by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

Born in the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia on April 22, 1847, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich was the third of the six sons and the fourth of the eight children of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia and Marie of Hesse and by Rhine (Empress Maria Alexandrovna). The most recognized claimant as the Head of the Imperial Family of Russia is through Vladimir’s line.

Vladimir had seven siblings:

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Alexandrovna (1842 – 1849), died of meningitis at the age of six

- Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich (1843 – 1865), engaged to Dagmar of Denmark (the future wife of his brother Alexander III), died of meningitis at the age of 21

- Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia (1845 – 1894), married Dagmar of Denmark (Maria Feodorovna), had issue

- Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich (1850 – 1908), had illegitimate issue via an affair with Alexandra Vasilievna Zhukovskaya

- Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna (1853 – 1920) married, Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, had issue

- Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich (1857 – 1905), married, Elisabeth of Hesse of Hesse and by Rhine (Elizabeth Feodorovna), no issue

- Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich (1860 – 1919), married (1) Alexandra of Greece and Denmark (Alexandra Georgievna), had issue (2) Olga Karnovich, had issue

Alexander II and his children (left to right) Maria, Alexander II, Sergei, Alexander III, Nicholas; (left to right, standing in back) Vladimir, Alexei (Paul is not in the photo); Credit – Wikipedia

At the time of his birth, Vladimir’s grandfather Nicholas I was the Emperor of All Russia. In 1855, when he was eight-years-old, Vladimir’s grandfather died and his father became Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia. Along with his brothers, Vladimir was well educated by Count Sergei Grigoryevich Stroganov who played a significant role in the development of Russian education during the nineteenth century. Vladimir showed an interest in the arts and literature but like all Romanov men, he was destined for a career in the military and he enlisted in the Preobrazhensky Regiment. Vladimir rose in rank until, in 1880, he was made General of the Infantry.

As the third son, Vladimir was considered distant from the throne but in 1865, the death of his eldest brother Tsesarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich at the age of 21 changed that. Vladimir was then the second in the line of succession after his elder brother Alexander, the future Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia, married and had sons.

Engagement Photo: Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Vladimir: Photo Credit – Wikipedia

In 1871, while traveling with his family through Germany, twenty-year-old Vladimir met his seventeen-year-old second cousin Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, the daughter of Friedrich Franz II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and his first wife Augusta of Reuss-Köstritz. Vladimir and Marie quickly fell in love and Marie broke off her engagement with Georg Albrecht, Prince of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt. However, Marie, who was Lutheran, refused to convert to Russian Orthodoxy. This caused a three-year delay in the marriage until Vladimir’s father Alexander II allowed Marie to remain Lutheran and ruled that Vladimir could still retain his succession rights. The engagement was announced in April 1874. The wedding was held at the Grand Church of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia on August 28, 1874, After marriage, the bride was known as Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna.

Marriage of Vladimir and Maria Pavlovna; Credit – Wikipedia

Vladimir and Maria had five children:

- Grand Duke Alexander Vladimirovich (1875 – 1877), died in early childhood

- Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich (1876 – 1938), married his first cousin Victoria Melita of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, had three children

- Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich (1877 – 1943), married (1919) his mistress Zinaida Rashevskaya, no children

- Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich (1879 – 1956), married (1921) his mistress, the famous ballerina Matilde Kschessinskaya (known as Princess Romanovskaya-Krasinskaya after her marriage), her son Prince Vladimir Romanovsky-Krasinsky could be the son of Andrei or his cousin Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich

- Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna (1882 – 1957), married Prince Nicholas of Greece, had three daughters including Princess Marina of Greece who married Prince George, Duke of Kent, son of King George V of the United Kingdom

Grand Duke Vladimir’s family in 1899, from left to right: Grand Duke Andrei, Grand Duke Vladimir, Grand Duchess Elena, Grand Duke Kirill, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, and Grand Duke Boris; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Vladimir and Maria moved into the new 360-room Vladimir Palace on the Palace Embankment facing the Neva River just down the road from the Winter Palace. The yellow facade of the palace is in the Florentine Renaissance style and the interior is a mixture of Moorish, Gothic and Rococo styles. It was the last imperial palace built in St. Petersburg. Across the Neva River was a view of the Peter and Paul Fortress and within the Fortress, the Peter and Paul Cathedral with its gilded spire with a flying angel at the very top. Vladimir and Maria enjoyed entertaining and Vladimir Palace became the heart of St. Petersburg’s social life. Today the building is the home of the Russian Academy of Science.

Vladimir Palace; Photo Credit – Von A.Savin (Wikimedia Commons · WikiPhotoSpace) – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21506331

On March 13, 1881, Vladimir’s father Alexander II fell victim to assassination when a bomb was thrown into his carriage. He asked to be returned to the Winter Palace to die. For 45 minutes, those in the room watched as Alexander II’s life ebbed away. Vladimir’s older brother succeeded Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia. Because he had retained his composure, Vladimir was the one to announce his father’s death to the public. The heir to the throne was Alexander III’s eldest son 13-year-old Nicholas (the future Nicholas II). Vladimir was appointed regent in the event of the death of Alexander III before Nicholas had reached the age of majority.

Always interested in the arts, Vladimir was a talented painter and had a valuable collection of ancient paintings and icons. He also had a great interest in ballet and financed ballet impresario Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev’s ballet troupe’s tour of Russia. Vladimir was appointed the president of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts and was a trustee of the Moscow Public Museum and Rumyantsev Museum. He presided over the commission for the construction of the beautiful Cathedral of the Savior on Spilled Blood, built on the site where his father Alexander II was fatally wounded by a bomb.

In 1894, Vladimir’s brother Alexander III became ill with nephritis, a kidney disorder. Alexander’s condition rapidly deteriorated and he died on November 1, 1894, at the age of 49. His 26-year-old son Nicholas became the last Emperor of All Russia, and married Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine (Alexandra Feodorova) just eight days after Alexander III was buried at the Peter and Paul Cathedral.

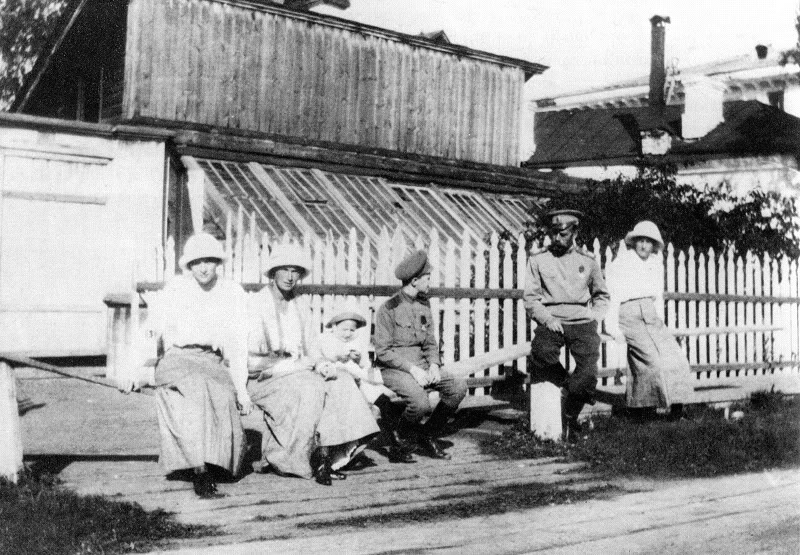

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna and Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

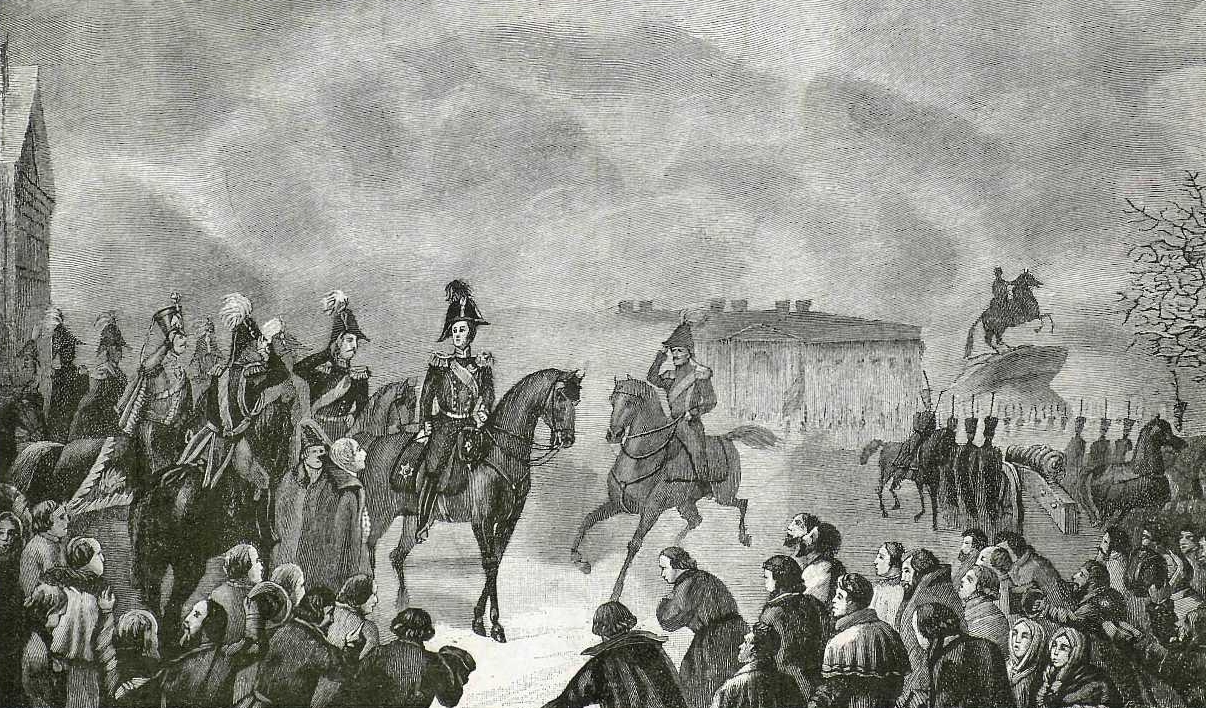

From 1884 – 1905, Vladimir served as commander-in-chief of the Preobrazhensky Guards and the St. Petersburg Military District. In January 1905, workers’ strikes broke out in St. Petersburg. On January 22, 1905, a peaceful procession of thousands of workers carrying religious icons and singing “God Save the Tsar” was led by a priest, Father Georgy Apollonovich Gapon. The workers marched towards the Winter Palace hoping to present their request for reforms directly to Emperor Nicholas II. However, Nicholas was at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, outside St. Petersburg.

The Preobrazhensky Guards were ordered to use military force to prevent the workers from reaching the Winter Palace. Official records showed 96 dead and 333 injured while anti-government sources claimed more than 4,000 dead. More moderate estimates are that 1,000 were killed or wounded, both from being shot and being trampled during the panic. It is unclear if Vladimir was the one who gave the order to use military force but nevertheless, his reputation was tarnished.

Bloody Sunday in 1905 by Wojciech Kossak; Credit – Wikipedia

The massacre, known as Bloody Sunday, was followed by a series of strikes in other cities, peasant uprisings, and mutinies in the armed forces, all of which seriously threatened the imperial regime and became known as the Revolution of 1905. A month after Bloody Sunday, Vladimir’s brother Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, Governor-General of Moscow, was killed by a terrorist bomb while driving in his carriage, just like his father Alexander II.

Later in 1905, Vladimir’s eldest son Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich married his first cousin, Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in Germany. Victoria Melita was the daughter of Prince Alfred of the United Kingdom, Duke of Edinburgh and Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (second son of Queen Victoria) and Vladimir’s sister Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia. Because Kirill married his first cousin, which was prohibited by the Russian Orthodox Church, and because he had not received the consent of Nicholas II to marry, he was stripped of his imperial titles, military appointments, and funding. The couple was banished from Russia and settled in France. Vladimir went into a rage after a brief interview with his nephew Nicholas II and resigned from all his posts in the army.

Grand Duke Vladimir; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

On February 17, 1909, 61-year-old Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich died suddenly at Vladimir Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia after suffering a major cerebral hemorrhage. Three days later, his body was transported from Vladimir Palace across the Neva River to the Peter and Paul Cathedral in the Peter and Paul Fortress. His funeral and burial, held on February 21, 1909, was attended by Nicholas II, Vladimir’s widow Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, other members of the Imperial Family, government ministers, and Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria. Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich was buried in the Grand Ducal Mausoleum, adjacent to the Peter and Paul Cathedral.

In 1909, following several deaths within the Imperial Family including Vladimir’s, Kirill was third in line to the Russian throne after Nicholas II’s hemophiliac son Alexei and Nicholas’ younger brother Michael. Nicholas II relented and allowed Kirill to return to Russia, restoring his Imperial titles, his military positions, and his funding. Following the abdication of Nicholas II in 1917, Kirill and his family left Russia. They settled first in Finland, before moving to Munich, Germany, and then Zurich, Switzerland. Eventually, they settled permanently in Saint-Briac, France.

Bolstered by a group of supporters and the laws of the former Imperial Family, under which Kirill was the rightful heir to the throne, Kirill declared himself Emperor of All Russia on August 31, 1924. This claim was later taken by his son Vladimir Kirillovich, and then by Vladimir Kirillovich’s only child Maria Vladimirovna, who declared herself Head of the Imperial House in 1992. Maria Vladimirovna is the most widely acknowledged claimant to the headship of the Imperial Family of Russia.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duke_Vladimir_Alexandrovich_of_Russia [Accessed 24 Feb. 2018].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2018). Vladimir Alexandrovitch de Russie. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Alexandrovitch_de_Russie [Accessed 24 Feb. 2018].

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2018). Владимир Александрович. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%92%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%B8%D0%BC%D0%B8%D1%80_%D0%90%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87 [Accessed 24 Feb. 2018].

- Unofficial Royalty. (2018). Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia. [online] Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/alexander-ii-emperor-of-all-the-russias/ [Accessed 24 Feb. 2018].

- Unofficial Royalty. (2018). Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia. [online] Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/grand-duke-kirill-vladimirovich-of-russia/ [Accessed 24 Feb. 2018].