by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

by Jens Juel, 1769; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1751, Frederick, Prince of Wales, heir to the throne and son of King George II of Great Britain, died at the age of 44. He left eight children, including the future King George III, and a pregnant wife, Augusta of Saxe-Coburg-Altenburg. Four months later, on July 22, 1751, at Leicester House in London, England, Princess Caroline Matilda of Wales was born.

Caroline Matilda had eight older siblings:

- Princess Augusta, Duchess of Brunswick (1737 – 1813) married Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, had issue

- King George III of the United Kingdom (1738 – 1820) married Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, had issue

- Prince Edward, Duke of York (1739 – 1767) died aged 28, unmarried

- Princess Elizabeth Caroline of Wales (1740 – 1759) died aged 18, unmarried

- Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester (1743 – 1805) married Maria, Countess Waldegrave, had issue

- Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland (1745 – 1790) married Anne Luttrell, no issue

- Princess Louisa (1749 – 1768) died aged 19, unmarried

- Prince Frederick (1750 – 1765) died aged 15, unmarried

Family of Frederick, Prince of Wales painted in 1751 after the prince’s death; Photo Credit – Wikipedia Front row: Henry, William, Frederick; Back row: Edward, George, Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales holding Caroline Matilda, Elizabeth, Louisa

The new princess was christened Caroline Matilda, Caroline after her late paternal grandmother Caroline of Ansbach and Matilda after her Norman and Angevin ancestors, on August 1, 1751, at Leicester House in London by Thomas Hayter, Bishop of Norwich. She was called by both her names to avoid confusion with her paternal aunt, who was one of her godparents.

Caroline Matilda’s godparents:

- George, Prince of Wales (her eldest brother, later King George III)

- Princess Caroline of Great Britain (her paternal aunt)

- Princess Augusta of Wales (her eldest sister, later Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel)

Caroline Matilda, age three by Jean-Etienne Liotard, 1754; Credit – Wikipedia

Caroline Matilda, considered the most attractive of the four sisters, was educated with her elder sister by two years, Louisa. While Caroline Matilda loved being outdoors and riding, Louisa suffered from poor health and eventually died of tuberculosis at the age of 19. Caroline Matilda was well educated, as were all her siblings, and could speak French, German, and Italian. Her two eldest brothers George and Edward moved out of Leicester House to their own household when Caroline Matilda was five years old. Her sister Elizabeth, who also suffered from delicate health like Louisa, died in 1759 at the age of 18.

In 1760, Caroline Matilda’s grandfather King George II died and her brother succeeded to the throne as King George III. In 1764, her eldest sister Augusta married Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, and left for her new home. Certainly, Caroline Matilda knew that royal children did not marry for love and that only unmarried princesses such as her paternal aunts Princess Amelia and her godmother Princess Caroline stayed home in England. She certainly saw what it was like for Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, her brother George’s 17-year-old bride, when she arrived in England alone, terrified, and unable to speak English.

Caroline Matilda (seated) and her sister Louisa by Francis Coates, 1767; Credit – Wikipedia, from The Royal Collection

Another of Caroline Matilda’s paternal aunts, Princess Louisa, had married King Frederik V of Denmark and Norway. Louisa had given birth to five children in five years before her death at age 27 due to complications from a miscarriage. In 1766, Caroline Matilda’s 17-year-old first cousin succeeded to the Danish throne as King Christian VII after the early death of his father. Since there was a connection between the British and Danish royal families and both families were Protestant, it was natural that a British bride should be sought for Christian. Even before the death of King Frederik V, negotiations for such a marriage were started. The preferred choice for a bride was initially Caroline Matilda’s sister Princess Louisa, but when the Danish representative in London heard of her ill health, Caroline Matilda became the prospective bride. The betrothal was announced on January 10, 1765.

King Christian VII by Nathaniel Dance-Holland, 1768; Credit – Wikipedia

On October 1, 1766, a proxy marriage was held at St. James’s Palace in London, with Caroline Matilda’s brother King George III standing in for King Christian VII. Fifteen-year-old Caroline Matilda soon left England for Denmark with a large contingent of attendants and servants. When she crossed the Danish border, Danish envoys sent her English attendants and servants back and replaced them with Danish ones. Caroline Matilda arrived in Copenhagen on November 8, 1766, and married Christian in person later that day in the Christiansborg Palace Chapel.

A copperplate engraving depicting the first dance of King Christian VII and Queen Caroline Mathilde at their wedding at Christiansborg Palace; Credit – Wikipedia

Caroline Matilda and Christian had two children, but it is probable that Christian was not the father of Louise Auguste.

- King Frederik VI of Denmark and Norway (1768 – 1839), married Princess Marie of Hesse-Kassel, had issue but the only surviving children were two daughters

- Princess Louise Auguste (1771 – 1843), married Friedrich Christian II, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg, had issue including Caroline Amalie, Queen Consort of King Christian VIII of Denmark

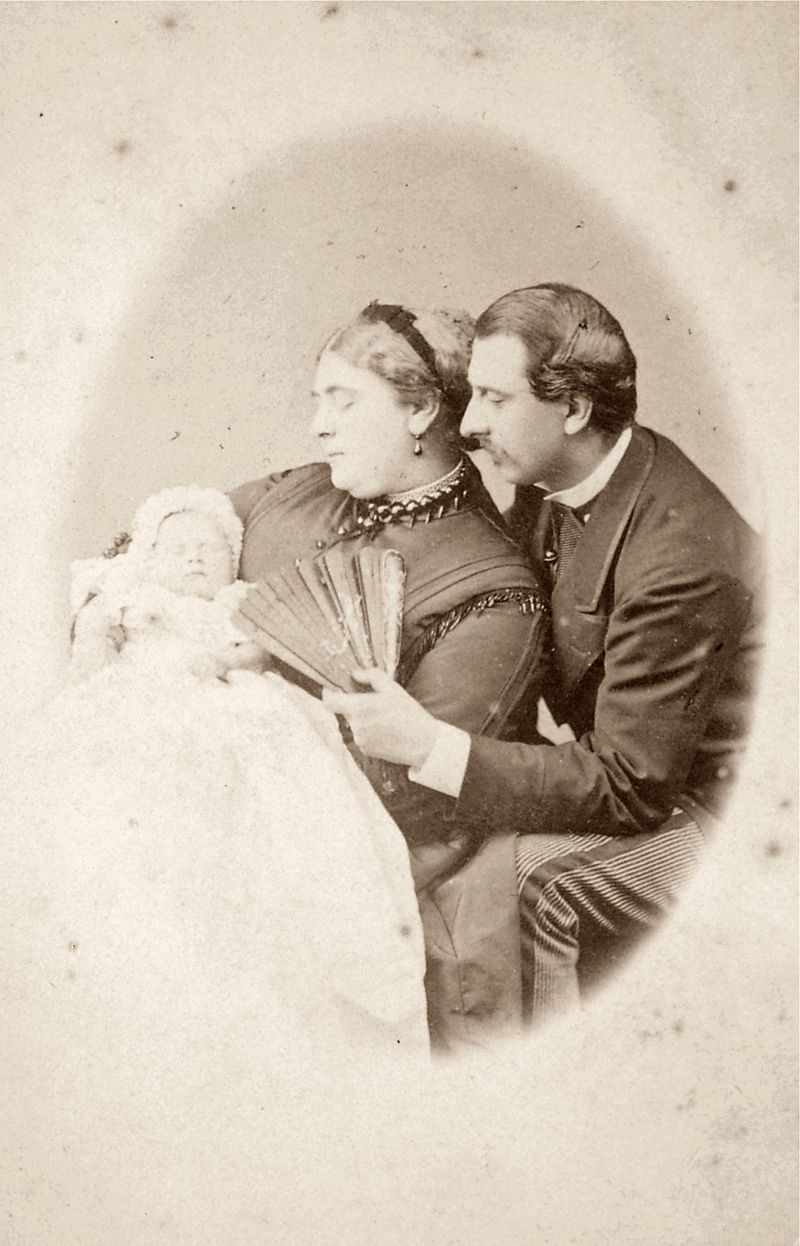

Engraving of the newborn Crown Prince Frederik with his mother Queen Caroline Matilda; Credit – Wikipedia

Princess Louise Auguste as a child. Pastel by H.P. Sturz, 1771; Credit – Wikipedia

Caroline Matilda soon became a victim of the intrigues of Queen Dowager Juliana Maria, the second wife of Christian’s father, who coveted the succession for her own son Frederik. Caroline Matilda also soon discovered that her husband was mentally ill. Christian was personable and intelligent as a child, but he was poorly educated and terrorized by a brutal governor, Christian Ditlev Reventlow, Count of Reventlow. It is unknown if Christian’s mental illness was caused by the brutal treatment of the Count of Reventlow, possible porphyria inherited from his Hanover mother, or schizophrenia. Christian’s behavior wandered into excesses, especially sexual promiscuity. He publicly declared that he could not love Caroline Matilda because it was “unfashionable to love one’s wife”. His symptoms included paranoia, self-mutilation, and hallucinations.

In May of 1768, Christian VII took a long tour of Europe, including stays in Altona (now in Germany, then in Denmark), Paris, and London. The trip had been arranged because it was believed that new environments could change Christian’s behavior. It was on this journey that he became acquainted with the physician Johann Friedrich Struensee. Struensee was the first person who understood that Christian was seriously ill. When Christian came home from the trip, Struensee accompanied him and was employed as Christian’s personal physician. Struensee could handle Christian’s instability, which was a great relief to the king’s advisers, and Christian developed confidence in him.

Johann Friedrich Struensee; Credit – Wikipedia

Because of Christian’s confidence in him, Struensee gained political power. In 1770, Struensee became Master of Requests and Minister of the Royal Cabinet. He also became the lover of the ill-treated Caroline Matilda, whose marriage was less than satisfactory. When Caroline Matilda gave birth to her daughter Louise Auguste, no one doubted that Struensee was the father of the princess, who was given the unflattering nickname la petite Struensee, although Christian VII officially acknowledged her as his daughter. Eventually, Queen Dowager Juliana Maria maneuvered a coup that would bring about the fall of Struensee and discredit Caroline Matilda.

Early on the morning of January 17, 1772, following a ball at the court theater at Christiansborg Palace, Christian was awakened and forced to sign orders for the arrest of Struensee, his friend Count Enevold Brandt, and Caroline Matilda. Caroline Matilda was immediately taken to Kronberg Castle in Helsingør, Denmark, immortalized as Elsinore in William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, to await her fate. She was allowed to keep her daughter with her, but the four-year-old Crown Prince Frederik stayed with his father. Upon hearing of Caroline Matilda’s arrest, Struensee confessed to his relationship with her, and eventually, Caroline Matilda also confessed. Struensee and Brandt were condemned to death and both suffered a brutal execution. In the presence of thousands of people, their right hands were severed first, then their bodies were broken on the wheel, and finally, they were beheaded.

Johann Friedrich Struensee and his companion Brandt are beheaded in Copenhagen on April 28, 1772; Credit – Wikipedia

Caroline Matilda and Christian’s marriage was dissolved on April 6, 1772. She lost her title of Queen and was forcibly separated from her children whom she never saw again. Caroline Matilda was not quite 20 years old. Originally, it was decided that Caroline Matilda was to be held in custody for life at Aalborghus Castle in Aalborg, Denmark, but her brother King George III intervened. King George III sent Sir Robert Murray Keith, a British diplomat, to negotiate her release from Danish imprisonment. On May 28, 1772, Caroline Matilda was sent to Celle in her brother’s Kingdom of Hanover and lived the rest of her life at Celle Castle.

Celle Castle; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Caroline Matilda’s dowry was restored and she was able to live in comfort, but she missed her children terribly. Her imprisonment was not to last long. Caroline Matilda died of “a putrid fever and sore throat,” probably scarlet fever, on May 10, 1775, at the age of 23 at Celle Castle in Celle, Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, now in Lower Saxony, Germany. She was buried at the Stadtkirche St. Marien in Celle next to his great-grandmother Sophie Dorothea of Celle who suffered a similar fate.

Stadtkirche St. Marien in Celle, Germany; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Caroline Matilda’s story was told in several novels including Norah Loft’s The Last Queen (1969) and Per Olov Enquist’s The Visit of the Royal Physician (1999) and also in the Danish film A Royal Affair (2012). Stella Tillyard also covers Caroline Matilda’s affair in her nonfiction book A Royal Affair: George III and His Scandalous Siblings (2006). King George III’s six daughters had very sheltered upbringings and they spent most of their time with their parents and each other. The living conditions of King George III’s daughters came to be known as “the Nunnery.” None of the daughters was allowed to marry at the age when most princesses would marry, and only three of the six daughters ever married. Perhaps this over-protection of King George III’s daughters was due to what happened to his sister Caroline Matilda when she married King Christian VII of Denmark.

The people of Celle raised money for a monument to Caroline Matilda which stands in the French Garden in Celle, now in Lower Saxony, Germany.

The Caroline Matilda Memorial in Celle; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Kingdom of Denmark Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Kingdom of Denmark Index

- Danish Orders and Honours

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Oldenburg, 1448 – 1863

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, 1863 – present

- Danish Royal Christenings

- Danish Royal Dates

- Danish Royal Residences

- Danish Royal Weddings

- Line of Succession to the Danish Throne

- Profiles of the Danish Royal Family

Works Cited

“Caroline Matilda of Great Britain.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 9 Sept. 2016. Web. 10 Sept. 2016.

“Christian VII of Denmark.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 31 Aug. 2016. Web. 10 Sept. 2016.

Hadlow, Janice. A Royal Experiment. New York: Picador, 2014. Print.

“Johann Friedrich Struensee.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 27 Aug. 2016. Web. 10 Sept. 2016.

Susan. “Sophia Dorothea of Celle, Electoral Princess of Hanover.” British Royals. Unofficial Royalty, 18 Dec. 2015. Web. 10 Sept. 2016.

Tillyard, Stella. A Royal Affair: George III and His Scandalous Siblings. New York: Random House, 2006. Print.

Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell, 1996. Print.