by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2019

Emperor Naruhito of Japan; Credit – Wikipedia

On May 1, 2019, the day 59-year-old Emperor Naruhito of Japan succeeded to the Chrysanthemum Throne after the abdication of his 85-year-old father Emperor Akihito, there were three people in the line of succession: the new Emperor’s 53-year-old brother Crown Prince Akishino, his 12-year-old nephew Prince Hisahito, and his 83-year-old uncle Prince Hitachi. There is male-line, male-only succession in Japan and probably there will not be another person in the line of succession until Prince Hisahito, born in 2006, marries and has a son. This situation screams succession crisis.

*********************

Imperial Sons

The succession to the throne of Japan depends upon Prince Hisahito; Credit – Imperial Household Agency

Since 1901, there have been only 12 males born into the Imperial Family. Four of those males had no children and an additional three of them had no sons.

*********************

Imperial Daughters

If Japan allowed female succession, Princess Aiko, the only child of Emperor Naruhito could be the heir to the throne; Credit – Imperial Household Agency

On May 1, 2019, the day Emperor Naruhito succeeded to the throne, there were six living princesses and seven living former princesses who, upon their marriage, gave up their imperial title and left the Imperial Family as required by the 1947 Imperial House Law. Compare that to only three princes living on that same date: Crown Prince Akishino, Prince Hisahito, and Prince Hitachi.

Living Princesses of the Blood Imperial, all unmarried

- Princess Aiko, born 2001, the only child of Emperor Naruhito

- Princess Kako of Akishino, born 1994, daughter of Crown Prince Akishino

- Princess Akiko of Tomohito, born 1981, daughter of Prince Tomohito, granddaughter of Prince Mikasa

- Princess Yōko of Tomohito, born 1983, daughter of Prince Tomohito, granddaughter of Prince Mikasa

- Princess Tsuguko of Takamado, born 1986, daughter of Prince Takamado, granddaughter of Prince Mikasa

Living former Princesses of the Blood Imperial who lost their Imperial status and title upon marriage

- Sayako Kuroda, formerly Sayako, Princess Nori, born 1969, daughter of Emperor Akihito, no children

- Atsuko Ikeda, formerly Atsuko, Princess Yori, born 1931, daughter of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito), no children

- Takako Shimazu, formerly Takako, Princess Suga, born 1939, daughter of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito), had one son

- Yasuko Konoe, formerly Princess Yasuko of Mikasa born 1944, daughter of Prince Mikasa, had one son

- Masako Sen, formerly Princess Masako of Mikasa, born 1951, daughter of Prince Mikasa, had two sons and one daughter

- Noriko Senge, formerly Princess Noriko of Takamado, born 1988, daughter of Prince Takamado, granddaughter of Prince Mikasa, no children yet

- Ayako Moriya, formerly Princess Ayako of Takamado, born 1990, daughter of Prince Takamado, granddaughter of Prince Mikasa, has two sons

- Mako Kaouro, formerly Princess Mako of Akishino, born 1991, daughter of Crown Prince Akishino, no children yet

Deceased Princess of the Blood Imperial with descendants who lost her Imperial status and title upon marriage

- Shigeko Higashikuni, formerly Shigeko, Princess Teru (1925 – 1961), daughter of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito), had four sons and one daughter

*********************

Jimmu, the traditional 1st Emperor of Japan, reigned 660 BC – 585 BC; Credit – Wikipedia

How did the succession work in the past?

Before the modernization of Japan by the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the succession was more or less based upon agnatic seniority, which meant the order of succession to the throne preferred the monarch’s younger brother over the monarch’s own sons. In theory, any male or female in a male line from the early Japanese monarchs who descended in direct male line from the first emperor Jimmu could succeed to the throne. This resulted in brothers, sons, and other males of the immediate male-line family, other male-line relatives, and occasionally distant male cousins becoming Emperor. Adoption was possible and was often used to increase the number of heirs. However, the adopted child had to be a child of another member of the imperial house.

*********************

Empress Go-Sakuramachi, the last reigning Empress of Japan; Credit – Wikipedia

Were there Empresses who reigned in Japan?

Before the Meiji Restoration, eight women reigned as Empress of Japan. Two of those empresses, after abdicating, became Empress again reigning under different names. All the empresses were male-line imperial daughters or granddaughters. Usually, an Empress reigned if a suitable male was not available or some branches of the Imperial Family were in dispute and a compromise was needed.

- Nukatabe, Empress Suiko, reigned 593 until 628

- Takara, Empress Kōgyoku, reigned 642 – 645, abdicated, then reigned again as Empress Saimei from 655 – 661

- Unonosasara, Empress Jitō, reigned 686 – 697

- Ahe, Empress Genmei, reigned 707 – 715

- Hitaka, Empress Genshō, reigned 715 – 724

- Abe, Empress Kōken, reigned 749 – 758, abdicated, then reigned again as Empress Shōtoku from 764 – 770

- Okiko, Empress Meishō, reigned 1629 – 1643

- Toshiko, Empress Go-Sakuramachi, reigned 1762 – 1771

*********************

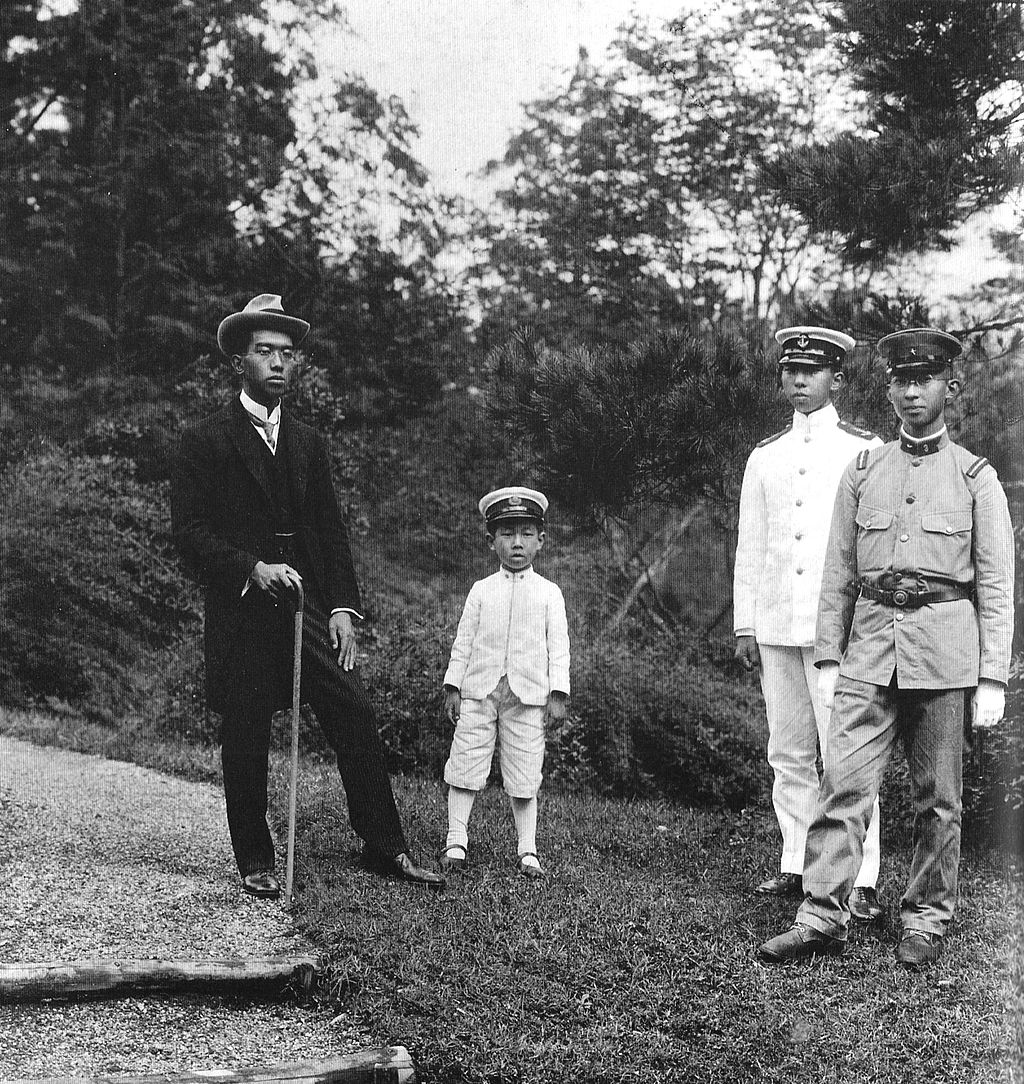

Emperor Meiji; Credit – Wikipedia

How did the succession change during the reign of Emperor Meiji (reigned 1867 – 1912)?

In the Constitution of the Empire of Japan enacted in 1890 during the reign of Emperor Meiji, Article 2 stated: “The Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by Imperial male descendants, according to the provisions of the Imperial House Law.” This meant there was no possibility of an Empress reigning.

Full Text of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan

Article 2 of the Constitution worked along with Chapter 1 of the 1889 Imperial Household Law (listed below) which stated succession was only by male descendants in the male line and that male descendants in the male line of the nearest collateral branch of the Imperial Family could succeed if the main-line had no males.

Chapter 1, Article IV below actually deals with sons of concubines of Emperors. If the Empress did not give birth to a son, the Emperor could take a concubine, and the son he had by that concubine would be recognized as heir to the throne. Both Emperor Meiji and Emperor Taishō were sons of concubines. Emperor Meiji was the last Emperor to take concubines.

In addition, the 1889 Imperial Household Law in Chapter VII Article XLII, The Imperial Family stated: “No member of the Imperial Family can adopt anyone as his son.” This ended a long-standing tradition.

Text of the 1889 Imperial Household Law Chapter I – Succession to the Imperial Throne

Full text of the 1889 Imperial Household Law

- Article I. The Imperial Throne of Japan shall be succeeded to by male descendants in the male line of Imperial Ancestors.

- Article II. The Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by the Imperial eldest son.

- Article III. When there is no Imperial eldest son, the Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by the Imperial eldest grandson. When there is neither Imperial eldest son nor any male descendant of his, it shall be succeeded to by the Imperial son next in age, and so on in every successive case.

- Article IV. For succession to the Imperial Throne by an Imperial descendant, the one of full blood shall have precedence over descendants of half-blood. The succession to the Imperial Throne by the latter shall be limited to those cases only in which there is no Imperial descendent of full blood.

- Article V. If there is no Imperial descendant, the Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by an Imperial brother and by his descendants.

- Article VI. If there is no such Imperial brother or descendant of his; the Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by an Imperial uncle and his descendants.

- Article VII. If there is neither such Imperial uncle nor descendant of his, the Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by the next nearest member among the rest of the Imperial Family.

- Article VIII. Among the Imperial brothers and the remote descendants, precedence shall be given, in the same degree, to the descendants of full blood, and to the elder over the younger.

- Article IX. If the Imperial heir is suffering from an incurable disease of mind or body, or when any weighty cause exists, the order of succession may be changed in accordance with foregoing provisions, with the advice of the Imperial Family Council with that of the Privy Council.

*********************

Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito), reigned 1926 – 1989; Credit – Wikipedia

How did the succession change after World War II?

The Constitution of Japan, written under the influence of the Allied Occupation of Japan led by American General Douglas MacArthur and enacted on May 3, 1947, was the new constitution for a post-war Japan. Article 2 of the new constitution stated: “The Imperial Throne shall be dynastic and succeeded to in accordance with the Imperial House Law passed by the Diet.” (The Diet is the legislature of Japan.)

Full text Constitution of Japan

The Imperial House Law of 1947 was passed by the Diet on January 16, 1947, and superseded the Imperial Household Law of 1889.

Full text Imperial House Law of 1947

The new Imperial House Law retained some laws from the 1889 Imperial Household Law: only males in the male line can succeed and members of the Imperial Family may not adopt children. There was a specific line of succession:

The Imperial Throne shall be passed to the members of the Imperial Family according to the following order:

- The eldest son of the Emperor

- The eldest son of the Emperor’s eldest son

- Other descendants of the eldest son of the Emperor

- The second son of the Emperor and his descendants

- Other descendants of the Emperor

- Brothers of the Emperor and their descendants

- Uncles of the Emperor and their descendants

In case there is no member of the Imperial Family listed above, the throne shall be passed to the member of the Imperial family next nearest in lineage. Precedence shall be given to the senior line and to the senior member.

A major change was caused by an effort to control the size of the Imperial Family. Members of collateral branches, other than the main branch descending from Emperor Taishō, would no longer have any titles or status. The males from the collateral branches could no longer succeed if the main line had no males. This measure caused eleven collateral branches of the Imperial Family to be eliminated and 51 people reduced to being commoners. In hindsight, perhaps this change went too far because it appears the Japanese Imperial Family is being gradually reduced to a nuclear family. In practicality, with the current succession laws, the Imperial Family now has only one person who can provide any heirs, a boy born in 2006 who will not marry for years.

*********************

Credit – https://www.amazonswatchmagazine.com

Besides being barred from the succession, what other issues affect Princesses of the Imperial Blood?

Under the 1889 Imperial Household Law, a female member of the Imperial Family, who married a commoner was excluded from membership in the Imperial Family. However, she could have been allowed, by special grace of the Emperor to retain her Imperial title.

Under the 1947 Imperial House Law, Imperial princesses similarly would lose their status as Imperial Family members and their Imperial title if they married outside the Imperial Family. However, there is no provision to retain the Imperial title with the Emperor’s permission as in the 1889 Imperial House Law. Losing imperial status, in particular, seems quite unfair. Before the 1947 Imperial House Law, princesses could marry princes from collateral branches and retain their position in the Imperial Family. With the elimination of collateral branches, princesses would have to marry their cousins to retain their status.

In addition, it seems ironic that a princess who cannot succeed to the throne, whose children will not be princes and princess, and whose children cannot succeed to the throne, loses her Imperial status if she marries a commoner when a prince who is in the line of succession, whose children will be princes and princesses and whose sons will be in the line of succession, can marry a commoner and retain his Imperial status.

*********************

Embed from Getty Images

Prince and Princess Akishino leave the hospital after the birth of Prince Hisahito

What has happened to relieve the succession crisis?

In reality, not much. On December 1, 2001, a daughter, Princess Aiko, was born to Crown Prince Naruhito and Crown Princess Masako (Emperor and Empress of Japan since May 1, 2019). There had not been a male born in the Imperial Family since the birth of Emperor Naruhito’s brother Crown Prince Akishino in 1965.

In 2002, shortly after the birth of Princess Aiko, 90-year-old Princess Takamatsu, the widow of Emperor Shōwa’s brother Prince Takamatsu, argued that Japan should change its male-only succession law. Writing in the monthly magazine Fujin-Koron, Princess Takamatsu said: “Like the Elizabethan and Victorian eras in Britain, there were many examples in foreign countries where a nation thrived under the rule of a queen.”

In 2004, then-Crown Prince Naruhito and Crown Prince Masako had been married for eleven years and still only had one child, a daughter. A ten-member advisory council was formed in late 2004 to advise the prime minister on revising the 1947 Imperial House Law dealing with the succession. On January 20, 2006, Prime Minister Junichirō Koizumi pledged to submit a bill to the Japanese Diet (legislature) allowing women to succeed to the throne so that the succession to the throne could be continued into the future in a stable manner. No timing or particular content of the bill was provided.

However, Prince Tomohito, the cousin of Emperor Akihito, had another view. Prince Tomohito suggested that to preserve male succession, distant cousins of the emperor should be brought back into the line of succession either by adoption or by the creation of new royal houses. More controversially, Prince Tomohito suggested that male members of the Imperial Family could once again take concubines to ensure a supply of sons.

On September 6, 2006, Prince and Princess Akishino, Emperor Akihito’s second son and his wife, had a son, Prince Hisahito. Princess Akishino was 40 years old at the time of Prince Hisahito’s birth and had two daughters, ages 15 and 12, so it would seem her childbearing days were over. Was the birth of Prince Hisahito merely a fortuitous occurrence or a very well-planned pregnancy with procedures done to ensure a male heir would be born? On January 3, 2007, Prime Minister Shinzō Abe announced that he would drop the proposal to allow women to succeed to the throne.

According to the article linked below from The Mainichi on April 25, 2019, “Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga said in an interview with the Mainichi Shimbun here on April 24 that the government will consider measures to secure the stability of Imperial succession after November, following a series of rituals related to the enthronement of the new emperor.” However, in November 2020, it was recommended that the discussion regarding the succession be shelved until Prince Hisahito becomes an adult and has children.

*********************

Embed from Getty Images

The Imperial Family of Japan at Emperor Akihito’s last New Year’s appearance on January 2, 2019

What could happen to relieve the succession crisis?

Japan has high levels of gender inequality. This is apparent in various aspects of social life from the family to employment to political representation. It is not surprising that gender inequality is also manifested in the Imperial Family. Japan, as a nation, has much work to do in the area of gender equality.

Japan is not the only monarchy with agnatic primogeniture, male-line, male-only succession. The Arab monarchies, which also have high levels of gender inequality, all follow some form of male-only succession. Liechtenstein also has male-line, male-only succession. A United Nations committee has questioned the compatibility of Liechtenstein’s succession law with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

All other European monarchies except for Monaco and Spain have absolute cognatic primogeniture in which the succession passes to the eldest child of the sovereign regardless of gender. (Note: In the United Kingdom, this applies only to those born after October 28, 2011. Those born before that date follow male-preference cognatic primogeniture.) Monaco and Spain have male-preference cognatic primogeniture in which a female can succeed if she has no living brothers and no deceased brothers who left surviving legitimate descendants.

At the very least, Japan could change its succession law to allow male-preference cognatic primogeniture. They could also do away with the law that stipulates Imperial princesses lose their status as Imperial Family members and their Imperial titles if they marry outside the Imperial Family. These measures would certainly relieve the succession crisis and bring Japan in line with the other highly developed monarchies.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Curtin, S. (2006). Japan’s Imperial Succession Debate and Women s Rights | The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. [online] Apjjf.org. Available at: https://apjjf.org/-J.-Sean-Curtin/1651/article.html [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Gender inequality in Japan. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_inequality_in_Japan [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Japanese absolute primogeniture debate. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_absolute_primogeniture_debate [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Line of succession to the Japanese throne. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Line_of_succession_to_the_Japanese_throne [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- En.wikisource.org. (2019). Constitution of Japan – Wikisource, the free online library. [online] Available at: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Constitution_of_Japan [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- En.wikisource.org. (2019). Imperial House Law – Wikisource, the free online library. [online] Available at: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Imperial_House_Law [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- En.wikisource.org. (2019). Imperial Household Law (1889) – Wikisource, the free online library. [online] Available at: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Imperial_Household_Law_(1889) [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- Joyce, C. (2005). Forget empress, let’s have concubines, says prince. [online] Telegraph.co.uk. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/japan/1502249/Forget-empress-lets-have-concubines-says-prince.html [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- Ndl.go.jp. The Constitution of the Empire of Japan | Birth of the Constitution of Japan. [online] Available at: http://www.ndl.go.jp/constitution/e/etc/c02.html [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- News.bbc.co.uk. (2002). BBC News | ASIA-PACIFIC | Princess backs Japan succession change. [online] Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/1746886.stm [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].