by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

Isabella of France, Queen of England; Credit – Wikipedia

The wife of King Edward II of England, whom she later helped depose and then probably had murdered, Isabella of France was probably born in Paris in 1295. She was the sixth child of the seven children of King Philippe IV of France and Joan I, Queen of Navarre in her own right. Isabella had six siblings:

- Margaret (circa 1288 – 1294)

- King Louis X of France (1289 – 1316), married (1) Margaret of Burgundy, had one child Joan II, Queen of Navarre (2) Clementina of Hungary, no surviving issue

- Blanche (1290 – 1294), died young

- King Philippe V of France (1292/93 – 1322), married Joan II, Countess of Burgundy, had issue

- King Charles IV of France (1294 – 1328), married (1) Blanche of Burgundy, had issue; (2) Marie of Luxembourg, no surviving issue; (3) Jeanne d’Évreux, had issue

- Robert (1297 – 1308), died young

Isabella’s family in 1315: (left to right) Isabella’s brothers Charles and Philip, Isabella, her father Philip IV, her brother Louis, and her uncle Charles of Valois; Credit – Wikipedia

Isabella was brought up in the royal palaces in Paris, France the medieval Château du Louvre and the Palais de la Cité, where she was brought up by her nurse Théophania de Saint-Pierre, and given a good education. Isabella also learned by observing her parents, both reigning monarchs. The French royal court was one of the wealthiest and most influential in Europe. Her father Philippe IV of France strengthened the French monarchy with clever financing and administrative reform. Her mother Joan I of Navarre successfully defended her kingdom twice against the territorial claims of other European princes and played an active diplomatic role in the marriages of her children.

As a young child, Isabella was betrothed to the son and heir of King Edward I of England, the future King Edward II, intending to resolve the conflicts between France and England over England’s possession of Gascony and claims to Anjou, Normandy, and Aquitaine. However, King Edward I attempted to break the engagementl several times and the marriage did not occur until after his death. Isabella and King Edward II were married on January 25, 1308, at Boulogne Cathedral in France. The couple’s coronation was held in Westminster Abbey on February 25, 1308.

Isabella and Edward had four children:

- King Edward III of England (1312 – 1377), married Philippa of Hainault, had issue

- John of Eltham, 1st Earl of Cornwall (1316 – 1336), unmarried

- Eleanor of Woodstock (1318 – 1355), married Reinoud II of Guelders, had issue

- Joan of The Tower (1321 – 1362), married King David II of Scotland, no issue

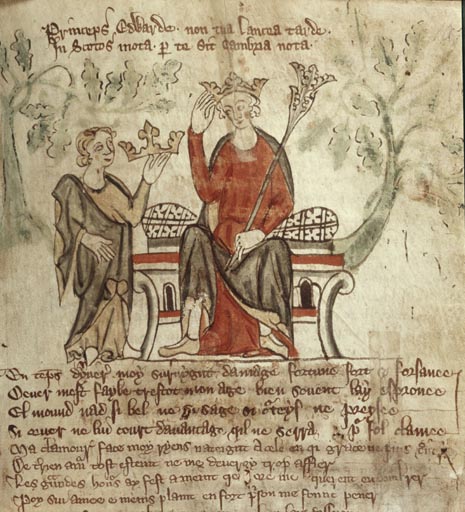

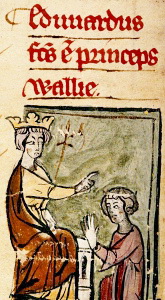

Edward II receiving the English crown in a contemporary illustration; Credit – Wikipedia

From the start of her marriage, Isabella was confronted with the close relationship between her husband and Piers Gaveston, described as “an arrogant, ostentatious soldier, with a reckless and headstrong personality.” The true nature of this relationship is not known and there is no complicit evidence that comments directly on Edward’s sexual orientation. Gaveston was part of the delegation that welcomed the young couple when they arrived in England after their marriage, and the greeting between Edward and Gaveston was unusually warm. Edward chose to sit with Gaveston at his wedding festivities rather than his bride and gave Gaveston part of the jewelry that belonged to Isabelle’s dowry. Eventually, with the influence of Isabella’s father, Dowager Queen Margaret, widow of King Edward III and Isabella’s aunt, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Edward agreed to exile Gaveston to Ireland. However, in a move that angered the barons, Edward made Gaveston Regent of Ireland. When Gaveston returned to England in 1312, he was hunted down and executed by a group of barons led by Edward’s uncle Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster and Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick.

From 1312 – 1321, there is no evidence that Edward and Isabella had a discordant marriage or that Isabella was not loyal to her husband. Isabella took a role in the reconciliation between Edward and the barons, who were responsible for the execution of Gaveston. However, during this time, Hugh Despenser the Elder became part of Edward’s inner circle, marking the beginning of the Despensers’ increased prominence at Edward’s court. His son, Hugh Despenser the Younger, became a favorite of Edward II. Edward was willing to let the Despensers do as they pleased, and they grew rich from their administration and corruption.

It is thought that Isabella first met and fell in love with Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March when he was a prisoner in the Tower of London, which was both a royal palace and a prison at that time. Isabella arranged for Mortimer’s death sentence to be commuted to life imprisonment. In 1323, Isabella helped arrange Mortimer’s escape from the Tower and his subsequent flight to France. During the next year, Isabella had enough of the Despensers and left Edward II, who made an unwise decision to send Isabella and their 12-year-old son Edward on a mission to France. Not surprisingly, Isabella met Mortimer in France where they planned to depose Edward II. Isabella gathered an army and set sail for England, landing at Harwich on September 25, 1326. With their mercenary army, Isabella and Mortimer quickly seized power. The Despensers were both executed and Edward II was forced to abdicate. Isabella’s son was crowned King Edward III, and Isabella and Mortimer served as regents for the teenage king.

Isabella landing in England with her son, the future Edward III in 1326; Credit – Wikipedia

King Edward II was imprisoned in Berkeley Castle and died there on September 21, 1327, probably murdered on the orders of Isabella and Mortimer. Relations between Mortimer and the young Edward III became more and more strained. In 1330, the 18-year-old King Edward III conducted a coup d’état at Nottingham Castle where Mortimer and Isabella were staying. Mortimer was arrested and then executed on fourteen charges of treason, including the murder of Edward II.

After the coup, Isabella was taken to Berkhamsted Castle and then held under house arrest at Windsor Castle until 1332, when she was moved to her own Castle Rising in Norfolk. Edward III granted his mother a yearly income of £3,000, which by 1337 had increased to £4,000. She enjoyed a regal lifestyle, maintaining minstrels, huntsmen, and grooms and being visited by family and friends. On August 22, 1358, Isabella died at the age of 63. She was buried at the now-destroyed Franciscan Church at Newgate, London. Her tomb did not survive the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of King Henry VIII.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

England: House of Plantagenet Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Index

- House of Plantagenet Index (1216 – 1399)

- British Royal Births, Marriages, Deaths, and Other Important Events

- Coronations after the Norman Conquest (1066 – present)

- History and Traditions: Norman and Plantagenet Weddings

- House of Plantagenet Burial Sites