by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

James Francis Edward Stuart circa 1720; Credit – Wikipedia

On February 6, 1685, King Charles II of England died after converting to Roman Catholicism on his deathbed. Although he had at least fourteen illegitimate children, he had no legitimate children. The throne passed to his brother who reigned as King James II, who had converted to Roman Catholicism in the 1670s. Catholic King James II was tolerated because he had two surviving, married daughters via his first marriage with Lady Anne Hyde who had been raised in the Church of England, and no surviving children with his second Catholic wife Maria Beatrice of Modena. It was expected that his elder Protestant daughter Mary would succeed him.

However, King James II set upon a course of restoring Catholicism to England. He issued a Declaration of Indulgence removing restrictions imposed on those that did not conform to the Church of England. England might very well have continued tolerating King James II knowing that his heirs were the Protestant daughters of his first wife. However, on June 10, 1688, the childless Queen Maria Beatrice gave birth to a Roman Catholic son. Immediately, false rumors swirled that the infant had been smuggled into the queen’s chambers in a warming pan.

Thus, James Francis Edward Stuart, created Prince of Wales on July 4, 1688, came into the world at St. James Palace in London. The infant’s father, King James II of England, was the son of the beheaded King Charles I of England and the first cousin of King Louis XIV of France. King James II’s mother was Henrietta Maria of France, daughter of the assassinated King Henri IV of France.

James Francis Edward with his mother Maria Beatrice of Modena; Credit – Wikipedia

James Francis Edward had two surviving elder half-sisters from King James II’s first marriage to Lady Anne Hyde:

- Queen Mary II of England (1662 – 1694), married her paternal first cousin William III, Prince of Orange who jointly reigned with her as King William III of England, no issue

- Queen Anne of Great Britain (1665 – 1714), married Prince George of Denmark, had 17 pregnancies, five live births, only one survived early childhood, Prince William, Duke of Gloucester who died at age 11

Between 1674 and 1684, James II’s second wife Maria Beatrice had ten pregnancies and gave birth to five live children

-

- Unnamed child (March 1674), miscarriage

- Catherine Laura Stuart (born and died 1673), died of convulsions

- Unnamed child (October 1675), stillborn

- Isabel Stuart (1676 – 1681)

- Charles, Duke of Cambridge (born and died 1677), died of smallpox

- Elizabeth Stuart (born and died 1678) died immediately after birth

- Unnamed child (February 1681), stillborn

- Charlotte Maria Stuart (born and died 1682), died of convulsions

- Unnamed child (October 1683), stillborn

- Unnamed child (May 1684), miscarriage

- James Francis Edward Stuart (James III and VIII to the Jacobites) (1688 – 1766) married Maria Clementina Sobieska, had issue, including Charles Edward Stuart, the Young Pretender

- Louisa Maria Teresa Stuart (1692 – 1712), unmarried, died of smallpox

James Francis Edward and his sister Louisa Maria Teresa in 1695; Credit – Wikipedia

On November 5, 1688, William III, Prince of Orange, the nephew and son-in-law of King James II, landed in England vowing to safeguard the Protestant interest. He marched to London, gathering many supporters. James II panicked and sent his wife and infant son to France. He tried to flee to France about a month later but was captured. William III, Prince of Orange had no desire to make his uncle a martyr, so he allowed him to escape. James II was received in France by his first cousin King Louis XIV, who offered him a palace and a pension.

Back in England, Parliament refused to depose James II but declared that having fled to France, James II had effectively abdicated the throne and the throne had become vacant. James II’s elder daughter Mary was declared Queen Mary II and she was to rule jointly with her husband William, who would be King William III. At that time, William, the only child of King James II’s elder sister Mary, Princess Royal was third in the line of succession after his wife and first cousin Mary and her sister Anne. This overthrow of King James II is known as the Glorious Revolution.

Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

James II, his wife, and his son settled at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, provided by King Louis XIV of France, where a court in exile, composed mainly of Scots and English Catholics, was established. James II was determined to regain the throne and landed in Ireland with a French force in 1689. He was defeated by his nephew William at the Battle of the Boyne on July 1, 1690, and was forced to withdraw once again to France. James II spent the rest of his life in France, planning invasions that never happened. In 1692, Maria Beatrice gave birth to a daughter Louisa Maria Teresa. James II died from a stroke on September 16, 1701, at St. Germain.

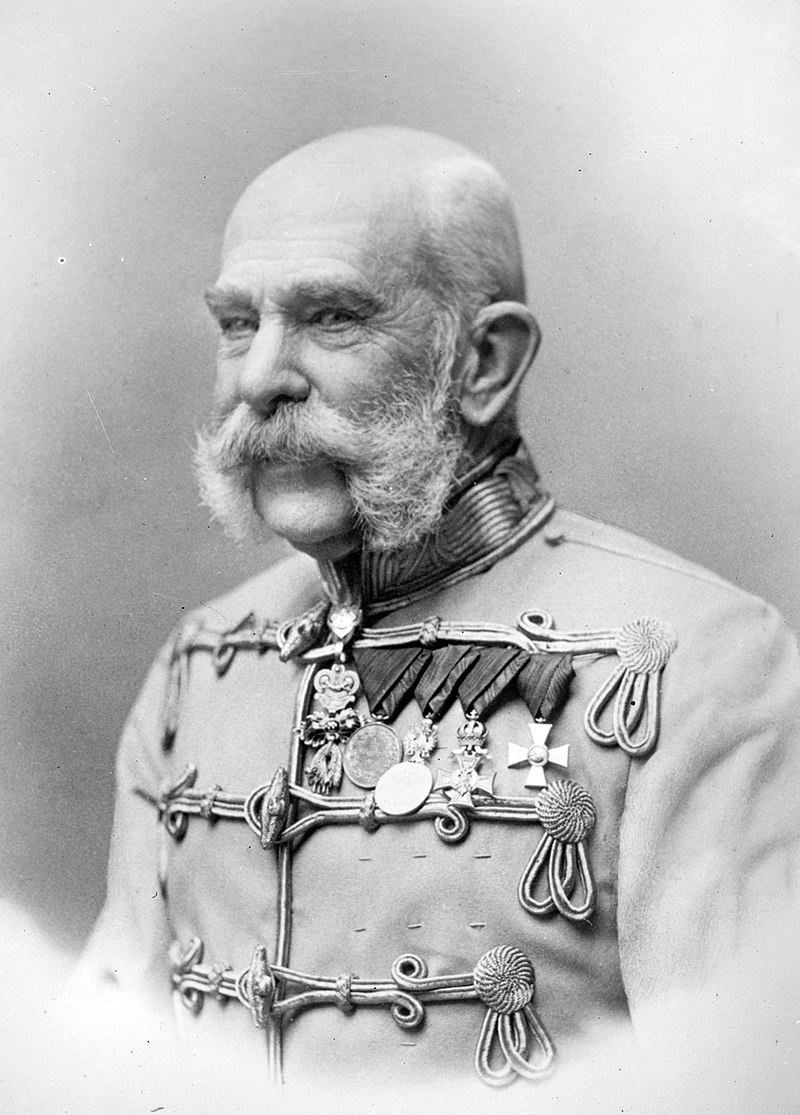

James Francis Edward Stuart; Credit – Wikipedia

Upon his father’s death, James Francis Edward (henceforth called James) was recognized by King Louis XIV of France as the rightful heir to the English and Scottish thrones. Spain, the Vatican, and Modena recognized him as King James III of England and VIII of Scotland and refused to recognize William III, Mary II, or Anne as legitimate sovereigns. As a result of James claiming his father’s lost thrones, he was attainted for treason in 1702 and his titles were forfeited under English law. After James II lost his throne, the Jacobite (from Jacobus, the Latin for James) movement formed. The goal of the Jacobites was to restore the Roman Catholic Stuart King James II of England/VII of Scotland and his heirs to the thrones of England and Scotland.

In 1708, James, with the support of King Louis XIV, attempted to land in Scotland, but the British Royal Navy intercepted the ships and prevented the landing. In 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht forced King Louis XIV of France to recognize the British 1701 Act of Settlement settling the succession on the Electress Sophia of Hanover (a granddaughter of James VI of Scotland and I of England) and her non-Roman Catholic heirs. Upon the death of Queen Anne in August of 1714, George, Elector of Hanover (son of Electress Sophia of Hanover) ascended the British throne as King George I. With the death of King Louis XIV in 1715, the French government found James an embarrassment and he was no longer welcome in France. In 1715, Scottish Jacobites started “The ‘Fifteen” Jacobite Rising, an unsuccessful attempt aimed at putting “James III and VIII” on the throne.

After the failure of the 1715 Rising, James lived in Avignon, then a Papal territory, now in France. In 1717, Pope Clement XI offered James the Palazzo Muti in Rome as his residence. James then organized a Jacobite court in Rome. Further efforts to restore the Stuarts to the British throne in 1719 and 1722 were unsuccessful.

On September 3, 1719, James Francis Edward Stuart married Maria Clementina Sobieska, granddaughter of King Jan III Sobieski of Poland, in the chapel of the episcopal palace of Montefiascone, Italy, in the Cathedral of Santa Margherita.

Wedding of James Francis Edward Stuart and Maria Clementina Sobieska; Credit – Wikipedia

The couple had two sons:

- Charles Edward Stuart, The Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie (1720 – 1788), married Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, no issue

- Henry Benedict Stuart (1725 – 1807), Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, unmarried, no issue

Charles Edward Stuart in 1745; Credit – Wikipedia

Cardinal Henry Benedict Stuart circa 1750; Credit – Wikipedia

After James’ failures to regain the throne, attention fell upon his son Charles Edward, The Young Pretender, whose Jacobite Rising of 1745 culminated in the final devastating loss for the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden. James Francis Edward Stuart died at his home, the Palazzo Muti in Rome, on January 1, 1766, and was buried in the crypt of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican. Besides the tombs in the crypt, in the left aisle of St. Peter’s Basilica is a monument to the Royal Stuarts, commemorating the last three members of the Royal House of Stuart: James Francis Edward Stuart, his elder son Charles Edward Stuart, and his younger son, Henry Benedict Stuart. With their deaths, the male line of the British Royal House of Stuart became extinct.

Tomb of James Francis Stuart and his two sons; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Monument to the Royal Stuarts in St. Peter’s Basilica; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

Abrufstatistik. “James Francis Edward Stuart.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 1 Oct. 2016.

“James Francis Edward Stuart.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 27 Sept. 2016. Web. 1 Oct. 2016.

Susan. “King James II of England.” British Royals. Unofficial Royalty, 7 Mar. 2016. Web. 1 Oct. 2016.