by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

King Henry II of England; Credit – Wikipedia

King Henry II of England was born on March 5, 1133, in Le Mans, the capital of the County of Maine, now in France. He was the eldest of the three sons of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine, and Empress Matilda (sometimes called Maud or Maude). Henry’s mother was the widow of Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor and she used her style and title from her first marriage for the rest of her life. More importantly, Matilda was the only surviving, legitimate child of King Henry I of England and Duke of Normandy.

Empress Matilda; Credit – Wikipedia

Geoffrey V of Anjou; Credit – Wikipedia

On November 25, 1120, William Ætheling, Henry I’s only legitimate son, was returning to England from Normandy when his ship hit a submerged rock, capsized, and sank. William Ætheling and many others drowned. See Unofficial Royalty: The Sinking of the White Ship and How It Affected the English Succession. King Henry I holds the record for the British monarch with the most illegitimate children, 25 or so illegitimate children, but the tragedy of the White Ship left him with only one legitimate child, his daughter Matilda. Henry I’s nephews were the closest male heirs. In January of 1121, Henry I married Adeliza of Louvain, hoping for sons, but the marriage remained childless. On Christmas Day of 1226, King Henry I of England gathered his nobles at Westminster where they swore to recognize Matilda and any future legitimate heir she might have as his successors. That plan did not work out.

Henry I died on December 1, 1135. He had fallen ill after eating a number of lampreys against his doctor’s advice. It is possible the cause of death was ptomaine poisoning. Upon hearing of Henry I’s death, Stephen of Blois, one of Henry I’s nephews, quickly crossed the English Channel from France, seized power, and was crowned King of England on December 22, 1135. This started the terrible civil war between Stephen and Matilda known as The Anarchy. Henry II was two years old when this civil war started and it was to affect his childhood as England did not see peace for 18 years.

Henry had two younger brothers, but both died in their 20s and were unmarried.

- Geoffrey, Count of Nantes (1134 – 1158), unmarried

- William, Viscount of Dieppe (1136–1164), unmarried

Henry’s father, Geoffrey of Anjou, had a few illegitimate children. One of them, Hamelin, was a prominent person at Henry’s court and the courts of Henry’s sons King Richard I and King John. Henry arranged for Hamelin to marry one of the wealthiest heiresses in England, Isabel de Warenne, 4th Countess of Surrey and Hamelin took the style of her name and title, Hamelin de Warenne, Earl of Surrey. Hamelin and Isabel had one son and four daughters.

During much of Henry’s early life, his mother was away in England fighting her cousin Stephen for the crown of England. Geoffrey of Anjou took no direct part in the conflict in England, leaving it to his wife Matilda, the oldest illegitimate son of her father Henry I, Robert Fitzroy, 1st Earl of Gloucester and her uncle King David I of Scotland. Instead, Geoffrey took advantage of the confusion the conflict caused and attacked the Duchy of Normandy. By 1144, he had taken control of all of Normandy and assumed the title Duke of Normandy. Geoffrey held the duchy until 1150 when he and Matilda together ceded the Duchy of Normandy to their son Henry.

Henry’s received his early education in Anjou from Peter of Saintes, a well-known classical scholar. In 1142, Geoffrey decided to send nine-year-old Henry to Bristol, England, which was the center of the Angevin opposition to Stephen. While in England, Henry lived in the household of his uncle Robert of Gloucester and was tutored along with Roger of Worcester, one of Robert’s sons. The canons of St Augustine’s in Bristol also helped in Henry’s education. Henry returned to Anjou in either 1143 or 1144, resuming his education under William of Conches, another famous academic. Henry spoke French and Latin and understood Provençal, Italian, and English. The young Henry made two unsuccessful military expeditions to England in 1147 and 1149.

Geoffrey died in September 1151, and Henry was now Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, and Count of Nantes. He postponed his plans to return to England, as he first needed to ensure that his succession in both Normandy and his father’s lands was secure. At around this time, Henry was also probably secretly planning his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, then still the wife of King Louis VII of France. Eleanor, eleven years older than Henry, was the Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right, and marriage to her would greatly increase Henry’s lands. Eleanor had failed to give Louis any sons and Louis had the marriage annulled. 19-year-old Henry married 30-year-old Eleanor eight weeks later, on May 18, 1152, in Bordeaux in Eleanor’s Duchy of Aquitaine.

Henry and Eleanor had eight children and were the grandparents of many sovereigns and queen consorts.

- William IX, Count of Poitiers (1153 – 1156), died in childhood

- Henry the Young King (1155 – 1183), married Marguerite of France, no children

- Matilda of England, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria (1156 – 1189), married Heinrich the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, had five children, including Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor

- King Richard I of England (1157 – 1199), married Berengaria of Navarre, no children

- Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany (1158 – 1186), married Constance, Duchess of Brittany, had three children

- Eleanor of England, Queen of Castile (1162 – 1214), married King Alfonso VIII of Castile, had twelve children including King Enrique I of Castile; Berengaria, Queen Regnant of Castile and Queen of León; Urraca, Queen of Portugal; Blanche, Queen of France, and Eleanor, Queen of Aragon

- Joan of England, Queen of Sicily (1165 – 1199), married (1) King William II of Sicily, no surviving children (2) Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, had two children, Joan died in childbirth with her third child who also died

- King John of England (1166 – 1216), married 1) Isabella, 3rd Countess of Gloucester, marriage annulled, no children (2) Isabella, Countess of Angoulême; had five children, including King Henry III of England; Joan of England, Queen of Scots, and Isabella of England, Holy Roman Empress

13th-century depiction of Henry and his legitimate children: (l to r) William, Young Henry, Richard, Matilda, Geoffrey, Eleanor, Joan, and John; Credit – Wikipedia

Henry acknowledged two illegitimate sons::

- Geoffrey, Archbishop of York (c. 1152 – 1212), sometimes called Geoffrey Plantagenet, FitzPlantagenet, or FitzRoy, mother uncertain, she may have been named Ykenai and there is speculation that she could have been a prostitute, the daughter of a knight, a Welsh hostage, a servant, or a daughter of one of the royal servants

- William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury (c. 1176 – 1226), his mother was probably Ida de Tosny, married Ela of Salisbury, 3rd Countess of Salisbury, had issue

The civil war between first cousins Empress Matilda and Stephen of Blois, King of England since 1135 had dragged on for many years. Contemporary chroniclers described the period “when Christ and his saints slept” and Victorian historians called the conflict “the Anarchy” because of the chaos, although modern historians have questioned the accuracy of the term and some contemporary accounts. Despite this modern hindsight, the 18-year civil war must have been a difficult period for many.

Stephen unsuccessfully attempted to have his son Eustace, recognized by the Church as the next King of England. By the early 1150s, most of the barons and the Church wanted long-term peace. Ironically, Stephen’s son Eustace died on the same day that Henry’s eldest son William was born. Although William died when he was three years old, the irony of the birth and the death must have been noticed at the time.

When Henry re-invaded England in 1153, neither side’s forces were eager to fight. After limited campaigning and the siege of Wallingford, Stephen and Henry agreed upon a negotiated peace, the Treaty of Winchester, in which Stephen recognized Henry as his heir. Stephen died on October 25, 1154, and Henry ascended the throne as King Henry II, the first Angevin King of England. Henry was crowned at Westminster Abbey In London, England on December 19, 1154. Eleanor was not crowned with Henry. At that time, she was late in her pregnancy with her second son Henry the Young King, who was born on February 28, 1155. Eleanor also had children in 1156, 1157, and 1158 and her coronation was eventually held at Worcester Cathedral on December 25, 1158.

12th-century depiction of Henry and Eleanor holding court; Credit – Wikipedia

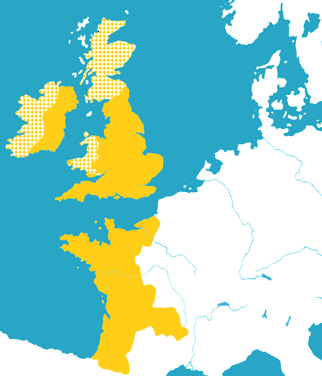

The early years of Henry’s reign were spent restoring law and order and recovering the Crown land that King Stephen had bestowed on his supporters. Henry was assisted by the Church and Thomas Becket, a clerk in the household of Theobold of Bec, Archbishop of Canterbury. Becket’s indispensability caused Henry to appoint Becket as Lord Chancellor in January of 1155. During the reign of Henry, the lands of the Angevin Empire were vast and consisted of an area covering half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and Wales.

Angevin Empire around 1172, solid yellow shows Angevin possessions, checked yellow shows areas where there was Angevin influence; By Cartedaos (talk) 01:46, 14 September 2008 (UTC) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4781085

Henry’s plans to invade Ireland in 1155 fell through, but Malcolm IV, King of Scots was forced to restore to England the land that had been ceded to his grandfather David I, King of Scots. An invasion of Wales occurred in 1157 and then two years later, there was an unsuccessful campaign in France to assert Eleanor’s claim to the County of Toulouse. Henry concluded an uneasy peace with Eleanor’s first husband King Louis VII of France. In 1160, Louis’ two-year-old daughter Marguerite by his second wife was married to Henry and Eleanor’s five-year-old eldest surviving son Henry. The reason for the early marriage was political. Marguerite’s dowry included the disputed territory of the Vexin and King Henry II wanted to possess it.

After taking care of his issues in France, Henry returned to England in 1163 and immediately began a conflict with the Church that would occupy the next several years of his reign. In 1162, Henry named his Chancellor Thomas Becket the Archbishop of Canterbury following the death of the previous Archbishop, Theobold of Bec. Henry hoped that by appointing Becket the royal supremacy over the English Church would return to what it had been in the days of Henry’s grandfather, King Henry I. However, Becket wanted to prove that he was no mouthpiece for Henry. An argument developed between the two men over the issue of whether clergy who had committed secular crimes should be tried in secular courts or church courts. Even those men who took minor orders were considered clergy, the quarrel potentially covered up to 20% of the male population of England at the time.

Early 14th-century representation of Henry and Thomas Becket; Credit – Wikipedia

On June 14, 1170, Henry II’s eldest surviving son, Henry the Young King, was crowned junior King of England while Henry II was still alive, adopting the practice of the French monarchy. Roger de Pont L’Évêque, Archbishop of York, Gilbert Foliot, Bishop of London, and Josceline de Bohon, Bishop of Salisbury all participated in the crowning. This infringed on the right of Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury to crown English monarchs and drove Pope Alexander III to allow Becket to lay an interdict on England as punishment, which would forbid the public celebration of sacred rites. This threat forced Henry back to negotiations and terms were agreed to finally in July 1170.

Becket returned to England in early December 1170. Just when the dispute with Henry II seemed resolved, Becket excommunicated the three bishops who had participated in the crowning of Henry the Young King. Henry’s anger at the timing of the excommunications led him to supposedly ask the question: “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” This inspired four knights to set off from Henry’s court in Normandy to Canterbury, where on December 29, 1170, they murdered Becket while he was at prayers in Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, England. Henry performed a public act of penance on July 12, 1174, at Canterbury Cathedral, when he publicly confessed his sins, then allowed each bishop present to give him five hits with a rod, and then each of the 80 monks of Canterbury Cathedral gave him three hits with a rod. Finally, Henry offered gifts to Becket’s shrine and spent a vigil at Becket’s tomb.

The last part of Henry’s reign was taken up by disputes with and between his sons, often encouraged by Eleanor. As Henry’s children grew up, tensions over the future inheritance of the empire began to emerge, encouraged by King Louis VII of France and then his son King Philip II of France. In 1173, Henry the Young King rebelled in protest and was joined by his brothers Richard and Geoffrey, and by their mother Eleanor. France, Scotland, Flanders, and Boulogne allied themselves with the rebels. Henry eventually defeated the revolt and had Eleanor imprisoned for the next sixteen years for her part in inciting their sons. In 1182–83, Henry the Young King had a falling out with his brother Richard when Richard refused to pay homage to him on the orders of King Henry II. As he was preparing to fight Richard, Henry the Young King became ill with dysentery (also called the bloody flux), the scourge of armies for centuries, and died. In 1186, Henry II’s third son Geoffrey was trampled to death during a jousting tournament in Paris.

By the time Henry turned age 56 in 1189, he was prematurely aged. Two sons were left: Richard, the second son, Eleanor’s favorite and the heir since his elder brother’s death, and John, the youngest child and Henry’s favorite. King Philip II of France successfully played upon Richard’s fears that Henry would make John King, and a final rebellion broke out in 1189. Decisively defeated by Philip and Richard and suffering from a bleeding ulcer, Henry retreated to his favorite residence, the Château de Chinon in Anjou. There he was told that John had publicly sided with Richard in the rebellion, and this broke his heart. Only his illegitimate son Geoffrey, was at his father’s deathbed and it moved Henry to observe that his illegitimate son had proved more loyal than his legitimate sons: “Baseborn indeed have my other children shown themselves. This alone is my true son.” King Henry II of England died at the Château de Chinon on July 6, 1189, at the age of 56, and was succeeded by his son Richard. Henry was buried at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou, France. The abbey church was pillaged and looted by the Huguenots in 1562. There are stories that the royal remains were thrown into a nearby river and also that the monks reburied them in a secret location. However, the beautiful effigies were not damaged and can still be seen today.

Effigies of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Using today’s technology, there is a video that does a facial reconstruction using Henry’s effigy.

YouTube: The Face of Henry II (Photoshop Reconstruction)

In popular culture, Henry II and his family are the subjects of plays, films, and historical fiction. There have been two plays specifically about the Thomas Becket controversy, T.S. Eliot‘s 1935 play Murder in the Cathedral and Jean Anouilh‘s 1959 play Becket. Becket was adapted as a film in 1964 with Peter O’Toole as Henry and Richard Burton as Thomas Becket. Henry, Eleanor, and their sons Richard, Geoffrey, and John are characters in James Goldman‘s 1966 play The Lion in Winter and in the 1968 film adaption of the play with Peter O’Toole once again playing Henry and Katharine Hepburn in an Academy Award-winning role as Eleanor.

The late historical fiction author Sharon Kay Penman‘s excellently researched and highly recommended Plantagenet Series deals Henry II and his family.

- When Christ and His Saints Slept (1995) introduces the beginnings of the Plantagenet dynasty as Empress Matilda (Penman uses Maude) fights to secure her claim to the English throne.

- Time and Chance (2002) continues the story of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine and focuses on the rift between Henry II and Thomas Becket.

- Devil’s Brood (2008) opens with the conflict between Henry II, his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, and their four sons, which escalates into a decade of warfare and rebellion pitting the sons against the father and the brothers against each other while Eleanor spends the period imprisoned by Henry.

- Lionheart (2011) focuses on Richard the Lionheart’s Crusades in the Holy Land and on what happened to Eleanor when she was finally released after spending sixteen years in confinement that was ordered and enforced by her husband.

- A King’s Ransom (2014) is about the second half of Richard’s life, during and following his imprisonment, ransom, and life afterward.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

England: House of Angevin Resources at Unofficial Royalty