire, England in 1536 against King Henry VIII’s break with the Roman Catholic Church, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and the policies of Henry’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell. Although no charges were brought against him, Lord Latimer’s reputation was tarnished. Catherine’s strong reaction against the uprising strengthened her belief in the reformed Church of England. Lord Latimer’s health began to go quickly downhill in 1542 and Catherine served as a good nurse to her ailing husband. He died in 1543 after a nine-year childless marriage to Catherine.

Catherine used her friendship with the late Catherine of Aragon to renew her friendship with Catherine’s daughter Mary (later Queen Mary I) to obtain a place in Mary’s household. A widow for the second time, 31-year-old Catherine fell in love with Thomas Seymour, brother of Henry VIII’s late third wife Jane Seymour, and the two hoped to marry. However, Henry VIII began to show an interest in Catherine and she felt it was her duty to choose Henry’s proposal of marriage over Thomas Seymour’s. Seymour was appointed an ambassador to the Netherlands to get him out of England.

King Henry VIII in 1542; Credit – Wikipedia

Catherine and King Henry VIII were married on July 12, 1543, at Hampton Court Palace. King Henry VIII now required a nurse rather than a wife. He had become obese and needed to be moved around with the help of mechanical devices. He was covered with painful, pus-filled boils and probably suffered from gout. His obesity and other medical problems can be traced from the jousting accident in 1536, in which he suffered a leg wound that never healed. The jousting accident is believed to have caused Henry’s mood swings, which may have had a dramatic effect on his personality and temperament. Catherine proved to be a good nurse to Henry and a kind stepmother to his three children. She was influential in Henry’s passing of the Third Succession Act in 1543 which restored both his daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, to the line of succession to the throne.

Catherine’s religious views were reform Protestant, in the sense of the definition of the word Protestant today. Her religious views incited a pro-Catholic/anti-Reform Protestant faction led by Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and Thomas Wriothesley, Lord Chancellor, to bring a charge of heresy against her in 1546. Catherine found out about this and eloquently pleaded her case successfully to Henry.

After Henry died in 1547, Catherine finally married Thomas Seymour, the uncle of King Edward VI. Catherine invited Elizabeth, King Henry VIII’s younger daughter, and her cousin Lady Jane Grey, to stay in the couple’s household at Sudeley Castle, located in the Cotswolds near Winchcombe, Gloucestershire, England. In early 1548, Catherine became pregnant, which was quite a surprise because she had failed to become pregnant during her first two marriages. During this time, Seymour began to take an interest in Elizabeth. Seymour had reportedly plotted to marry Elizabeth before marrying Catherine, and it was reported later that Catherine discovered the two in an embrace. Kat Ashley, Elizabeth’s governess later testified that not only did Catherine not mind the episodes of horseplay but that she actually assisted her husband. Whatever actually happened, Elizabeth was sent away from Sudeley Castle in May 1548 and never saw her beloved stepmother again.

Thomas Seymour; Credit – Wikipedia

In August 1548, Catherine and Seymour had a daughter, but tragically Catherine died on September 5, 1548, of puerperal fever (childbed fever). Her daughter Mary Seymour appears to have died young. Six months after Catherine’s death, Thomas Seymour was beheaded for treason. Catherine was buried in the chapel at Sudeley Castle. Lady Jane Grey, who lived with Catherine until her death, was the chief mourner at her funeral. Catherine’s grave was discovered in 1728 after the castle and the chapel had been left in ruins by the English Civil War. She was later re-interred by the Rector of Sudeley in 1817 and an elaborate tomb was built in her honor.

Tomb of Catherine Parr; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

England: House of Tudor Resources at Unofficial Royalty