by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Prince Alexander Danilovich Menshikov; Credit – Wikipedia

Favorite: a person treated with special or undue favor by a king, queen, or another royal person

Patronymics

- In Russian, a patronymic is the second name derived from the father’s first name: the suffix -vich means “son of” and the suffixes -eva, -evna, -ova, and -ovna mean “daughter of”.

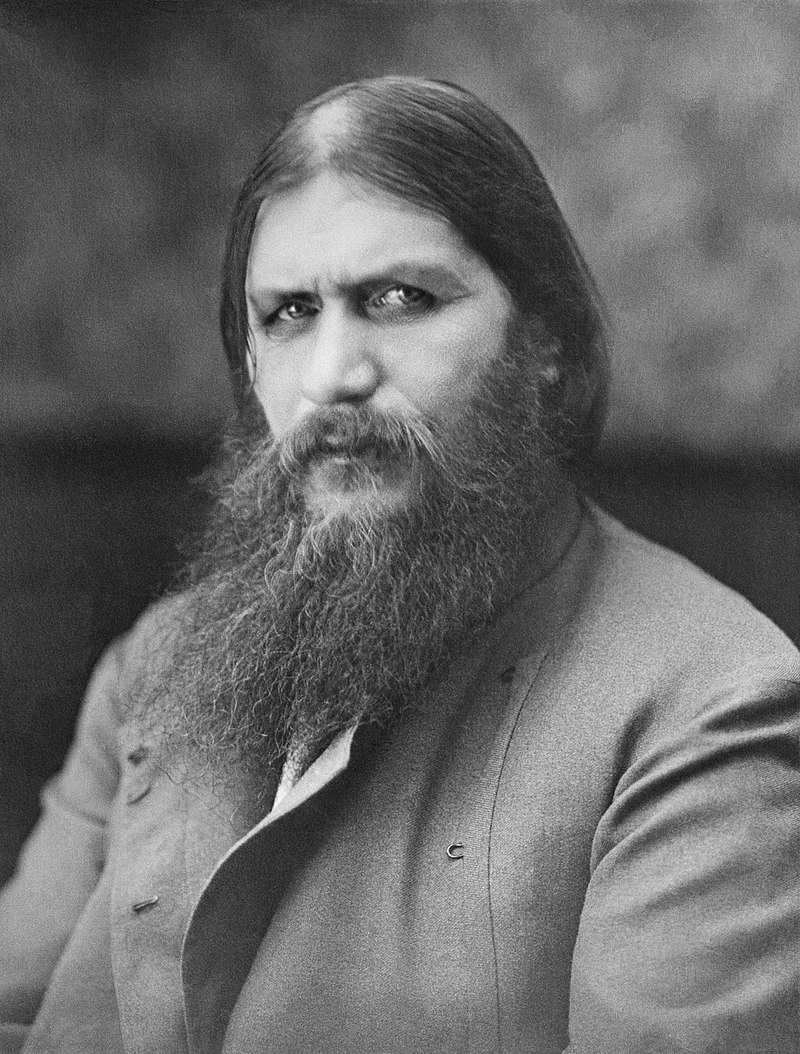

Alexander Danilovich Menshikov was a Russian statesman and military leader and a boyhood friend and favorite of Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia. He was born on November 16, 1673, in Moscow, Russia and his father Danil Menshikov died in 1695. There is no definite information on Menshikov’s origin. One colorful story says his Lithuanian peasant father apprenticed him to a pastry cook in Moscow where he attracted the attention of François Jacques Le Fort, a Swiss-born Russian admiral and close associate of Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia, who took him on as a servant.

However, it is almost certain that Danil Menshikov, Menshikov’s father, was a soldier who served under Alexei I, Tsar of All Russia, Peter I’s father, as a corporal-clerk stationed at Preobrazhenskoye, near Moscow, and was probably of Lithuanian origin. Alexis I partly resided at the imperial estate in Preobrazhenskoye and his son Peter I spent a good part of his childhood there. Alexander was seventeen months younger than Peter I and spent his childhood as a stable boy at the Preobrazhenskoye imperial estate. From a young age, Alexander understood that it was advantageous to be close to Peter I. He was one of the first boys to volunteer for Peter I’s poteshnye voiska, the Toy Army made up of Peter’s playmates, noblemen’s sons, and attendants at his father’s court. Alexander’s friendship with Peter I lasted until Peter I’s death in 1725.

Ten-year-old Peter I became co-tsar with his elder half-brother Ivan V in 1682. From childhood, Ivan had serious physical and mental disabilities and was never really able to participate in reigning. By the age of 27, Ivan was senile, paralyzed, and almost blind. He died February 8, 1696, at the age of 29, and his half-brother and co-ruler Peter I was left to be the sole Tsar of All Russia and after 1721, Emperor of All Russia.

Alexander painted in the Netherlands during the Grand Embassy of Peter the Great, by Michiel van Musscher,1698; Credit – Wikipedia

Alexander Menshikov joined the Preobrazhensky Regiment, formed by Peter I in 1687 from his poteshnye voiska (Toy Army), and participated in the Azov campaigns (1695 – 1696) against the Ottoman Empire. In 1697, Peter I traveled incognito to Western Europe on an 18-month tour called the Grand Embassy and Alexander accompanied him. In the Netherlands, Peter I and Alexander studied shipbuilding, skills later used to build the Russian navy. In England, Peter I and Alexander met with King William III, visited Greenwich and Oxford, and saw a Royal Navy Fleet Review. They traveled to Manchester, England to learn the techniques of city-building which would later be used to found the city of St. Petersburg.

Alexander married Princess Daria Mikhailovna Arsenyeva (1682 – 1728) and they had three children:

In 1702, Alexander Menshikov was created Count and Prince of the Holy Roman Empire by Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I. After an impressive defeat against the Swedish army in 1706, Peter I created Alexander a Prince of the Russian Empire. As Peter I’s close friend, Alexander had several influential positions:

- 1st Governor-General of St. Petersburg (1702–1724)

- Field Marshal of the Russian Imperial Army (1709–1728)

- Member of Governing Senate (1711–1728)

- 1st President of College of War (1717–1724)

- Member of Supreme Privy Council (1726–1728)

- Admiral of the Russian Imperial Navy (1726–1728)

- Generalissimo of the Russian Imperial Army (1727–1728)

Alexander Menshikov is responsible for introducing Peter I to his second wife. Marta Skowrońska and her five siblings were orphaned when their Polish parents died of the plague. She was sent to live with an uncle. At the age of 17, Marta was married to a Swedish dragoon named Johann Raabe during the Great Northern War (1700 – 1712). A few days after the wedding, Marta’s husband left with his regiment which departed for the war and was never heard of again. After her town was invaded by the Russian army, a maid or mistress of a Russian general, traveled back to the Russian court with the army. She became a member of Alexander Menshikov’s household, and Peter I met Marta while visiting Alexander. By 1704, Marta was well established in Peter’s household as his mistress. In 1705, she converted to Russian Orthodoxy from Roman Catholicism and took the name of Catherine (Ekaterina) Alexeievna. Peter I and Catherine married publically in 1712. Their daughters Anna Petrovna and Elizabeth Petrovna, the only ones of their twelve children who survived, were the bridal attendants. Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna (1708 – 1728), married Karl Friedrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, had one son Carl Peter Ulrich, the future Peter III, Emperor of All Russia, and died of childbirth complications. Her younger sister Grand Duchess Elizabeth Petrovna (1709 – 1762), who never married, reigned in Russia as Elizabeth, Empress of All Russia.

A number of times, in his various positions and situations, Alexander Menshikov abused his power even though he was well aware of the principles on which Peter I’s reforms were conducted and was Peter I’s right hand in all his endeavors. Alexander’s corrupt practices frequently brought him to the verge of ruin.

Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1718, Peter I’s son from his first marriage and his heir Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich was suspected of plotting to overthrow his father. Alexei was tried, confessed under torture, convicted, and sentenced to be executed. The sentence could be carried out only with Peters’s signed authorization, but Alexei died in prison because his father hesitated in making the decision. Alexei’s death most likely resulted from injuries suffered during his torture. Alexander Menshikov was likely complicit in all the decisions regarding Alexei.

Tsarevich Alexei’s only son Peter Alexeievich, born in 1715, had been ignored by his grandfather Peter I. However, when all the sons of Peter I and his second wife Catherine died there was a succession issue and little Peter received more attention. Besides his grandfather, Peter Alexeievich was the only living male Romanov. Peter I ordered Alexander Menshikov to find tutors for Peter Alexeievich. The tutors Alexander picked were of low quality for a reason – Alexander supported Peter I’s second wife Catherine as his successor.

During the last two years of his life, Peter I suffered from urinary tract problems. During his grandfather’s illness, Peter Alexeievich met Ivan Alexeievich Dolgorukov (1708 – 1739), his future favorite. Peter Alexeievich often visited the home of Alexei Grigoryevich Dolgorukov, Ivan Alexeievich’s father, where his rights to the Russian throne were explained to him. Peter Alexeievich vowed to crush the favorite of his grandfather, Alexander Menshikov, who led the opposition to the old noble families who had not been in favor of the Westernizing reforms of Peter I. However, there was strong opposition to Peter Alexeievich succeeding his grandfather.

Catherine I, Empress of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

On February 8, 1725, Peter I died at the age of 52 from a bladder infection without naming a successor. A coup arranged by Alexander Menshikov proclaimed Catherine, Peter’s second wife, the ruler of Russia. During the two-year reign of Catherine I, Empress of All Russia, the real power was held by Alexander and members of the Supreme Privy Council. Catherine I’s reign was only two years and even before her death, it was clear that the inheritance of Peter I’s grandson could not be denied. Alexander began to see this during the end of Catherine I’s reign. Through his efforts, Peter Alexeievich was named Catherine’s heir apparent, even though Catherine had two daughters. Catherine also gave her consent to the betrothal of Peter Alexeievich to Menshikov’s daughter Maria Alexandrovna.

On May 17, 1727, 43-year-old Catherine I, Empress of All Russia died of tuberculosis and 11-year-old Peter Alexeievich became Peter II, Emperor of All Russia. Alexander Menshikov took the young emperor into his home and had complete control over him. The old nobility, represented by the Dolgorukovs and the Galitzines, united to overthrow Alexander. He was deprived of all his dignities, offices, and wealth, expelled from St. Petersburg, and banished to Siberia with his wife and children. The Senate, the Supreme Privy Council, and the emperor’s guards took an oath of allegiance to Peter II, who reigned for only three years due to his death from smallpox.

Alexander and his three children in exile by Vasily Surikov, 1888; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1728, on the way to exile in Siberia, Alexander Menshnikov’s wife Daria Mikhailovna Arsenyeva died. Alexander, his three children, and their eight faithful servants settled into exile in Beryozovo, Siberia, Russia. Alexander built himself a house and a small church, and lived out his life with the philosophy, “I began with a simple life and will finish with a simple life.” During a smallpox epidemic in Siberia, Alexander Danilovich Menshikov died on November 23, 1729, aged 56. His elder daughter Maria also died during the smallpox epidemic. Alexander and his daughter Maria were buried at the altar of the church he had built.

In 1731, during the reign of Anna, Empress of All Russia, who succeeded Peter II, Alexander’s two remaining children were called back from exile. His daughter Alexandra married but died in childbirth delivering her first child who did not survive. His son Alexander Alexandrovich Menshikov married Princess Yelizaveta Petrovna Galitzina, had two sons and two daughters. Alexander Alexandrovich joined the Preobrazhensky Regiment, received some of his father’s goods back, distinguished himself in the Turkish and Swedish Wars, and died with the rank of General-in-Chief. Alexander Danilovich’s great-grandson Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov was the Russian Commander-in-Chief in the Crimean War.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. 2021. Alexander Danilowitsch Menschikow. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Danilowitsch_Menschikow> [Accessed 5 January 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Alexander Danilovich Menshikov. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Danilovich_Menshikov> [Accessed 5 January 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2018. Catherine I, Empress Of All Russia. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/empress-catherine-i-of-russia/> [Accessed 5 January 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2018. Peter I (The Great), Emperor Of All Russia. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/emperor-peter-i-the-great-of-russia/> [Accessed 5 January 2021].

- Flantzer, S., 2018. Peter II, Emperor Of All Russia. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/emperor-peter-ii-of-russia/> [Accessed 5 January 2021].

- Massie, Robert K. (1980). Peter The Great: His Life and World. New York, NY.: Alfred A. Knopf

- Ru.wikipedia.org. 2021. Меншиков, Александр Данилович. [online] Available at: <https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9C%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%88%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2,_%D0%90%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%80_%D0%94%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87> [Accessed 5 January 2021].