by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2017

Credit – Wikipedia

Matilda, the only daughter and the eldest of the two children of King Henry I of England and his first wife Matilda (born Edith) of Scotland, was born circa February 7, 1102, probably at the manor house at Sutton Courtenay in Oxfordshire, England. Matilda is sometimes known as Maud or Maude which are variants of Matilda. Matilda was the Latin or Norman form and Maud/Maude was the Saxon form.

- About.com: Matilda or Maud?

- Appellation Mountain: Name of the Day: Maud

- Behind the Name: Matilda

- Behind the Name: Maud

Matilda’s paternal grandparents were King William I of England (the Conqueror) and Matilda of Flanders. King Malcolm III of Scotland and Saint Margaret of Scotland were her maternal grandparents.

Matilda had one younger brother who was the heir to the throne:

- William Ætheling or (William Adelin) (1103 – 1120), married Matilda of Anjou, no issue

Matilda’s father King Henry I is the British monarch who had the most illegitimate children, at least 24. The most notable of the illegitimate children was the oldest, Robert Fitzroy, 1st Earl of Gloucester, who became Matilda’s chief military supporter during the civil war known as The Anarchy.

Nothing is known of Matilda’s early childhood. In 1108 or 1109, a marriage was contracted between Matilda and Heinrich V, Holy Roman Emperor who was about 16 years older than Matilda. In February 1110, Heinrich’s envoy Burchard, later Bishop of Cambrai, came to England to bring Matilda to Germany. Also accompanying Matilda were English clerics and Norman knights including her first cousin Henry of Blois, then an archdeacon, later Bishop of Winchester.

Matilda and Heinrich first met at Liège (now in Belgium). They then traveled to Utrecht (now in the Netherlands) where they were officially betrothed on April 10, 1110. On July 25, 1110, Matilda was crowned by Friedrich I, Archbishop of Cologne. Eight-year-old Matilda was then placed into the custody of Bruno, Archbishop of Trier, who educated her in the German language and culture and in the government of the Holy Roman Empire. On January 7, 1114, 12-year-old Matilda married 28-year-old Heinrich at Mainz Cathedral in Mainz, Archbishopric of Mainz, Holy Roman Empire, now in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Matilda, now with her own household, entered public life as the Holy Roman Empress. Matilda and Heinrich had no children.

Heinrich and Matilda; Credit – Wikipedia

On November 25, 1120, William Ætheling, King Henry I’s only legitimate son and Matilda’s brother, was returning to England from Normandy when his ship hit a submerged rock, capsized, and sank. William Ætheling and many others drowned. Although King Henry I had many illegitimate children, the tragedy of the White Ship left him with only one legitimate child, his daughter Matilda. Henry I’s nephews were his closest male heirs. Henry I’s first wife, Matilda of Scotland, had died in 1118. In 1121, 53-year-old Henry I, hoping for a male heir, married the 18-year-old Adeliza of Louvain.

The sinking of the White Ship; Credit – Wikipedia

Matilda’s husband Heinrich was suffering from cancer. He died on May 23, 1125, at the age of 44, leaving Matilda as a 23-year-old childless widow with the choice of becoming a nun or remarrying. Some offers of marriage started to arrive but she chose to return to Normandy in 1125 or 1126.

Henry I’s marriage to Adeliza of Louvain remained childless and the future of the Norman dynasty was at risk, so Henry looked to his nephews as possible heirs. His sister Adela had married Stephen II, Count of Blois and Henry considered two sons from this marriage: his nephews Stephen of Blois (the future King Stephen of England) and Theobold, Count of Blois and Count of Champagne. Somewhere around 1113 – 1115, Stephen first visited his uncle’s court in England. He soon became a favorite of his uncle who bestowed upon him lands won in battle, the County of Mortain (in France) and Alençon in southern Normandy. In 1125, King Henry I arranged for Stephen to marry Matilda of Boulogne, the only surviving child and heiress of Eustace III, Count of Boulogne.

Another option was William Clito, the only son of Henry I’s elder brother Robert Curthose, who was in open rebellion against his uncle for the Duchy of Normandy which Henry had taken from William Clito’s father. Upon Matilda’s return to her father’s court, Henry I’s preferred choice of a successor fell to his daughter and her successors. On Christmas Day 1126, King Henry I of England gathered his nobles at Westminster where they swore to recognize Matilda and any future legitimate heir she might have as his successors.

In 1126, King Henry I arranged for his daughter Matilda to marry Geoffrey of Anjou, eldest son of Fulk, Count of Anjou. Matilda was quite unhappy about the marriage. She was eleven years older than Geoffrey and marriage to a mere future Count would diminish her status as the widow of an Emperor. Nevertheless, the couple was married at the Cathedral of Saint Julian of Le Mans on June 17, 1128. Matilda and Geoffrey did not get along and their marriage was stormy with frequent, long separations. Matilda insisted on retaining her title of Empress for the rest of her life. In 1129, her husband became Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou when his father left for the Holy Land where he was to become King of Jerusalem.

Matilda and Geoffrey had three sons:

-

- King Henry II of England (1133–1189), married Eleanor of Aquitaine, had issue including King Richard II of England and King John of England

- Geoffrey, Count of Nantes (1134 – 1158), unmarried

- William, Viscount of Dieppe (1136 – 1164), unmarried

Geoffrey of Anjou; Credit – Wikipedia

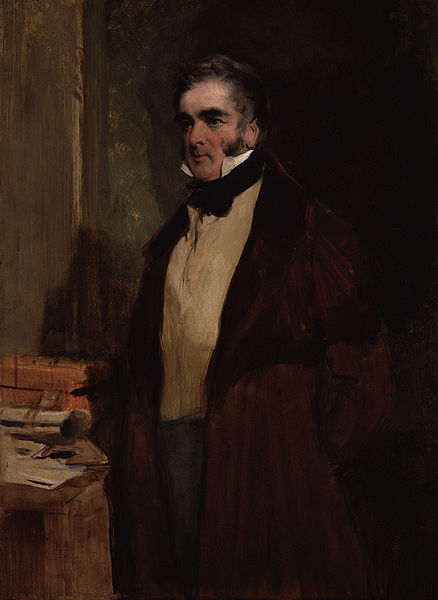

On December 1, 1135, King Henry I of England died. His nephew Stephen of Blois quickly crossed from Boulogne (France) to England, accompanied by his military household. With the help of his brother, Henry of Blois who was Bishop of Winchester, Stephen seized power in England and was crowned King Stephen of England on December 22, 1135. Empress Matilda did not give up her claim to England and Normandy, leading to the long civil war known as The Anarchy between 1135 and 1153.

King Stephen of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Matilda’s illegitimate half-brother Robert FitzRoy, 1st Earl of Gloucester rebelled against Stephen, starting the beginnings of civil war in England. Meanwhile, Matilda’s husband Geoffrey took advantage of the situation by invading Normandy. Matilda’s maternal uncle King David I of Scotland invaded the north of England and announced that he was supporting the claim of Matilda to the throne. Matilda gathered an invasion army and landed in England in September 1139 with the support of her half-brother Robert and several powerful barons.

In 1141, at the Battle of Lincoln, King Stephen was captured, imprisoned, and deposed while Matilda ruled for a short time. Stephen’s brother Henry, Bishop of Winchester turned against his brother and a church council at Winchester declared that Stephen was deposed and declared Empress Matilda “Lady of the English.” Stephen’s queen, Matilda of Boulogne, rallied Stephen’s supporters and raised an army with the help of William of Ypres, Stephen’s chief lieutenant. Matilda of Boulogne recaptured London for Stephen and forced Empress Matilda to withdraw from the siege of Winchester, leading to Stephen’s release in 1141 in exchange for the Empress’ illegitimate brother Robert of Gloucester who had also been captured.

Battle of Lincoln; Credit – Wikipedia

After the Battle of Lincoln, Empress Matilda established her base at Oxford Castle. In December 1141, Stephen unexpectedly marched upon Oxford. He attacked and seized the town and then besieged Matilda at Oxford Castle. Matilda responded by escaping from the castle. The popular version of the story has Matilda dressed in white as camouflage in the snow, being lowered down the wall with several knights, and escaping into the night. The chronicler William of Malmesbury, however, suggests Matilda was not lowered down the walls but instead sneaked out of one of the gates. Matilda safely reached Abingdon-on-Thames and Oxford Castle surrendered to Stephen the next day.

By the mid-1140s, the fighting had slowed down, there was a stalemate and the succession began to be the focus. Empress Matilda returned to Normandy in 1147. In the same year, Matilda’s husband and her eldest son Henry FitzEmpress, the future King Henry II, mounted a small, unsuccessful mercenary invasion of England. Matilda remained in Normandy where she focused on stabilizing the Duchy of Normandy and promoting her son’s rights to the English throne.

Stephen unsuccessfully attempted to have his son Eustace recognized by the Church as the next King of England. By the early 1150s, most of the barons and the Church wanted long-term peace. Ironically, Stephen’s son Eustace died on the same day that Henry FitzEmpress’ eldest son William was born. Although William died when he was three years old, the irony of the birth and the death on the same day must have been noticed at the time.

When Henry FitzEmpress re-invaded England in 1153, neither side’s forces were eager to fight. After limited campaigning and the siege of Wallingford, Stephen and Henry agreed upon a negotiated peace, the Treaty of Winchester, in which Stephen recognized Henry as his heir. Stephen died on October 25, 1154, and Henry ascended the throne as King Henry II, the first Angevin King of England.

Empress Matilda lived long enough to see her son Henry firmly established on the English throne. She spent the rest of her life in Normandy, often acting as Henry’s representative and presiding over the government of the Duchy of Normandy. Matilda helped Henry deal with several diplomatic issues and was involved in attempts to mediate between Henry and his Chancellor Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury in the 1160s. As she grew older, Matilda paid increasing attention to church affairs and her personal faith, although she continued to remain involved in governing Normandy.

Matilda, aged about 65, died on September 10, 1167, in Rouen, Duchy of Normandy, now in France. She was buried before the high altar of Bec Abbey in Bec-Hellouin, Duchy of Normandy, now in France. Her epitaph read: “Great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in her offspring: here lies Matilda, the daughter, wife, and mother of Henry”. Her tomb was damaged in a fire in 1263 and later restored in 1282, before being destroyed in 1421 by English mercenaries during the Hundred Years War between England and France. In 1684, some of her remains were found and reburied in a new coffin. Matilda’s remains were lost again after the destruction of the abbey church by Napoleon’s army but were found once more in 1846, and then reburied at Rouen Cathedral in Normandy, France.

Matilda is one of the main characters in Sharon Kay Penman‘s excellent historical fiction novel When Christ and His Saints Slept. The years of the civil war fought by Matilda and Stephen serve as a backdrop for Ellis Peters‘s historical detective series about Brother Cadfael, set between 1137 and 1145.

Rouen Cathedral; By Daniel Vorndran / DXR, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31189606

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

“Empress Matilda.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 9 Dec. 2016. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

“Mathilde l’Emperesse.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Jan. 1114. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

“Matilda (England).” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

Susan. “King Henry II of England.” British Royals. Unofficial Royalty, 7 Aug. 2016. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell, 1996. Print.