by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

Credit – Wikipedia

Her Highness Marie Sophie Frederikke Dagmar of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, known as Princess Dagmar and called Minnie in her family, was born at the Yellow Palace in Copenhagen, Denmark on November 26, 1847. She was the fourth child and the second daughter of Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg and Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel. In 1852, Prince Christian became heir to the Danish throne and in 1853 he was given the title Prince of Denmark and his children then became Princes and Princesses of Denmark. Christian succeeded to the Danish throne in 1863 and reigned as King Christian IX.

Minnie had five siblings:

- King Frederik VIII of Denmark (1843 – 1912), married Princess Louise of Sweden, had issue

- Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1844 – 1925), married King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, had issue

- Prince Vilhelm of Denmark, who became King George I of Greece (1845 – 1913), married Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna of Russia, had issue

- Princess Thyra of Denmark (1853 – 1933), married Crown Prince Ernest Augustus of Hanover, 3rd Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale, had issue

- Prince Valdemar of Denmark (1858 – 1939), married Princess Marie of Orléans

Family of King Christian IX; Back Row: Frederik, King Christian, and William; Front Row: Dagmar, Valdemar, Queen Louise, Thyra, and Alexandra; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Minnie grew up in a close and happy family environment. Her parents put an emphasis on giving their children a simple upbringing but attached great importance to their royal duties. As adults, all their children were known for their ability to deal with people, their sense of duty, and their ability to represent their royal families. Minnie was closest to her elder sister Alexandra and the two had close ties to each other for life.

Minnie with her first fiancé Nicholas Alexandrovich, Tsarevich of Russia, 1864; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Emperor Alexander II of Russia was searching for a bride for his eldest son and heir Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich from countries other than small German states that had traditionally provided brides for the Romanovs. In 1864, Nicholas Alexandrovich went to Denmark and proposed to Minnie. Nicholas Alexandrovich suffered from poor health and died from meningitis on April 24, 1865. Reportedly, his last wish was for Minnie to marry his brother Alexander Alexandrovich, the future Emperor Alexander III. Minnie had already started receiving instruction in the Russian language and preparing for her conversion to the Russian Orthodox religion.

Engagement Photo: Alexander and Minnie; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

In June 1866, while on a visit to Copenhagen, Denmark, Alexander proposed to Minnie, his deceased brother’s fiancée. Minnie converted to Russian Orthodoxy and received the name Maria Feodorovna. Alexander and Minnie were married on November 9, 1866, in the Imperial Chapel of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. After the wedding festivities, the newlyweds moved into the Anichkov Palace in St. Petersburg where they were to live for the next 15 years. In addition, they spent time at their summer villa Livadia Palace in the Crimean Peninsula.

Wedding of Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich & Maria Feodorovna by M.Zichy 1867, Hermitage; Credit – Wikipedia

Alexander and Minnie had six children:

- Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia (1868 – 1918), married Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine (Alexandra Feodorovna), had five children

- Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich (1869 – 1870), died young of meningitis

- Grand Duke George Alexandrovich (1871 – 1899), unmarried, died of tuberculosis

- Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna (1875 – 1960), married Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich of Russia, had seven children

- Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (1878 – 1918), married Natalia Sergeyevna Sheremetyevskaya, Countess Brasova, had one child

- Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna (1882 – 1960), married (1) Peter Friedrich Georg, Duke of Oldenburg, no children; (2) Nikolai Kulikovsky, had two children

Alexander, Minnie and their children in 1888, Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Minnie was a popular member of the Russian Imperial Family. She rarely mingled in politics, but instead devoted herself to her family, charities, and social activities. Among the charities she worked with were the Russian Red Cross and several educational institutions, including the famous Smolny Institute for Noble Maidens. Like her sister Alexandra, Princess of Wales, Minnie was anti-German because of the annexation of the previously Danish-owned Schleswig-Holstein duchies to Prussia in 1864. In the early years of their marriage, Minnie and Alexander settled into the huge Anichkov Palace on St. Petersburg’s main street, Nevsky Prospekt. The couple traveled around the Russian Empire and also regularly attended family get-togethers in Denmark.

On March 13, 1881, Alexander’s father, Alexander II, was assassinated in St. Petersburg, a victim of a bombing by the underground organization, Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will), and Alexander succeeded to the Russian throne. Security was tightened and Minnie and Alexander had to move out of St. Petersburg to Gatchina Palace, 28 miles away from St. Petersburg, which provided greater protection. Alexander and Minnie’s traditional coronation in the Kremlin in Moscow was held in strict security because a dangerous conspiracy had been discovered.

The Imperial Family was always heavily guarded, but Minnie often went to St. Petersburg to participate in and organize balls, receptions, and other things that she had enjoyed doing as a Grand Duchess. Minnie supported Alexander in his extreme conservative ideas. She sought to encourage foreign policy that favored Denmark and not Germany. In addition, she tried to get Russia to develop relations with the United Kingdom, two countries that traditionally were not allied.

Alexander and Dagmar’s visits to Denmark were always big events. The couple enjoyed being in Denmark because the atmosphere was more relaxed and they were under less stringent security than they were accustomed to in Russia. In 1885, during a Danish royal family dinner at Fredensborg Palace, Alexander announced that he would like to have his own home in Fredensborg. He bought a house near the castle grounds called Svalereden, but it became known as Kejserens Villa or Emperor’s Villa. Minnie held ownership of the home until her death in 1928 when her daughter Olga sold the house.

Family Get-Together at Fredensborg Palace in Denmark, 1889. (l-r): Top row: King Haakon VII of Norway; Emperor Nicholas II of Russia; Prince Nicholas of Greece and Denmark; Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia; Princess Victoria of the United Kingdom; King Christian X of Denmark; King Frederik VIII of Denmark; Queen Louise of Denmark; King Constantine I of Greece; Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia; Prince George of Greece and Denmark; Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom; Emperor Alexander III of Russia; Princess Maria of Greece and Denmark; Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna of Russia; King Christian IX of Denmark; Prince Harald of Denmark; Queen Maud of Norway; Middle row sitting: Prince Andrew of Greece; Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia; Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia; Queen Louise of Denmark; King George I of Greece; Princess Alexandra of Greece; On their knees on the grass: Princess Thyra of Denmark and Princess Ingeborg of Denmark; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

In 1894, Alexander became ill with nephritis, a kidney disease. Later that year, Alexander was on his way to the Greek isle of Corfu where he hoped to recuperate at Mon Repos, the villa of Minnie’s sister-in-law, Queen Olga of Greece. However, when Alexander reached Crimea, he was too ill to continue traveling and stayed at Livadia Palace, his home in Crimea. It was soon obvious that Alexander would not survive and various relatives came to the Crimea including Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, who was the fiancée of Alexander’s eldest son Nicholas. Insisting on receiving Princess Alix in his full dress uniform, Alexander gave her his blessing on October 21, 1894. Thereafter, Alexander’s condition rapidly deteriorated and he died on November 1, 1894, at the age of 49. His son Nicholas became the last Emperor of Russia and married Princess Alix (Alexandra Feodorovna) on Minnie’s 47th birthday, November 26, 1894, just eight days after Emperor Alexander III was buried at the Peter and Paul Cathedral at the Fortress of Peter and Paul in St. Petersburg.

During the early years of her son’s reign, Emperor Nicholas II often sought the advice of his mother. For a time after his accession and his marriage, he lived with her in Anichkov Palace. According to Russian custom, Minnie was still the country’s first lady, and this caused some strain between Minnie and her daughter-in-law Empress Alexandra. The two never got close to each other, and their relationship was the subject of much gossip. Minnie was more popular than the daughter-in-law and enjoyed her continued role as the first lady.

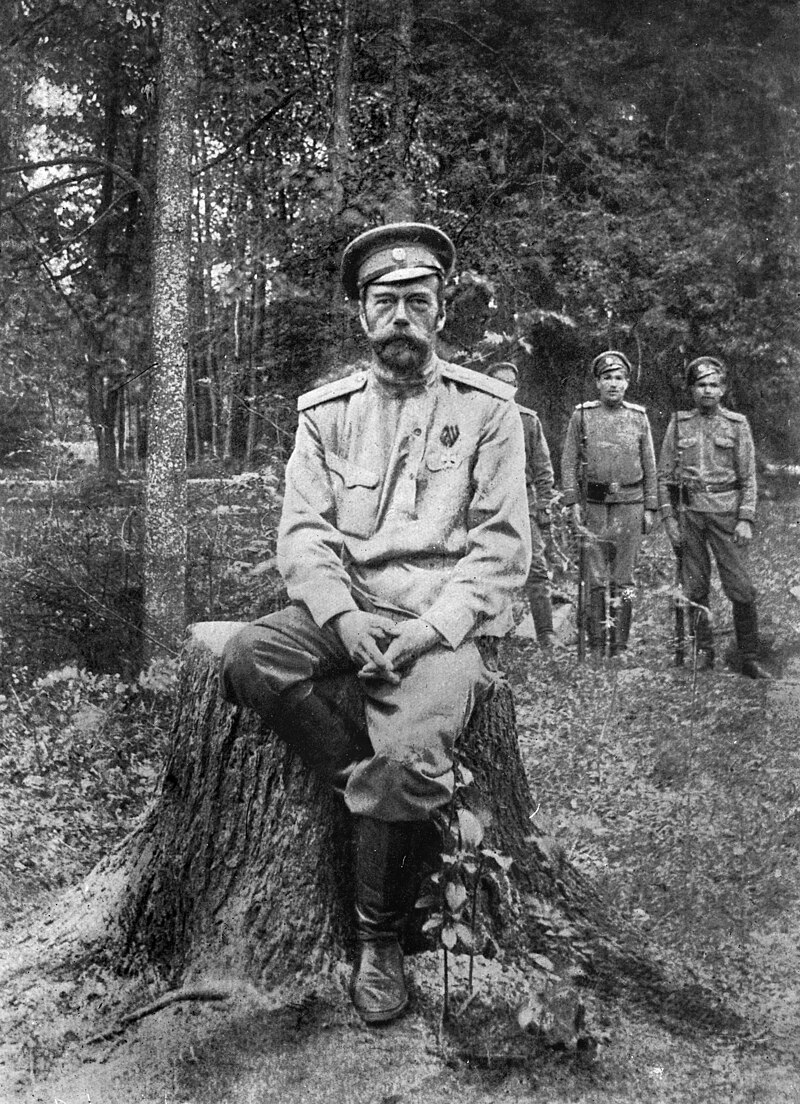

Emperor Nicholas II and his mother Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna in 1896; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Minnie’s political views changed as discontent and revolutionary events increased in Russia. She thought that some of the autocratic political power should be transferred to a more democratic, representative government and that Russia should look more to the West. However, Nicholas II retained his absolute power and eventually, Minnie’s role as a political adviser to her son disappeared, and Nicholas instead leaned more on his wife.

When the Russian Revolution broke out during World War I in 1917, Minnie was in Kyiv (now in Ukraine). After Nicholas abdicated, she saw him one last time, and after some reflection, she went to the Crimea where members of the Imperial Family had several summer homes. Here she witnessed the October Revolution later that year, and then in 1918 came the news of the murder of her son and his family, which she did not believe. Being in Crimea became precarious due to food shortages, visits to the home by the Bolshevik officials, and the threat of being murdered by the Bolsheviks.

The Romanovs under house arrest in Crimea in 1918. Standing: Colonel Nikolai Kulikovsky, Mr. Fogel, Olga Konstantinovna Vasiljeva, Prince Andrei Alexandrovich. Seated: Mr. Orbeliani, Prince Nikita, Grand Duchess Olga, Grand Duchess Xenia, The Dowager Empress (Minnie), and Grand Duke Alexander. On the floor: Prince Vasili, Prince Rostislav, and Prince Dmitri

Although the monarchy was abolished by the Russian Revolution, Minnie did not initially leave Russia. She finally fled in 1919 to London when her nephew King George V of the United Kingdom sent the warship HMS Marlborough to retrieve his aunt when she could no longer stay in Crimea. Rescued along with Minnie were 25 other Romanovs and/or their relatives.

Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich and Empress Maria Feodorovna escaping aboard the British battleship HMS Marlborough; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

After a short stay in London, Minnie returned home to her native Denmark where she briefly lived with her nephew King Christian X in a wing of the Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen. Minnie then decided to live at Hvidøre, the holiday villa she had purchased with her sister Alexandra in 1906, near Copenhagen.

Minnie and Alexandra at Hvidøre, circa 1910; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Minnie’s last years were overshadowed by the many deaths in her immediate family and she still refused to believe in the massacre of her son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren. Minnie died on October 13, 1928, at Hvidøre. Following services in Copenhagen’s Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Church, Minnie was interred in the crypt of the Christian IX Chapel at Roskilde Cathedral, the traditional burial place of the Danish royal family in Roskilde, Denmark.

First burial place of Empress Maria Feodorovna in Roskilde Cathedral; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Minnie had wished that at some point in time, she could be buried with her husband. In 2005, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed, along with their governments, that Minnie’s wish should be fulfilled. Minnie’s remains were transported to St. Petersburg. Following a service at Saint Isaac’s Cathedral, she was interred next to her husband Emperor Alexander III in the Peter and Paul Cathedral on September 28, 2006.

Tomb of Empress Maria Feodorovna; Photo Credit – Susan Flantzer, August 2011

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Romanov Resources at Unofficial Royalty