by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2017

Queen Victoria in her coronation robes by Sir George Hayter; Credit – Wikipedia

UPDATE: Since this article was published we have added a new area Queen Victoria’s Inner Circle. We have extended articles on some of those who served Queen Victoria and some of her relatives who lived during her reign (1837 – 1901). Many of the people listed were seen in the television series Victoria but their true life story may be very different than the story depicted in the series.

Victoria is a British television series created by Daisy Goodwin, a British television producer and novelist, and written by Goodwin and Guy Andrews. It was first shown in the United Kingdom on ITV from August – October 2016. In the United States, the series was shown on PBS as part of Masterpiece from January – March 2017. Series 1 has eight episodes. In the United States, episodes one and two were shown together on January 15, 2017.

Victoria can be classified as historical fiction in the performing arts, a historical period drama television series, and therefore, the creators had some poetic license to change the facts of the real world to make their story more interesting. Historical fiction can serve a useful purpose as it humanizes historical figures so we can better understand them. Whatever form historical fiction takes, its creators have to decide how far to take their poetic license. Certainly, we do not know exactly everything historical figures said, all their actions, all their thoughts, etc. The creators need to determine these things based on their knowledge and research of the historical person.

For instance, historical fiction in the performing arts may need to take poetic license in the settings. Anyone who has been to Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, and Westminster Abbey will know that scenes in Victoria that occur in those settings were not filmed at those settings, simply because filming there is basically impossible. But how much poetic license should historical fiction creators take with facts? Should they change the characteristics of a real person because it will make the plot more dramatic? Should they change the facts so much that a real person is misrepresented or even defamed? How much should real events change? What responsibility do the creators of historical fiction have to tell the truth that the historical facts reveal? Many historical fiction novelists feel the need to inform their readers when they take poetic license with facts by offering an explanation in an afterword.

Historical fiction, whatever its form, can introduce a person to a historical period, event or persons. It can cause the reader or viewer to further investigate the history and this is a very positive thing. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and actually nearly all of the real people in Victoria, have had biographies and other informational texts written about them. Queen Victoria’s diaries and correspondence with several of her children can be read. The information is readily available through libraries, bookstores (both online and brick-and-mortar), newspaper archives, and the Internet.

Below are inaccuracies (and some information on real people) from the first four episodes of the television series Victoria shown in the United States 1/15/17-2/5/17. We encourage our readers to learn more about Queen Victoria and her family. You can start right here at Unofficial Royalty. See the links below.

Inaccuracies in Victoria – Episodes 1 – 4 Shown in the USA 1/15/17 – 2/5/17

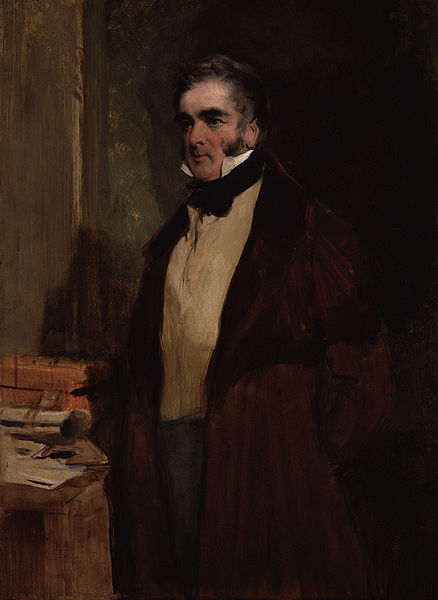

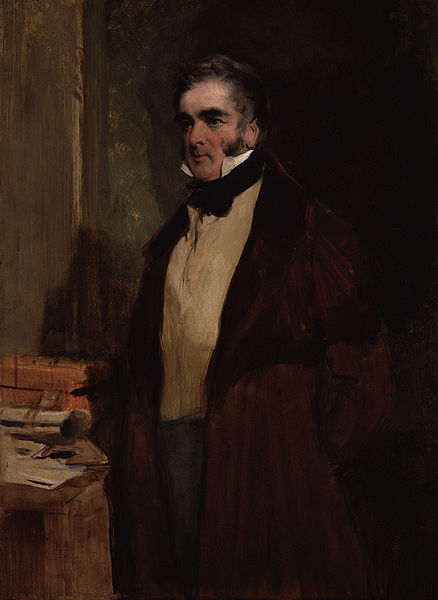

Lord Melbourne by Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, 1836; Credit – Wikipedia

Lord Melbourne – William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne (1779 – 1848): In the series, Queen Victoria and her Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, appear to have a relationship that borders on the romantic. The Lord Melbourne infatuation is nonsense. Victoria never knew her father as he died when she was eight months old. Melbourne was a father figure to Victoria and was 40 years older than her.

Unofficial Royalty: William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne

Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover, Duke of Cumberland by Edmund Koken, circa 1842; Credit – Wikipedia

Ernest, King of Hanover, Duke of Cumberland (1771 – 1851): Ernest was the fifth son and eighth child of the fifteen children of King George III of the United Kingdom who was also King of Hanover in Germany. At the time of Victoria’s accession to the throne, Ernest was the eldest surviving son of King George III and the first in the line of succession to the British throne until Victoria had children. The storyline with the Duchess of Kent, John Conroy, and Uncle Ernest (Duke of Cumberland and King of Hanover) trying to frame Victoria as insane never happened. Ernest arrived in Hanover (Germany) eight days after his brother King William IV died on June 20, 1837 to take up his duties as the new King of Hanover. Victoria could not succeed to the Hanover throne because it allowed for only male succession. Ernest was not in England and did not attend any balls or other events as shown in the series.

Unofficial Royalty: King Ernest Augustus I of Hanover, Duke of Cumberland

Sir John Conroy by Henry William Pickersgill, 1837; Credit – Wikipedia

Sir John Conroy, 1st Baronet (1786 – 1854) was the equerry of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, father of Queen Victoria. After Edward’s death, Conroy served as comptroller of the Duchess of Kent‘s household. The Duchess developed a very close relationship with Conroy, who wanted to use his position with the mother of the future queen to obtain power and influence. Conroy and the Duchess tried to control and influence Victoria with their Kensington System, a strict and elaborate set of rules. When Victoria became Queen, she immediately dismissed Conroy from her household, but she could not dismiss him from her mother’s household and she did, as shown in Victoria, send both her mother and Conroy off to a distant wing of the palace and cut off personal contact with them. Conroy was finally persuaded by the Duke of Wellington to leave the Duchess of Kent’s household in 1839.

Unofficial Royalty: Sir John Conroy, 1st Baronet

Marianne Skerrett attributed to Dr. Ernest Becker, circa 1859; Photo Credit – https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/2906440/miss-mariann

Marianne Skerrett (1793 – 1887) was the Head Dresser and Wardrobe-Woman to Queen Victoria from 1837 to 1862. Marianne was born in 1793, so she was 44 years old when Victoria became queen, not a young woman as in the series, but that is far from the only inaccuracy. Carolly Erickson has references to Marianne in her biography of Queen Victoria, Her Little Majesty. From Erickson’s book: Marianne Skerrett was “the head of Victoria’s wardrobe, overseeing all the practical work of ordering all her clothing, shoes, hats, gloves, and undergarments…She kept the wardrobe accounts, checking all the bills to make certain no one tried to cheat her mistress, and supervised the purveyors, hairdressers, dressmakers and pearl-sewers whose task it was to keep the royal wardrobe in good repair.” In addition, Marianne and Victoria had a lot in common. From Erickson’s book: “Both were intelligent, loved animals, spoke several languages…shared a great interest in paintings and painters. Marianne was well educated, with cultivated tastes, and in time to come Victoria would rely on her to help with the purchase of paintings and in corresponding with artists.” This is a far cry from the Marianne Skerrett in the series where she is depicted as having worked in a brothel, stealing lace from Victoria to give to her cousin to sell, and also stealing some jewels until her conscience then causes her to return the jewels.

Unofficial Royalty: Marianne Skerrett

Prince Albert by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1842; Credit – Wikipedia

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819 – 1861): Victoria fell in love with Albert at first sight. First cousins Victoria and Albert met for the first time in 1836 when Albert and his elder brother Ernst visited England. Seventeen-year-old Victoria seemed instantly infatuated with Albert. She wrote to her uncle Leopold, “How delighted I am with him, and how much I like him in every way. He possesses every quality that could be desired to make me perfectly happy.” On October 10, 1839, Albert and Ernst arrived in England again, staying at Windsor Castle with Victoria, who was now Queen. This is the meeting in the series and was not as antagonistic as shown in the series. That night, Victoria wrote in her journal, “It was with some emotion that I beheld Albert – who is beautiful.” On October 15, 1839, the 20-year-old monarch summoned her cousin Albert and proposed to him. Albert accepted, but wrote to his stepmother, “My future position will have its dark sides, and the sky will not always be blue and unclouded.”

Unofficial Royalty: Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, The Prince Consort

King Leopold I of Belgium by Franz Xaver Winterhalter; Credit – Wikipedia

King Leopold I of Belgium (1790 – 1865) was born Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, the youngest son of Franz Friedrich Anton, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. Among his siblings was the mother of Queen Victoria and the father of Prince Albert. In 1816, Leopold married Princess Charlotte of Wales, the only child of George, Prince of Wales who would succeed his father King George III as King George IV. Charlotte would have succeeded her father on the throne, but on November 6, 1817, a great tragedy struck the British Royal Family. After a labor of over 50 hours, Charlotte delivered a stillborn son. Several hours later, twenty-one-year-old Princess Charlotte, the only child of George, Prince of Wales, and King George III’s only legitimate grandchild died of postpartum hemorrhage.

Leopold had received an annuity from Parliament of £60,000 upon his marriage to Princess Charlotte. Charlotte was not Queen and did not have the funds her cousin Queen Victoria had, so perhaps it made sense that her husband would have a larger allowance than the husband of Queen Victoria. When Charlotte died, Leopold’s annuity was reduced to £50,000. He was allowed to continue living at Claremont House which Parliament had purchased as a wedding gift for Charlotte and Leopold. In 1818, during the flurry of marriages of the childless sons of King George III, made to produce an heir to the throne after Charlotte’s death, Leopold’s sister married Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, King George III’s fourth son. Their daughter, Alexandrina Victoria, was born on May 21, 1819, and eight months later the Duke of Kent died. After his death, his widow the Duchess of Kent (Leopold’s sister) and her daughter Alexandrina Victoria were given little financial support from Parliament. Leopold helped support them with funds from his annuity.

In August of 1830, the southern provinces (modern-day Belgium) of the Netherlands rebelled against Dutch rule. On April 22, 1831, Leopold was asked by the Belgian National Congress if he wanted to be King of the Belgians. Leopold swore allegiance to the new Belgian constitution on July 21, 1831, and became the first King of the Belgians.

In the series, it was stated that Leopold converted to Roman Catholicism and was, at that time, paying for the upkeep of his mistress, an actress, with his annuity. Both of these claims are false. Belgium is a mostly Catholic country and Leopold’s second marriage was to a Catholic, Princess Louise-Marie of Orléans, daughter of Louis-Philippe I, King of the French, and their children were raised as Catholics, but Leopold remained Lutheran for his entire life. Leopold did have an affair with an actress from 1828 – 1829, but this was when he was a widower living in England. Prince Leopold resigned his annuity in a letter dated July 15, 1831, to Prime Minister Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey prior to becoming King of Belgium on July 21, 1831, because he did not think it proper for a foreign monarch to be receiving funds from another country.

Unofficial Royalty: King Leopold I of Belgium

Christian Friedrich, Baron Stockmar by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1847; Credit – Wikipedia

Where is Baron Stockmar?

Christian Friedrich, Freiherr von Stockmar (Baron Stockmar) (1787 – 1863) was a physician and a statesman from Saxe-Coburg and Gotha who was sent to Victoria in 1837, the year of her accession, by her uncle King Leopold I of Belgium to advise her. Stockmar had accompanied Leopold to England when he married Princess Charlotte of Wales in 1816 and served as his personal physician, private secretary, comptroller of the household, and political advisor. When Albert and Ernst made a six-month tour of Italy in early 1839, Stockmar accompanied them. Baron Stockmar was Albert’s negotiator during the discussions regarding the marriage of Victoria and Albert and stayed in England after the marriage of Victoria and Albert, acting as their unofficial advisor. He was an important person to both Victoria and Albert and is missing from the series.

Unofficial Royalty: Christian Friedrich, Baron von Stockmar

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.