by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

Credit – Wikipedia

The second wife of Paul I, Emperor of All Russia, Her Serene Highness Duchess Sophia Dorothea of Württemberg (Sophia Marie Dorothea Auguste Luise) was the eldest of the four daughters and the fourth of the twelve children of Friedrich II Eugen, Duke of Württemberg and Friederike Dorothea of Brandenburg-Schwedt. She was born on October 25, 1759, in Stettin, Kingdom of Prussia (now Szczecin, Poland), the same birthplace as her mother-in-law Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia. Sophia Dorothea’s father served in the Prussian army as did the father of Catherine the Great. Her mother was a niece of Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia.

Sophia Dorothea had eleven siblings. All but one survived to adulthood.

- Friedrich I, King of Württemberg (1754 – 1816), married (1) Augusta of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, had four children (2) Charlotte, Princess Royal, no children

- Ludwig (1756 – 1817), married (1) Maria Anna Czartoryska, divorced, had one son (2) Henriette of Nassau-Weilburg, had five children including Pauline who married her first cousin King Wilhelm I of Württemberg

- Eugen (1758 – 1822), married Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, had five children

- Wilhelm Friedrich Philip (1761 – 1830), married morganatically Wilhelmine, Freiin von Tunderfeld-Rhodis, had six children

- Ferdinand Friedrich August (1763 – 1834), married (1) Albertine of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, divorced, no children (2) Pauline von Metternich-Winneburg, no issue

- Friederike Elisabeth Amalie (1765 – 1785), married Peter Friedrich of Holstein-Gottorp, had two sons, died in childbirth

- Elisabeth Wilhelmine Luise (1767 – 1790), married Franz II, Holy Roman Emperor (later Emperor Franz I of Austria), had one child who died during childbirth along with Elisabeth

- Friederike Wilhelmine Katharina (born and died 1768)

- Karl Friedrich Heinrich (1770 – 1791)

- Alexander Friedrich Karl (1771 – 1833), married Antoinette of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, had five children including Marie who was the second wife of Ernst I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

- Karl Heinrich (1772 – 1833), married morganatically Christine Caroline Alexei, had five children

Sophia Dorothea in 1770; Credit – Wikipedia

After Sophia Dorothea’s father finished his military service, the family moved to Château de Montbéliard, a Württemberg castle in Montbéliard, France. Sophia Dorothea had a happy family life and was taught to be modest, disciplined, and religious. She was instructed in French, Italian, Latin, history, and geography. In addition, she was taught conversation, music, dance, drawing, painting, needlework, and housekeeping skills.

In 1773, when Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia was searching for a bride for her 18-year-old son and heir Grand Duke Paul Petrovich (the future Paul I, Emperor of All Russia), Sophia Dorothea was one of the possibilities but was eventually excluded because she was too young. Wilhelmine Luise of Hesse-Darmstadt (Grand Duchess Natalia Alexeievna) married Paul in 1773 but she died in childbirth in April 1776 along with her only child. In that same year, 16-year-old Sophia Dorothea was engaged to Ludwig of Hesse-Darmstadt who would become the first Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine and was the brother of Paul’s deceased first wife. Sophia Dorothea’s great-uncle Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia suggested she would make an ideal second wife for Grand Duke Paul. Catherine the Great, who had been born a German princess (Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst) in the same city as Sophia Dorothea and received a similar upbringing, thought it was a wonderful idea. The engagement to Ludwig of Hesse-Darmstadt was broken off and Ludwig received a monetary compensation.

In a meeting arranged by King Friedrich II of Prussia, Sophia Dorothea and Paul first met in Berlin, Prussia in June 1776. Through the efforts of Friedrich, the widowed Paul became reconciled to a second marriage and immediately liked Sophia Dorothea. The 16-year-old Sophia Dorothea was pleased with the prospect of becoming Empress of All Russia. She arrived in Russia in August 1776. On September 14, 1776, Sophia Dorothea converted from Lutheranism to Russian Orthodoxy and received the name Maria Feodorovna. The next day Maria was formally betrothed to Paul and was created a Grand Duchess of Russia. On October 7, 1776, less than six months after the death of Paul’s first wife, 17-year-old Maria Feodorovna and 22-year-old Paul Petrovich were married in St. Petersburg. The couple had a happy marriage for many years.

Grand Duke Paul, the future Emperor Paul I by Alexander Roslin; Credit – Wikipedia

Maria Feodorovna and Paul had ten children including two Emperors of All Russia. Only one of their children did not survive childhood.

- Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia (1777 – 1825), married Luise of Baden (Elizabeth Alexeievna), had two daughters who both died in childhood

- Grand Duke Konstantine Pavlovich (1779 – 1831), married (1) Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (Anna Feodorovna), no children, marriage annulled (2) Joanna Grudzińska, no children, a morganatic marriage that cost Constantine the crown

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna (1783 – 1801), married Archduke Joseph of Austria, Count Palatine of Hungary, had one daughter who died at birth, Alexandra died of childbirth complications a week later

- Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (1784 – 1803), married Friedrich Ludwig, Hereditary Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, had two children

- Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (1786 – 1859), married Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, had four children including Augusta who married Wilhelm I, German Emperor, King of Prussia

- Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna (1788 – 1819), married (1) Georg of Oldenburg, had two sons (2) King Wilhelm I of Württemberg, had two daughters including Sophie who married King Willem III of the Netherlands

- Grand Duchess Olga Pavlovna (1792 – 1795), died in early childhood

- Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna (1795 – 1865), married King Willem II of the Netherlands, had five children including King Willem III of the Netherlands

- Nicholas I, Emperor of All Russia (1796 – 1855), married Charlotte of Prussia (Alexandra Feodorovna), had ten children including Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia

- Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich (1798 – 1849), married Charlotte of Württemberg (Elena Pavlovna), had five children

The family of Maria Feodorovna and Paul in 1800; Credit – Wikipedia

The relationship between Paul and his mother had never been good. Paul had been taken at birth by his great-aunt Elizabeth I, Empress of All Russia, and raised under her supervision. Even after the death of Empress Elizabeth, Paul’s relationship with Catherine hardly improved. Paul’s early isolation from his mother created a distance between them which later events would reinforce.

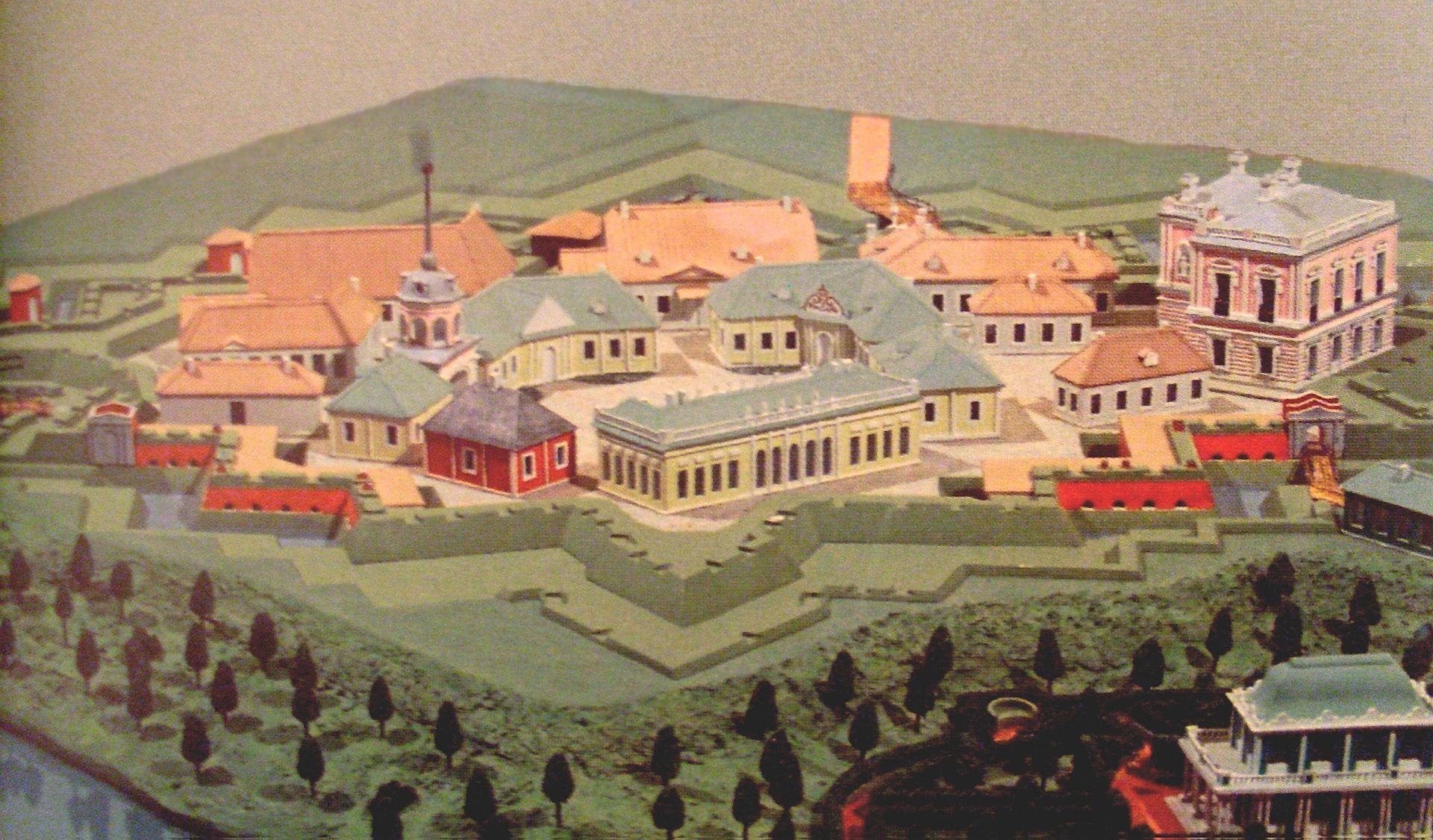

At first, Maria Feodorovna and Catherine had a good relationship but the situation deteriorated when Maria’s first child was born in 1777. Just as Empress Elizabeth had done to her, Catherine the Great took away Maria’s firstborn child Alexander to raise him without interference from his parents. When a second son, Constantine, was born in 1779, Catherine also took him away. Maria and Paul were allowed to visit their sons only once a week. As their reward for producing an heir to the throne, Maria and Paul were given Pavlovsk Palace near Tsarkoye Selo. All of Maria and Paul’s remaining children were allowed to stay with them but the couple had a great feeling of animosity toward Catherine. When their eldest daughter Alexandra was born, Catherine presented the couple with Gatchina Palace near St. Petersburg which had been built for Count Grigori Grigoryevich Orlov, who had been a favorite of Catherine.

The approach to Pavlovsk Palace in 1808 Gabriel Ludwig Lory; Credit – Wikipedia

Maria Feodorovna promoted the arts, painted watercolors, designed cameos, and created ivory artworks. She was a gifted musician, played the harpsichord, and arranged for plays to be performed at her court. Maria and Paul were particularly interested in German and French literature and created an extensive library of German works at Gatchina Palace where writers, artists, and scholars frequently gathered. Maria was instrumental in supporting the expeditions of Adam Johann von Krusenstern, a Russian admiral and explorer who led the first Russian circumnavigation of the world. She also supported welfare institutions and founded a mental institution in Saint Petersburg.

Catherine II (the Great) by Alexander Roslin, 1776; Credit – Wikipedia

Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia never considered inviting her son Paul to share her power in governing Russia. Once Paul’s son Alexander (the future Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia) was born, it appeared that Catherine had found a more suitable heir. It is possible that Catherine intended to bypass Paul and name her grandson Alexander as her successor but she never got the chance. On November 4, 1796, Catherine suffered a stroke. Despite all attempts to revive her, she fell into a coma from which she never recovered. Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia died on November 6, 1796, at the age of 67 and after a reign of 34 years. Paul was now Emperor of All Russia and Maria Feodorovna was Empress.

As Empress, Maria Feodorovna was more visible and was allowed to exert some political influence. She was responsible for the state welfare institutions and was a supporter of hospitals, soup kitchens, orphanages, and other facilities for the needy. Maria continued to promote the cultural life of Russia and personally supervised the beautification of imperial residences especially Gatchina Palace and the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg.

As Emperor, Paul agreed with the practices of autocracy and tried to prevent liberal ideas in the Russian Empire. He did not tolerate freedom of thought or resistance against autocracy. Because he overly taxed the nobility and limited their rights, the Russian nobles, by increasing numbers, were against him. Paul’s reign was becoming increasingly despotic. Eventually, the nobility reached their breaking point. As early as the end of 1797, rumors began swirling of a coup d’état being prepared by the nobility. It is probable that Paul’s son and heir Alexander knew of the coup d’état plans and that Maria Feodorovna knew about the existence of plans.

Afraid of intrigues and assassination plots, Paul disliked the Winter Palace where he never felt safe so he had the fortified Mikhailovsky Castle built in Saint Petersburg. In February 1801, Paul and his family moved into Mikhailovsky Castle. On the night of March 23, 1801, only forty days after moving into the castle, a group of conspirators charged into Paul’s bedroom, forced him to abdicate, and then strangled and trampled him to death. Paul’s eldest son, who probably knew about the coup but not the murder plot, succeeded as Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia.

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna in mourning by Gerhard von Kügelgen, 1801; Credit – Wikipedia

After Paul’s death, Maria Feodorovna made her home at Pavlovsk Palace. She demanded recognition as the highest-ranking woman in Russia and took precedence over Alexander I’s wife Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna. Sadly, Maria was similarly hurtful to her daughter-in-law as Catherine the Great had been to her. Maria’s charitable work, which started under the reign of her husband, continued during her widowhood. Although Maria Feodorovna was unable to make direct political decisions, she did have a great influence on her son Alexander as well as on her other children.

Maria Feodorovna actively participated in the marriage arrangements of her younger children with members of European royal families. The current Dutch royal family are her descendants. Although Maria had not been allowed to make decisions regarding the education of her two eldest sons, she did so with her two younger sons and influenced them in their conservative sentiments. When Alexander I died in 1825 and Nicholas I, who was 19 years younger than Alexander, became the new Emperor, his reign was politically conservative and extremely reactionary.

Empress Maria Feodorovna lived long enough to see the first three years of the reign of her third son Nicholas I, Emperor of All Russia. She outlived five of her ten children, dying at Pavlovsk Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia on November 5, 1828, at the age of 69 after a short illness. Maria Feodorovna was buried at the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg.

Tomb of Empress Maria Feodorovna; Photo Credit – Автор: El Pantera – собственная работа, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36433080

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Romanov Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Tsardom of Russia/Russian Empire Index

- Romanov Births, Marriages and Deaths

- Romanov Burial Sites

- Romanovs Killed During the Russian Revolution

- Romanovs Who Survived the Russian Revolution

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. (2018). Sophie Dorothea von Württemberg. [online] Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophie_Dorothee_von_W%C3%BCrttemberg [Accessed 25 Jan. 2018].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg). [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Feodorovna_(Sophie_Dorothea_of_W%C3%BCrttemberg) [Accessed 25 Jan. 2018].

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1981). The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias. New York, NY.: Doubleday

- Massie, R. (2016). Catherine the Great. London: Head of Zeus.

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2018). Мария Фёдоровна (жена Павла I). [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%8F_%D0%A4%D1%91%D0%B4%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%B0_(%D0%B6%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B0_%D0%9F%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%BB%D0%B0_I) [Accessed 25 Jan. 2018].