by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

Credit – Wikipedia

King William II Rufus of England was born in Normandy (now in France) between 1056 and 1060. He was the third of the four sons of King William I of England (the Conqueror) and Matilda of Flanders. At the time of William Rufus’ birth, his father was the Duke of Normandy.

William Rufus had at least nine siblings. The birth order of the boys is clear, but that of the girls is not. The list below is not in birth order. It lists William’s brothers first in their birth order and then his sisters in their probable birth order.

- Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy (1051-1054 – 1134), married Sybil of Conversano, had one son

- Richard of Normandy (circa 1054 – circa 1070), died in a hunting accident in the New Forest

- Henry I, King of England (1068 – 1135), married (1) Edith of Scotland, had one son and one daughter (2) Adeliza of Louvain, no children

- Agatha of Normandy died before 1074, unmarried

- Adeliza of Normandy (circa 1055 – before 1113), probably a nun at the Abbey of St Léger in Préaux, Duchy of Normandy

- Cecilia of Normandy (circa 1056 – 1127), Abbess of Holy Trinity in Caen

- Matilda of Normandy (circa 1061 – c. 1086)

- Constance of Normandy (1057-1061 – 1090, married Alan IV, Duke of Brittany, no issue

- Adela of Normandy (circa 1067 – 1137), married Stephen II, Count of Blois, had ten children including King Stephen of England

William Rufus had red hair and a ruddy complexion which earned him the nickname Rufus, by which he was known. He was educated with his brothers by Lanfranc, then the abbot of the Abbaye aux Hommes in Caen, later Archbishop of Canterbury. As the third son of the Duke of Normandy, William Rufus was destined to enter Holy Orders. However, the death of Richard, the second son, between 1069 and 1075, changed the situation. William Rufus was knighted and then served with his father in preparation for eventually being the heir to a portion of his father’s land. Chroniclers of the time described William Rufus as a good boy and respectful, loyal, and faithful to his father.

In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy invaded England and defeated the last Anglo-Saxon King, Harold II Godwinson, King of England at the Battle of Hastings. The Duke of Normandy was now also King William I of England. Even before the division of land occurred, William Rufus and his brothers had a strained relationship. The contemporary chronicler Orderic Vitalis, wrote about an incident that occurred at L’Aigle in Normandy in 1077. William Rufus and Henry grew bored with playing dice and decided to make mischief by emptying a chamber pot on their brother Robert from an upper gallery. Robert was infuriated, a brawl broke out and their father had to intercede to restore order. Angered because his father did not punish his brothers, Robert and his followers then attempted to siege the castle at Rouen (Normandy) but were forced to flee when the Duke of Normandy attacked their camp. This led to a three-year estrangement between Robert and his family which only ended through the efforts of Robert’s mother.

In 1087, King William I divided his lands between his two eldest surviving sons. Robert Curthose was to receive the Duchy of Normandy and William Rufus was to receive the Kingdom of England. Henry was to receive 5,000 pounds of silver and his mother’s English estates. King William I of England (the Conqueror) died on September 9, 1087. Robert Curthose became Robert II Curthouse, Duke of Normandy, and William Rufus became King William II Rufus of England. Henry received the money, but no land. William Rufus never married and had no children.

William Rufus and Robert Curthose continued having a strained relationship. William Rufus alternated between supporting Robert against the King of France and opposing him for the control of Normandy. Henry was constantly being forced to choose between his two brothers and whichever brother he picked, he was likely to annoy the other. After William I died and his lands were divided, nobles who had land in both Normandy and England found it impossible to serve two lords. If they supported William, then Robert might deprive them of their Norman land. If they supported Robert, then they were in danger of losing their English land.

The only solution the nobles saw was to reunite Normandy and England, and this led them to revolt against William in favor of Robert in the Rebellion of 1088, under the leadership of the Bishop Odo of Bayeux, the half-brother of William the Conqueror. The rebellion was unsuccessful partly because Robert never showed up to support the English rebels.

In 1096, Robert left for the Holy Land on the First Crusade. In order to raise money for the crusade, he mortgaged the Duchy of Normandy to his brother King William II Rufus. The two older brothers made a pact stating that if one of them died without heirs, both Normandy and England would be reunited under the surviving brother. William then ruled Normandy as regent in Robert’s absence. Robert did not return until September 1100, one month after William’s death.

Probably the most famous part of William Rufus’ life was his death. On August 2, 1100, King William II Rufus rode out from Winchester Castle on a hunting expedition to the New Forest, accompanied by his brother Henry and several nobles. His elder brother Richard, in circa 1070, and his nephew Richard, the illegitimate son of his brother Robert, in May 1100, had both been killed in hunting accidents in the New Forest.

According to most contemporary accounts, William Rufus was chasing after a stag followed by Walter Tirel, a noble. William Rufus shot an arrow but missed the stag. He then called out to Walter to shoot, which he did, but the arrow hit the king in his chest, puncturing his lungs, and killing him. Walter Tirel jumped on his horse and fled to France.

The next day, William Rufus’ body was found by a group of local farmers. The nobles had fled to their Norman and English lands to secure their possessions and ensure law and order following the death of the king. The farmers loaded the king’s body on a cart and brought it to Winchester Cathedral where he was buried under a plain flat marble stone below the tower with little ceremony.

William Rufus’ elder brother, Robert Curthose, was still on Crusade, so Henry was able to seize the crown of England for himself. Henry hurried to Winchester to secure the royal treasury. The day after William’s funeral at Winchester, the nobles elected Henry king. Henry then left for London where he was crowned three days after William’s death by Maurice, Bishop of London because there was no Archbishop of Canterbury at that time.

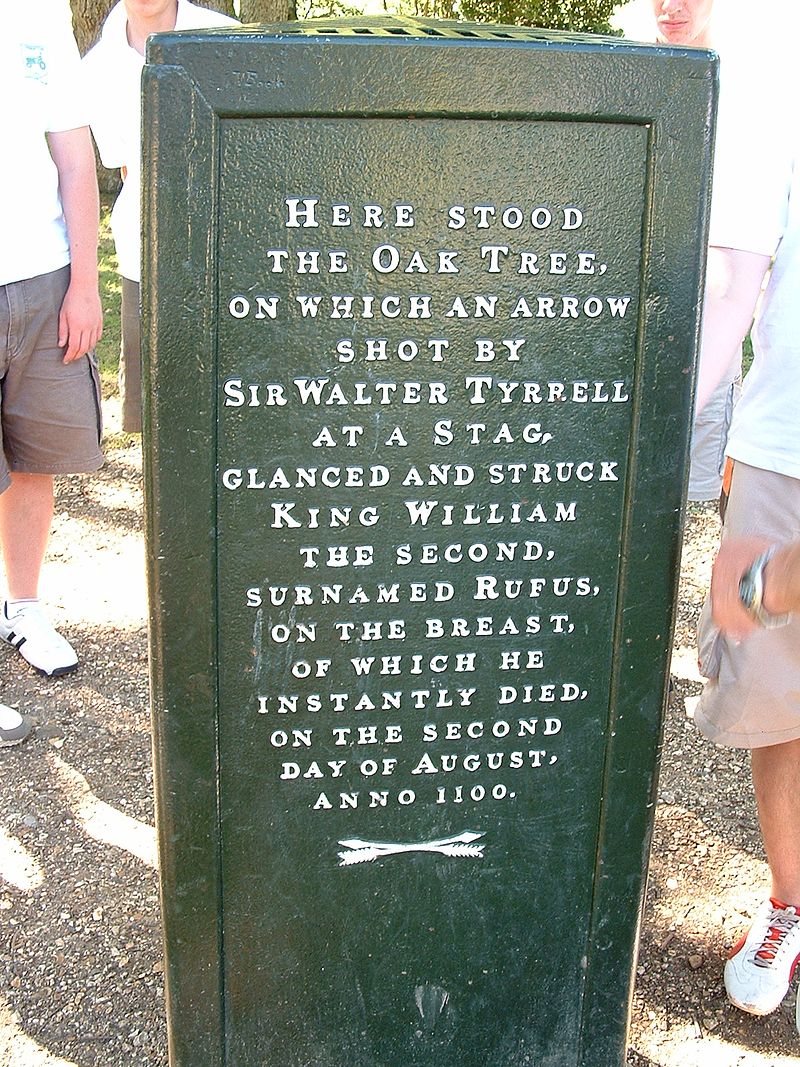

Was there a conspiracy to assassinate William Rufus? Walter Tirel was an excellent archer, but he badly missed his shot. William’s brother Henry was among the hunting party that day and would have benefited directly from William’s death. Some modern historians find the assassination theory credible. Others say that hunting accidents were common (William’s brother and nephew did die in hunting accidents) and there is not enough hard evidence to prove murder. In the New Forest, a memorial stone, known as the Rufus Stone, claims to marks the spot where William Rufus died.

Rufus Stone; Photo Credit – By Adem Djemil, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56115617

In 1107, the tower at Winchester Cathedral near William Rufus’ grave collapsed and the superstition at that time said that the presence of William Rufus’ remains was the cause. Around 1525, the royal remains in Winchester Cathedral were rearranged. William Rufus’ remains were transferred to one of the mortuary chests next to the mortuary chest of King Cnut the Great atop the stone wall around the high altar.

King Cnut the Great’s mortuary chest atop the wall; Photo Credit – http://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/

In 1642, Winchester Cathedral was sacked by Parliamentary Troops during the English Civil War. The remains in the mortuary chests were scattered around the cathedral. Later the remains were returned to the mortuary chests in no particular order. On February 3, 2015, this press release was published: “The Dean and Chapter of Winchester has announced that, as part of an initial assessment of the Cathedral’s Renaissance Mortuary Chests and an inventory of their contents, a project to record and analyze the contents has begun. The Chests are thought to contain the mortal remains of some of the early Royal Families of Wessex and of England, and three bishops, amongst other artifacts and mortal remains.” All the mortuary chests were brought to the Lady Chapel at Winchester Cathedral where a laboratory was set up. The chests are to be restored and conserved and modern technology will attempt to identify the remains. In 2012, an examination of the remains in the chests began and the project is still ongoing. The examination included DNA testing, reassembly of the skeletons, and analysis to determine the sex, age, and other characteristics of the remains. The six mortuary chests were found to hold the remains of at least 23 individuals, more than the 12 – 15 remains originally thought.

Mortuary Chests in the Lady Chapel at Winchester Cathedral; Photo Credit – http://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

England: House of Normandy Resources at Unofficial Royalty