by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2017

Emperor Naruhito of Japan and Masako Owada were married on June 9, 1993, at the Kashiko-dokoro, the Shinto shrine of Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, on the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, Japan.

Photo Credit – Imperial Household Agency

Emperor Naruhito’s Background

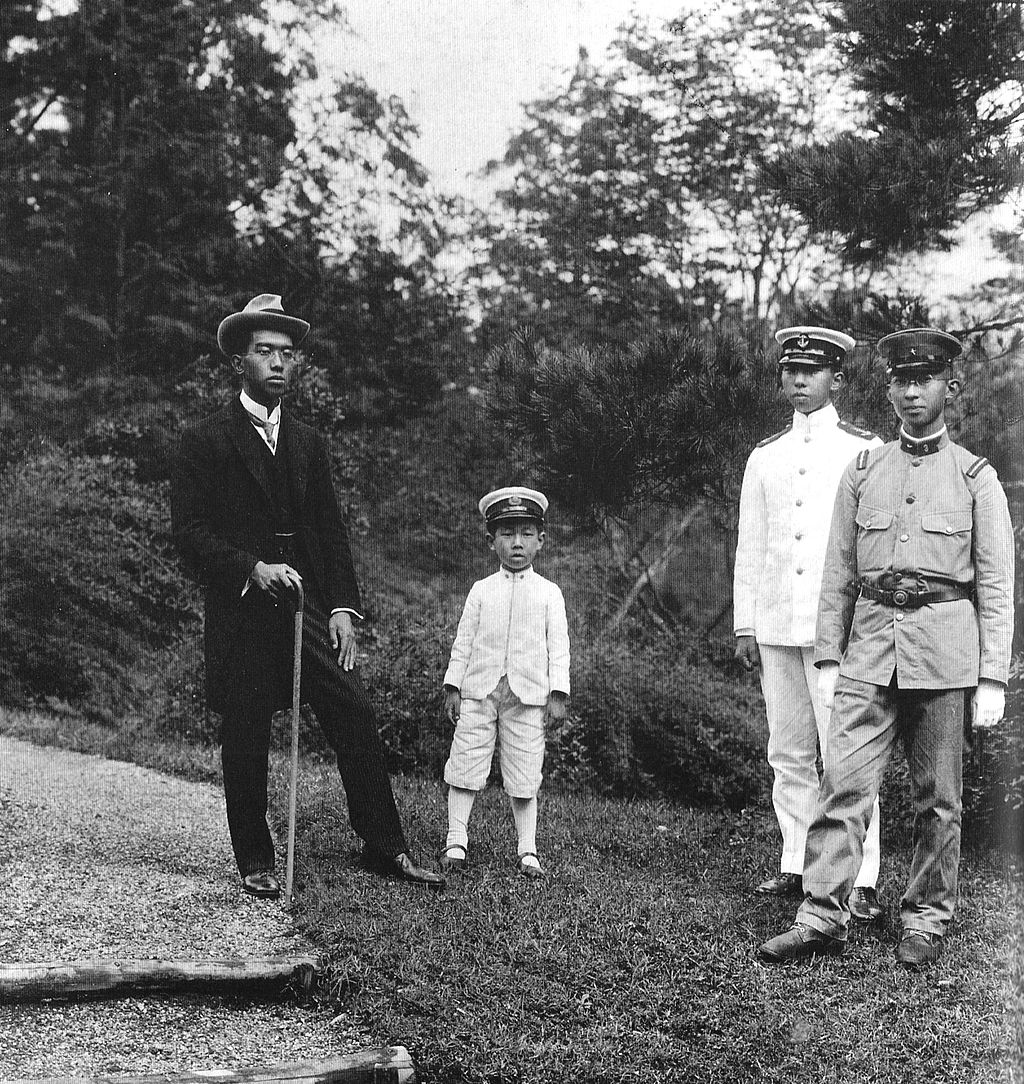

Naruhito, in the middle, with his family

The eldest son of Emperor Akihito of Japan and Michiko Shōda, Emperor Naruhito of Japan was born on February 23, 1960, at the Tokyo Imperial Palace. Born during the reign of his grandfather Emperor Hirohito, Naruhito was second in line to the throne. He has a younger brother, Prince Akishino (born 1965), and a younger sister, Mrs. Sayako Kuroda, the former Princess Nori (born 1969).

Naruhito was educated at the Gakushūin (or Peers School) in Tokyo from the age of four and went on to earn his Bachelor’s Degree in History from Gakushūin University in 1982. He then studied at Merton College at Oxford University in the United Kingdom before returning to Gakushūin University where he earned his Master’s Degree in history in 1988.

In January 1989, Naruhito’s grandfather died and his father became Emperor of Japan. Naruhito was invested as Crown Prince of Japan on February 23, 1991. Upon the abdication of his father, Naruhito became Emperor of Japan of May 1, 2019.

Masako Owada’s Background

Masako Owada was born in Tokyo on December 9, 1963, the eldest daughter of Hisashi Owada and Yumiko Egashira. Her father, a former Japanese diplomat, served as Japanese Ambassador to the United Nations and as a member of the International Court of Justice in the Netherlands. Masako has two younger twin sisters, Setsuko and Reiko, born in 1966.

Due to her father’s diplomatic posts, Masako began her schooling first in Moscow, and then in New York City, before the family returned to Japan in 1971. She attended Futaba Gakuen, a private Roman Catholic girls’ school in Tokyo. In 1979, the family returned to the United States, settling in Belmont, Massachusetts while her father was a visiting professor at Harvard University. She graduated from Belmont High School in 1981 and enrolled at Radcliffe College, part of Harvard University. She graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in economics in 1985, after which she returned to Japan and attended the University of Tokyo, studying law for several months while preparing to sit for the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs entrance exam. After two years working for the Foreign Ministry, she enrolled at Balliol College, Oxford University, pursuing a Master’s Degree in International Relations. Besides speaking Japanese, Masako is fluent in English, German, and French.

The Engagement

On the day of the engagement ceremony

Naruhito first met Masako Owada in November 1986, while she was a student at the University of Tokyo, at a tea for Infanta Elena of Spain. Naruhito was immediately captivated by Masako and arranged for them to meet several times over the next few weeks. Despite the Imperial Household Agency’s disapproval of Masako and Masako attending Balliol College, Oxford for the next two years, Naruhito remained interested in Masako.

Naruhito proposed to Masako twice, but she refused to marry him because it would force her to give up her career in diplomacy and severely restrict her independence and freedom. Finally, on December 9, 1992, Masako’s 29th birthday, she accepted Naruhito’s third proposal. Naruhito had argued that serving as Crown Princess of Japan would be another form of diplomacy. The Imperial Household Council formally announced the engagement on January 19, 1993, and the engagement ceremony (Nosai-no-Gi) was held at Masako’s parents’ home on April 12, 1993.

Engagement ceremony (Nosai-no-Gi) at Masako’s parents’ home; Photo Credit – Imperial Household Agency

On the morning of April 12, 1993, an imperial van arrived at Masako’s family home carrying traditional, plainly wrapped gifts: two enormous fish (tai or red sea bream), six bottles of sake, and five bolts of silk. The fish were laid out head to head, at a slight angle to each other, forming the lucky symbol of the number eight, which is supposed to bring prosperity to the couple. Two simple but elegant unpainted wood boxes carried the other presents, the six bottles of sake, and the five bolts of silk which would be made into evening gowns for the future princess.

Hiroo Kanno, Grand Master of the Crown Prince’s Household, presented the gifts along with the formal request of marriage. “Today, Crown Prince Naruhito presents imperial betrothal gifts to confirm his pledge of marriage with the consent of the Emperor and Empress,” said Hiroo Kanno. Masako Owada responded, according to the tradition, “I accept humbly.”

Masako, wearing a yellow outfit, then paid a visit to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, along with her parents. Her father Hisashi Owada, who at the time was Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, wore a morning coat and her mother wore a traditional kimono.

The Wedding Attire

On the morning of the wedding, Masako’s body was purified in an ancient ritual. Next, court ladies dressed her in the formal bridal attire, the juni-hitoe, which literally means twelve-layered garment. The 30-pound silk kimono with a white silk brocade train took three hours to put on and cost more than $300,000. Masako’s hair was arranged in classic style with long, artificial strands added down her back.

Naruhito wore a flowing robe of bright orange representing the rising sun which by tradition only a crown prince can wear. Both the bride and groom’s costumes dated back to the Heian Era (794-1185).

The Wedding Ceremony

The Three Palace Sanctuaries at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo; Photo Credit – Imperial Household Agency

Emperor Naruhito of Japan, then the Crown Prince, and Masako Owada were married on June 9, 1993, at the Kashiko-dokoro, the Shinto shrine of Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess and mythological ancestress of the Imperial Family, part of the Three Palace Sanctuaries on the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, Japan. 800 guests were invited, including Imperial Family members, the bride’s relatives including her parents, government officials, lawmakers, judges, and industrial leaders. Very few friends of the bride and groom were invited and no foreigners were invited. The groom’s parents, Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko, were not among the 800 guests. They stayed in their imperial sitting room a few hundred yards from the shrine and waited until midafternoon when the newlyweds visited them to inform them of the morning marriage. Guests did not actually attend the wedding ceremony. They stood in the Imperial Garden for the 10 AM wedding and only saw the bride and groom, accompanied by Shinto ritualists, chamberlains, and ladies-in-waiting, as they walked slowly down a long wooden porch.

The wedding ceremony took fifteen minutes and was not only out of the sight of the guests but also out of the sight of the millions of television viewers. In the inner sanctuary of the shrine and in the presence of only the palace’s chief Shinto ritualist, a chamberlain bearing the centuries-old sword representing the crown prince, a court lady and an unwed priestess symbolizing purity, Naruhito and Masako were married in the Kekkon-no-gi ceremony before an altar enshrining the Sun Goddess, the guardian of the Imperial Family.

Although the palace’s chief ritualist, an important figure in the Shinto religion, was present inside the shrine, the prince was the only person who did any speaking. Naruhito read from a 1,200-year-old text, addressing the Sun Goddess: “This is the occasion of my wedding, and we have come before you at the House of Wisdom…We pray for your protection in the future.” Then the chief ritualist waved a sacred dogwood sprig and the couple sipped sake from thimble-sized cups and bowed to each other. After the ceremony Naruhito and Masako went to the Kōrei-den, the Ancestral Spirits Sanctuary, another of the Three Palace Sanctuaries, where the departed spirits of the Imperial Family are enshrined one year after their death, to report the wedding to Naruhito’s imperial ancestors. The couple emerged from the shrine for another solemn procession down the wooden porch as husband and wife.

In the afternoon, Masako, in a formal white gown and diamond tiara, and Naruhito, also in formal Western attire, met with Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko at the Imperial Palace in a ceremony known as Choken-no-Gi (First Audience Ceremony). In the ancient ceremony, Naruhito, Masako, the Emperor, and the Empress were given chopsticks but no food and pantomimed the act of eating together.

Large crowds lined the 2.6-mile route to the couple’s home in the Tōgū Palace in central Tokyo. There, at 6:00 PM, Naruhito and Masako shared their first meal together as a married couple. Three hours later the couple participated in another ritual, the Kyutyu-Shukuen-no-Gi (Celebratory Banquet) in which rice cakes are offered along with prayers for the birth of a healthy boy. The Kyutyu-Shukuen-no-Gi (Celebratory Banquet) occurred for three nights. Each night, the couple received pounded rice cakes known as mochi. They ate some of the rice cakes and then buried the rest in the Imperial Garden, while the priests chanted prayers for the new Crown Princess to have children.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- “Crown Prince Naruhito Married Commoner Masako Owada Wednesday In…”. UPI. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2017.

- “Crown Prince Naruhito Of Japan”. Unofficial Royalty. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2017.

- “Crown Princess Masako Of Japan”. Unofficial Royalty. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2017.

- DAVID E. SANGER. “Royal Wedding In Japan Merges The Old And New”. Nytimes.com. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2017.

- JAMES STERNGOLD. “With Fishes, Sake And Silk, Japan’s Prince Plights His Troth”. Nytimes.com. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2017.

- “Masako, Crown Princess Of Japan”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2017.

- “Naruhito, Crown Prince Of Japan”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2017.

- Reid, T.R., and T.R. Reid. “MARRIAGE, JAPANESE STYLE”. Washington Post. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 May 2017.