by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

Sophie Amalie Moth; Credit – Wikipedia

Sophie Amalie Moth was a longtime mistress of King Christian V of Denmark and Norway. She was born in Copenhagen, Denmark on March 28, 1654, one of the eight children and the youngest of the four daughters of Paul Moth and Ida Burenneus. Sophie Amalie’s father Paul Moth (link in German) was a physician. In 1651, due to some well-placed contacts, Paul Moth received a call to the court of King Frederik III of Denmark and Norway in Copenhagen, Denmark. Shortly thereafter, he became the personal physician of King Frederik III. He also supervised the education of King Frederik III’s heir Crown Prince Christian, the future King Christian V of Denmark and Norway. Sophie Amalie grew up at the Danish court with her siblings.

King Christian V of Denmark and Norway; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1667, Crown Prince Christian married Charlotte Amalie of Hesse-Kassel and between the years 1671 – 1687, the couple had seven children. Upon his father’s death in 1670, Crown Prince Christian succeeded him as Christian V, King of Denmark and Norway. Sophie Amalie’s relationship with King Christian V started shortly after he became king and it was arranged by Sophie Amalie’s mother.

Immediately, news of the relationship was spread throughout the Danish court. Although Christian V’s adultery caused an embarrassing situation for his wife, Queen Charlotte Amalie always made the most of her position as queen, both in her public life as well as in her private interactions with her husband. Sophie Amalie was also wise enough to treat Queen Charlotte Amalie with respect. She lived discreetly at court and never exerted influence besides asking for some favors for relatives, especially her brother Matthias Moth, who took advantage of the connection.

In 1677, Sophie Amalie was recognized as Christian’s official mistress and was created Countess of Samsøe. Between 1672 – 1682, Christian V and Sophie Amalie had six children who were all publicly acknowledged. Following the practice of his grandfather and father, Christian also gave his illegitimate children the surname Gyldenløve which means Golden Love. All the children also had Christian or Christiane among their names in honor of their royal father. The current Danish noble family of the Danneskiold-Samsøe descends from the eldest son of Sophie Amalie and King Christian V.

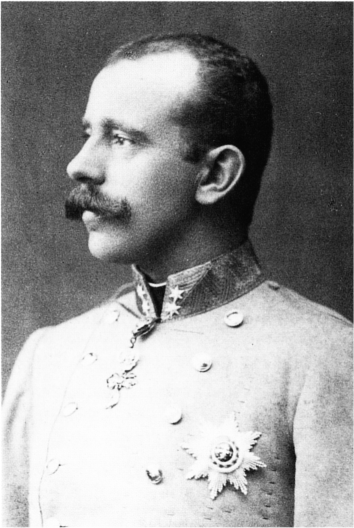

Christian Gyldenløve, eldest son of Sophie Amalie and Christian V; Credit – Wikipedia

Christian and Sophie Amalie had six children:

- Christiane Gyldenløve (link in Danish) (1672 – 1689), married Count Frederik Ahlefeldt (link in Danish), no children, died at age 17

- Christian Gyldenløve (1674 – 1703), married (1) Countess Charlotte Amalie of Danneskiold-Samsøe, daughter of an illegitimate son of King Frederik III, had two daughters (2) Dorothea Krag, had two sons

- Sophie Christiane Gyldenløve (1675 – 1684)

- Anna Christiane Gyldenløve (1676 – 1689)

- Ulrik Christian Gyldenløve (1678 – 1719), Danish Navy Admiral and Governor of Iceland

- A daughter (1682 – 1684)

Sophie Amalie and her children were financially secure because of the funds received from King Christian V and the crown treasury. King Christian V was an active participant in the children’s upbringing, education, and marriage negotiations. When his sons by Sophia Amalie reached the age of five or six, they were sent to be raised by King Christian V’s illegitimate half-brother Ulrik Frederik Gyldenløve, Count of Laurvig.

Sophie Amalie was able to purchase properties with the funds she had received. These properties further ensured the financial security of Sophie Amalie and her children. In 1682, Sophia Amalie received several properties in Gottorp from Christian V. After the death of naval hero Niels Jue in 1697, Sophia Amalie was given Thott Mansion, the mansion that Christian V had built for Juel. However, she immediately passed Thott Mansion on to her eldest son Christian Gyldenløve.

Jomfruens Egede; Credit – Af NPSE – Eget arbejde, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5789075

After the death of King Christian V in 1699, Sophie Amalie left the Danish court and retired to Jomfruens Egede, an estate she had purchased in 1674 in Fakse on the island of Zealand in eastern Denmark. Twenty years later, Sophie Amalie died on January 17, 1719, aged 64, at her home Jomfruens Egede. She was first buried at the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen, Denmark. In 1734, Sophia Amalie and her eldest son Christian Gyldenløve were reinterred at Saint Peter’s Church in Copenhagen, Denmark.

St. Peter’s Church in Copenhagen; Credit – By Tanya Dedyukhina, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56793710

Works Cited

- Da.wikipedia.org. 2020. Sophie Amalie Moth. [online] Available at: <https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophie_Amalie_Moth> [Accessed 1 May 2020].

- Dansk kvindebiografisk leksikon. n.d. Sophie Amalie Moth (1654 – 1719). [online] Available at: <https://www.kvinfo.dk/side/597/bio/1457/origin/170/> [Accessed 1 May 2020].

- De.wikipedia.org. 2020. Sophie Amalie Moth. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophie_Amalie_Moth> [Accessed 1 May 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Sophie Amalie Moth. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophie_Amalie_Moth> [Accessed 1 May 2020].

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.