by Scott Mehl © Unofficial Royalty 2016

Joséphine de Beauharnais, Empress of the French; Credit – Wikipedia

Joséphine de Beauharnais was the first wife of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French. She was born Marie-Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie (known as Rose), on June 23, 1763, in Les Trois-Îlets, Martinique, the eldest daughter of Joseph-Gaspard Tascher, Seigneur de la Pagerie, and Rose Claire des Vergers de Sannois.

Joséphine had two younger sisters:

- Catherine-Désirée Tascher de La Pagerie (1764 – 1777)

- Marie-Françoise Tascher de La Pagerie (1766 – 1791)

Joséphine’s childhood was spent on the Caribbean island of Martinique, a French possession, where her father owned a large plantation. However, after their home was destroyed by a hurricane in 1766, and combined with her father’s mismanagement of the land, the family lost much of their fortune. Young Rose did not attend school until she was ten years-old, when she was finally sent to a religious boarding school in the nearby town of Fort Royal, now Fort-de-France.

Joséphine’s aunt was the mistress of François V de Beauharnais, Viscount de Beauharnais, and had arranged a marriage between the Viscount’s son, Alexandre and Rose’s younger sister Catherine-Désirée in 1777. However, after Catherine-Désirée died in 1777, it was decided that Rose would become his bride. On December 13, 1779, she married Alexandre de Beauharnais in Noisy-le-Grand, France. Rose and Alexandre’s descendants sit on the thrones of Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, and Sweden.

Rose and Alexandre’s children:

- Eugène de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg (1781 – 1824), married Princess Augusta of Bavaria, had seven children including Joséphine of Leuchtenberg who married King Oscar I of Sweden, Auguste, Duke of Leuchtenberg who married Queen Maria II of Portugal, and Amélie of Leuchtenberg who married Pedro I, Emperor of Brazil

- Hortense de Beauharnais (1783 – 1837), married Louis Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, had three sons including Napoleon III, Emperor of the French

The marriage was unhappy, and Alexandre wasted most of his fortune. In December 1785, the couple separated. Rose and her children took up residence at the Pentemont Abbey in Paris. In March 1794, her estranged husband was arrested during the Reign of Terror. Despite their separation, Rose was also arrested in April 1794 and held in the Carmes prison. Alexandre was sentenced to death and executed by guillotine on July 23, 1794. Rose was released five days later, and the following year was able to reclaim her late husband’s possessions.

“The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries” painted by Jacques-Louis David, 1812. source: Wikipedia

Through those years of separation, Rose had several affairs and had become prominent in Parisian society. In 1795, she met her future husband Napoleon Bonaparte, and quickly became his mistress. They became engaged in January 1796 and married on March 9, 1796 in Paris. It was Napoleon who began calling her Joséphine, the name with which history has remembered her. Two days after the wedding, Napoleon left to fight in Italy, leaving his new wife alone. She soon began an affair with Hippolyte Charles, a lieutenant in the French forces. The affair lasted for several years until Napoleon threatened to divorce her, and she ended her relationship with Charles.

In April 1799, while her husband was away, fighting in the Egyptian Campaign, Joséphine purchased the Château de Malmaison, a few miles outside Paris. A large manor house set on nearly 150 acres, Malmaison was run down and needed significant restoration. Joséphine spent large amounts of money to create a home fit for an Emperor and Empress and devoted much of her time to developing the gardens and grounds. She had an orangery built to grow pineapple plants and a greenhouse where she grew several hundred plants that had not been grown in France before. She also developed a magnificent rose garden with over 250 different varieties of roses from around the world. In addition, she gathered a menagerie of animals that roamed in the gardens, many brought from Australia after the Baudin expedition of 1800-1803.

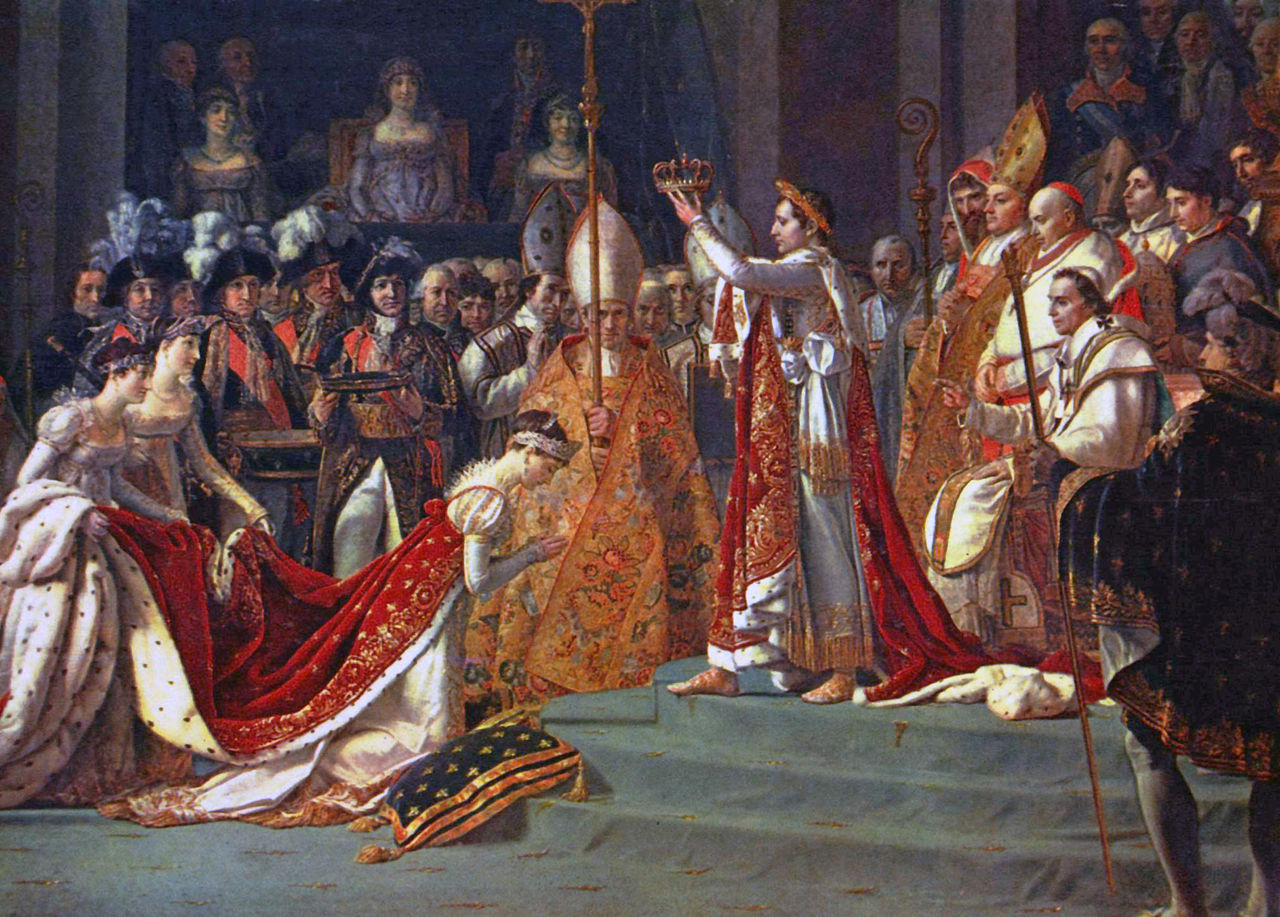

Crowning of Empress Joséphine, from “The Consecration of Emperor Napoleon I and Coronation of Empress Joséphine in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris on 2 December 1804” painted by Jacques-Louis David. source: Wikipedia

In November 1799, Napoleon was named First Consul of the French Republic, and the couple took up residence at the Tuileries Palace. Five years later, on May 18, 1804, Joséphine became Empress of the French when her husband was elected Emperor. They were crowned in a lavish coronation ceremony held at the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris, on December 2, 1804.

While Joséphine was able to provide a lovely home for her husband, the one thing she was unable to give him was an heir. Without a son, Napoleon had named Joséphine’s grandson (and his nephew), Napoleon Charles Bonaparte, as his heir. After the young Napoleon died in 1807, the Emperor considered finding another wife who could provide him with a son. In November 1809, he told Joséphine that he planned to divorce her and find a new wife.

Joséphine, painting by Andrea Appiani. c1808. source: Wikipedia

Joséphine agreed to a divorce, and an elaborate divorce ceremony was held on January 10, 1810. Joséphine retained her title as Empress and her rank at court and received an annual pension of 5 million francs. She received several residences, including the Château de Navarre in Normandy and the Élysée Palace in Paris. Napoleon would later ask her to return the Élysée Palace for his use and offered her the Château de Laeken in present-day Belgium instead. Napoleon had created Joséphine Duchess of Navarre at the time of their divorce. After living at the Château de Navarre for two years, Joséphine returned to the Château de Malmaison, where would live for the rest of her life.

On May 29, 1814, Joséphine died at the age of 50 from pneumonia. She was buried in the nearby church of Saint-Pierre-Saint Paul in Rueil-Malmaison, France, in a temporary vault. In 1825, Joséphine’s remains were transferred to the tomb ordered by her two children Eugene and Hortense. Napoleon’s true love had been his first wife and his last words were, “France, army, head of the army, Joséphine.”

Tomb of Empress Joséphine at Saint-Pierre-Saint-Paul Church; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

France Resources at Unofficial Royalty