by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

Berlin Cathedral; Credit – By Ansgar Koreng / CC BY 3.0 (DE), CC BY 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41469664

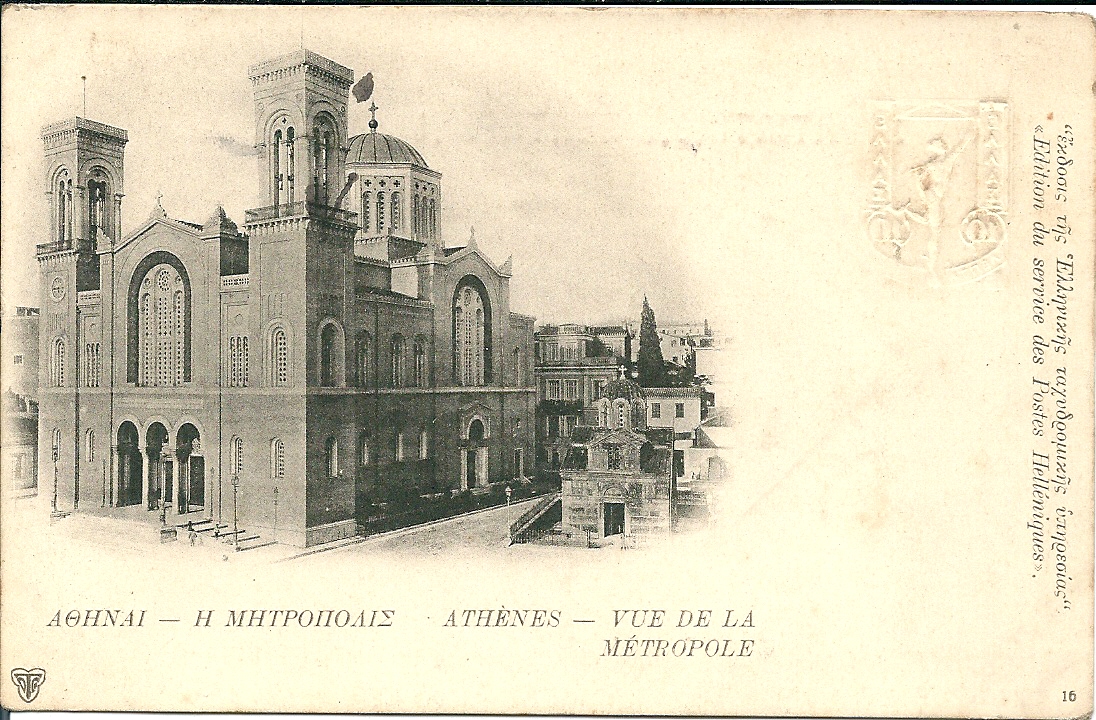

Located in Berlin, the capital of Germany, the Berlin Cathedral, known in German as the Berliner Dom, is a member of the Evangelical Church in Germany, a federation of twenty Lutheran, Reformed (Calvinist), and United (Prussian Union, for example) Protestant regional churches and denominations in Germany. As with many churches in Europe, the religious affiliation of the Berlin Cathedral has changed over the centuries: Roman Catholic until 1539, Lutheran from 1539–1632, Reformed from 1632–1817, and United (Prussian Union) from 1817 – present. The current church was built from 1894 to 1905 during the reign of Wilhelm II, the last German Emperor and King of Prussia. Although lesser well known than other royal burial sites, the Hohenzollern Crypt in the Berlin Cathedral is the most important dynastic burial site in Germany and rivals the Imperial Crypt at the Capuchin Church in Vienna, Austria, Westminster Abbey in London, England, the Basilica of Saint-Denis near Paris, France, and the Royal Basilica of San Lorenzo de El Escorial in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain.

*********************

House of Hohenzollern

Wilhelm II, the last German Emperor and King of Prussia; Credit – Wikipedia

The Protestant Franconian branch of the House of Hohenzollern ruled as Margraves of Brandenburg, Dukes of Prussia, Electors of Brandenburg, Kings of Prussia from 1415 until 1918. The first King in Prussia succeeded his father as Friedrich III, Duke of Prussia, Elector of Brandenburg in 1688. The Electorate of Brandenburg was part of the Holy Roman Empire, while the Duchy of Prussia, formerly a fief of the Crown of Poland, lay outside the Empire’s borders. The Duchy had been inherited by the Hohenzollern Prince-Electors of Brandenburg in 1618 and was ruled in personal union.

Friedrich I, the first King in Prussia, formerly Friedrich III, Duke of Prussia, Elector of Brandenburg; Credit – Wikipedia

In November 1700, in exchange for supporting the Holy Roman Empire in the Spanish War of Succession, Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor agreed to allow Friedrich III, Duke of Prussia, Elector of Brandenburg to make Prussia a kingdom and become its first king. Because the Hohenzollerns’ sovereignty over the Duchy of Prussia was dependant upon succession in the male line (and would return to the Polish crown if there were no male heirs to succeed), Friedrich I agreed to style himself King in Prussia and not King of Prussia. In 1772, King Friedrich II (the Great) in Prussia, through several battles and wars, united the various parts of his kingdom, taking the title King of Prussia.

In 1871, the German Empire, consisting of four kingdoms, six grand duchies, five duchies, seven principalities, three free Hanseatic cities, and one imperial territory, was proclaimed. The King of Prussia was also the German Emperor (Kaiser). In the aftermath of World War I, Prussia had a revolution that resulted in the replacement of the monarchy with a republic. Wilhelm II, German Emperor, King of Prussia abdicated on November 9, 1918. On November 10, 1918, Wilhelm Hohenzollern crossed the border by train and went into exile in the Netherlands, never to return to Germany.

The Kingdom of Prussia had territory that today is part of Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia, and Switzerland. All or parts of the following states of today’s Germany were part of the Kingdom of Prussia: Brandenburg, Hesse, Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia, Saarland, Saxony-Anhalt, and Schleswig-Holstein.

*********************

History of the Berlin Cathedral

The Berlin Cathedral; Credit – By Thomas Wolf, www.foto-tw.de, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64059550

The original church was consecrated in 1454, as the Roman Catholic St. Erasmus Chapel, the chapel of the Berlin Palace, the main residence of the House of Hohenzollern from 1443 – 1918. St. Erasmus Chapel was used for the services of the family of the Elector of Brandenburg and the court. In 1465, Pope Paul II raised it to the status of a collegiate church. Eventually, the chapel could not meet the growing needs of the Electors of Brandenburg.

The first cathedral, used 1536–1747; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1535, the Dominican monastery church south of the Berlin Palace was converted into the first cathedral. The Gothic brick church was expanded and richly furnished. A burial site for the House of Hohenzollern was established. The new cathedral was consecrated in 1536. A new western façade with two towers was built in 1538. Joachim II Hector, Elector of Brandenburg converted to Lutheranism in 1539 and the Catholic cathedral became a Protestant cathedral.

Model of the Baroque cathedral by Jan Boumann and Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff; Credit – Wikipedia

Over the years, the Gothic brick cathedral became dilapidated. From 1747 – 1750, Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia had a new Baroque cathedral, designed by Dutch architect Jan Boumann and Prussian architect and painter Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, built where the current cathedral stands today. After the coffins of the Hohenzollern family members were transferred to the new cathedral, the old cathedral was demolished to clear space for the Baroque extension of the Berlin Palace. On September 6, 1750, the new Baroque cathedral was consecrated. Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel remodeled the interior in 1817 and the exterior in 1820 – 1822 in the Neoclassicist style.

Model of Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s remodeling of the exterior in the Neoclassicist style; Credit – Wikipedia

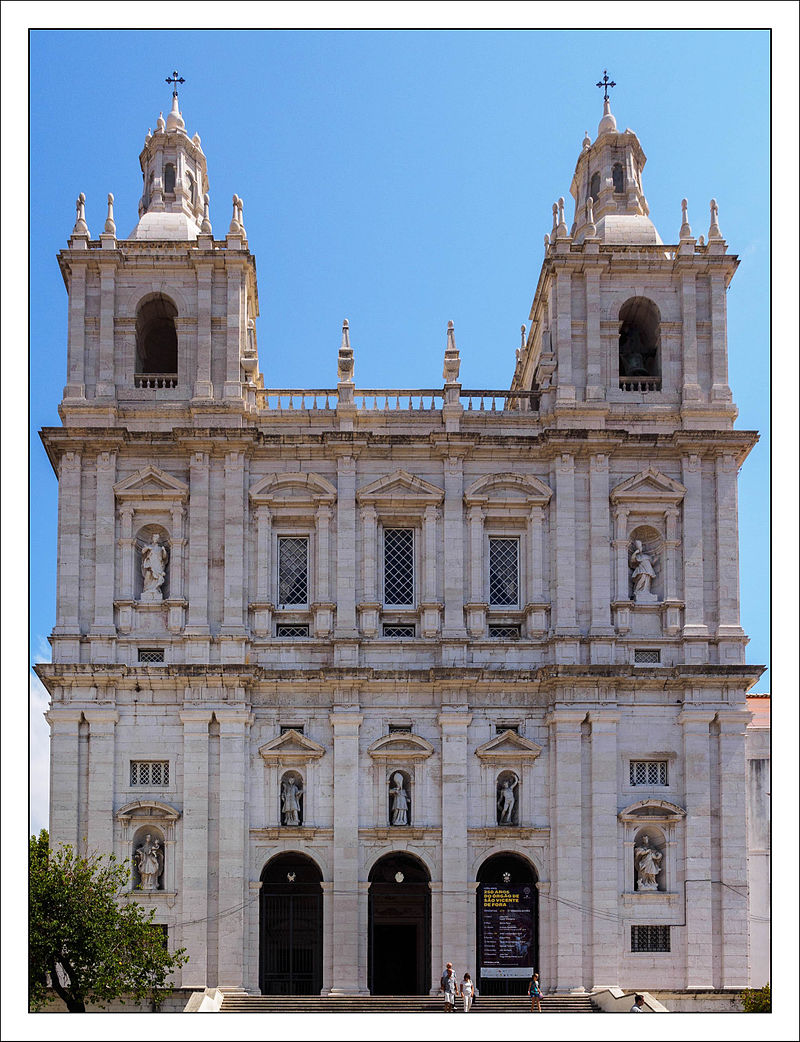

After the founding of the German Empire in 1871, there had been calls for a new church that could compete with the major churches in the world and impressively replace the previous churches. In 1885, Prussian architect Julius Carl Raschdorff, professor of architecture at the Technical University of Berlin, presented plans for a new cathedral in an adaptation of the Italian High Renaissance style and influenced by the Baroque style. After dismantling the movable interior decorations (altar, paintings, tombs), the cathedral designed by Boumann and von Knobelsdorff was demolished in 1893. The cornerstone for the new cathedral was laid on June 17, 1894, with the goal of consecrating the cathedral in 1900. However, due to construction delays, the consecration did not take place until February 27, 1905. The state paid the entire construction cost. The new cathedral was much larger than any of the previous churches and was considered a Protestant rival to the Roman Catholic St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

Berlin Cathedral in 1905; Credit – Wikipedia

*********************

World War II Destruction and Reconstruction

Berlin Cathedral in May 1945 with much damage, compare it to the photo above; Credit – Wikipedia

The Berlin Cathedral suffered much damage during World War II. Allied air raids destroyed windows and major cracks appeared on the cupolas of the corner towers. On May 24, 1944, the dome and its cupola lantern were hit by a bomb of combustible liquids. The resulting fire was unreachable and could not be extinguished. The entire cupola lantern fell into the interior of the cathedral, smashing through the floor with its enormous weight and damaging large parts of the Hohenzollern Crypt and some of its coffins below. By the end of World War II, twenty-five percent of the Berlin Cathedral had been destroyed.

The damaged sarcophagus of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia; Credit – Von Colin Pelka – Selbst fotografiert, Gemeinfrei, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23256455

After World War II, when Berlin and Germany were divided, the Berlin Cathedral was located in East Berlin in the Communist German Democratic Republic also known as East Germany. The East German government promoted state atheism although some people remained loyal to Christian churches. To protect the interior of the cathedral while the status of the Berlin Cathedral was debated, a temporary roof was built between 1949 – 1953. The Berlin Palace, which had also been damaged, was demolished by the East German government in 1950. Serious consideration was given to also demolishing the Berlin Cathedral. Following lengthy and extensive negotiations, an agreement was finally reached between the government of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), the Federation of Protestant Churches in the GDR, and the churches in the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), which provided for the reconstruction.

Memorial Church section of the Berlin Cathedral with the Hohenzollern Crypt access in 1900; Credit – Wikipedia

However, the Communist East German government had two demands. First, it demanded the removal of as many crosses as possible. The second demand dealt with the Memorial Church (Denkmalskirch) section on the north side of the Berlin Cathedral that contained the ceremonial sarcophagi (cenotaphs or empty tombs) of Johann Cicero, Elector of Brandenburg, Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg and his wife Dorothea Sophie of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, Friedrich I, King in Prussia and his wife Sophie Charlotte of Hanover, and Friedrich III, German Emperor and King of Prussia. In the middle of the Memorial Church was the access to the Hohenzollern Crypt. Although the Memorial Church section of the Berlin Cathedral had survived World War II intact, it was demolished by the Communist East German government in 1975 for ideological reasons due to it being a place of honor for the Hohenzollern dynasty. The ceremonial sarcophagi were moved into the Sermon Church (Predigtkirche), the main part of the cathedral.

Rüdiger Hoth, a German civil engineer, was hired as the master builder in 1975. During many meetings with the East German government, Hoth successfully negotiated that the cathedral would be largely reconstructed according to the 1885 designs of Julius Raschdorff.

In 1980, the Baptismal and Matrimonial Church (Tauf- und Traukirche) on the south side of the cathedral was reopened for services. The restoration of the large main part, the Sermon Church (Predigtkirche), in the center, began in 1984. Berlin Cathedral was finally able to be re-consecrated during a celebratory service on June 6, 1993, with the participation of numerous prominent guests in what was now a unified Germany, reunified since October 3, 1990.

*********************

Interior of the Berlin Cathedral

Interior of the Berlin Cathedral; Credit- By Steve Collis from Melbourne, Australia – Berliner Dom (HDR), CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24306403

In the center of the large dome is a round window showing the Holy Spirit as a dove in a halo. Around the round window are eight large mosaics depicting the Beatitudes of the Sermon on the Mount created by Prussian painter Anton von Werner.

The dome of the Berlin Cathedral; Credit – Von Svein-Magne Tunli – tunliweb.no – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56131113

The main altar comes from the previous cathedral and was the work of Prussian architect Friedrich August Stüler, and consists of a marble table supported by Corinthian columns with a crucifix, and a gilded wooden stand with the statues of the twelve apostles. On both sides of the altar are two large Baroque candelabras. The three paintings above the altar by Anton von Werner depict scenes from the life of Jesus: the Nativity, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection.

The main altar: Credit – By Mathew Schwartz – Imported from 500px (archived version) by the Archive Team. (detail page), CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75775034

*********************

The Hohenzollern Crypt

The Hohenzollern Crypt: Credit – By Rolf Dietrich Brecher from Germany – Hohenzollerngruft I, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63622648

The Hohenzollern Crypt, which occupies almost the entire basement of the Berlin Cathedral, is the most important dynastic burial site in Germany. A total of 94 members of the House of Hohenzollern have been interred there from 1595 – 1873. The sarcophagi and coffins, some simple and some quite elaborate, represent all artistic styles from late Gothic onwards and were made from stone, metal, or textile-covered wood.

Styles of coffins; Credit – By Steve Collis from Melbourne, Australia – Berliner Dom Crypt, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24306375

With the expansion of Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam near Berlin, the Hohenzollern Crypt fell out of favor as a burial site. Some of the Prussian royals were buried in the Friedenskirche (Church of Peace) as well as elsewhere on the grounds of Sanssouci Palace. Several chose to be buried in a mausoleum at Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin. The last German Emperor, Wilhelm II, was entombed in a mausoleum built on the grounds of Huis Doorn, his home in exile in the Netherlands, while his two wives were buried at the Antique Temple on the grounds of Sanssouci Palace.

Credit – By Rolf Dietrich Brecher from Germany – A lot of coffins – Generations.., CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63652230

During the reconstruction of the Berlin Cathedral overseen by civil engineer Rüdiger Hoth, who served as the master builder on the project, the Hohenzollern Crypt was refurbished. Hoth said of the crypt, “It was always considered a private family crypt in the time of the kaisers, and commoners were not allowed to come in but today we think it is historically and culturally important to Germans to be in touch with this part of their past.” Refurbished with white marble floors, whitewashed walls, and soft lighting, the Hohenzollern Crypt was opened to the public for the first time ever on November 20, 1999.

A child’s coffin; Credit – By Pudelek (Marcin Szala) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17789259

There had been discussion concerning whether Hohenzollerns buried elsewhere should be moved to the refurbished Hohenzollern Crypt. However, historians and descendants of the Hohenzollerns rejected the idea of moving the remains of Hohenzollerns whose express wishes were to be buried elsewhere. Prince Wilhelm-Karl of Prussia (born 1955), a great-grandson of Wilhelm II, the last German Emperor and King of Prussia said, “I believe the wishes of the deceased should be respected.” He did find the public gawking at his family’s burial crypt “a little unsettling.” However, he agreed with the head of the Prussian branch of the House of Hohenzollern Prince Georg Friedrich of Prussia (born 1976), the great-great-grandson and heir of Wilhelm II, that the burial site belongs to German history and, therefore, to the general public.

Credit – By Jorge Láscar from Australia – Crypt and intricate sarcophagi – Berliner Dom, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31952300

Those buried in the Hohenzollern Crypt at the Berlin Cathedral:

- Elisabeth Magdalene of Brandenburg, Duchess of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1537 – 1595), daughter of Joachim II, Elector of Brandenburg and wife of Franz Otto, Duke of of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Johann Georg, Elector of Brandenburg (1525 – 1598)

- Albrecht Friedrich of Brandenburg (1582 – 1600), son Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Joachim of Brandenburg (1583 – 1600), son of Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Augustus of Brandenburg (1580 – 1601), son of Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Catherine of Brandenburg-Küstrin, Electress of Brandenbueg (1549 – 1602), first wife of Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Elisabeth of Anhalt-Zerbst, Electress of Brandenburg (1563 – 1607), wife of Elector Johann Georg, Elector of Brandenburg

- Eleonore of Prussia, Electress of Brandenburg (1583–1607), second wife Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg (1546 – 1608)

- Albrecht Christian of Brandenburg (born and died 1609), son of Johann Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg

- Ernst of Brandenburg (1583 – 1613), son of Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Georg of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf (1613 – 1614), son of Johann Georg of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf, grandson of Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Johann Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg (1572 – 1620)

- Albrecht of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf (1614 – 1620), son of Johann Georg of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf, grandson of Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Catharina Sibylla of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf (born and died 1615), daughter of of Johann Georg of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf, granddaughter of Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg (born and died 1624), son of Georg Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Joachim Sigismund of Brandenburg (1603 -1625), son of Johann Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg

- Ernst of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf (1617–1642), son of Johann Georg of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf, grandson of Joachim Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg

- Wilhelm Heinrich of Brandenburg (1648 – 1649), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Anna Sophia of Brandenburg (1598 – 1659), daughter of Johann Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, wife of Friedrich Ulrich, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate, Electress of Brandenburg (1597 – 1660), wife of Georg Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Heinrich of Brandenburg (born and died 1664), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Amalia of Brandenburg (1664 – 1665), daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Katharina Sofie of the Palatinate (1594 – 1665), daughter of Friedrich IV, Elector Palatine, sister of Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate, Electress of Brandenburg

- Luise Henriette of Nassau, Electress of Brandenburg (1627–1667), first wife of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Karl Emil, Electoral Prince of Brandenburg (1655 – 1674), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Dorothea of Brandenburg (1675 – 1676), daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Elisabeth Henriette of Hesse-Kassel, Electoral Princess of Brandenburg (1661 – 1683), first wife of the future Friedrich I, King in Prussia

- Friedrich August of Brandenbrg (1685 – 1686), son of the future Friedrich I, King in Prussia

- Ludwig of Brandenburg (1666 – 1687), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg (1620 – 1688)

- Dorothea Sophie of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, Electress of Brandenburg (1636 – 1689), second wife of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Karl Philipp of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1673 – 1695), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Friederike of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1700 – 1701), daughter of Philipp Wilhelm, Margarve of Brandenburg-Schwedt

- Georg Wilhelm von Brandenburg-Schwedt (born and died 1704), son of Philipp Wilhelm, Margarve of Brandenburg-Schwedt

- Sophie Charlotte of Hanover, Queen in Prussia (1668 – 1705), second wife of Friedrich I, King in Prussia

- Friedrich of of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1704 – 1707), son of Albrecht Friedrich of Brandenburg-Schwedt, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Friedrich Ludwig of Prussia (1707 – 1708), son of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia (1710 – 1711), son of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Philipp Wilhelm, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1669 – 1711), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Friedrich I, King in Prussia (1657 – 1713)

- Charlotte Albertine of Prussia (1713 – 1714), daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Ludwig of Prussia (1717 – 1719), son of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Luise Wilhelmine of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1709 – 1726), daughter of Albrecht Friedrich of Brandenburg-Schwedt, granddaughter of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Albrecht Friedrich of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1672 – 1731), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1677 – 1734), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Friedrich of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1710 – 1741), son of Albrecht Friedrich of Brandenburg-Schwedt, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1715 – 1744), son of Albrecht Friedrich of Brandenburg-Schwedt, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Sophie Dorothea of Hanover, Queen of Prussia (1687 – 1757), wife of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia, daughter of King George I of Great Britain

- August Wilhelm of Prussia (1722 – 1758), son of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Emil of Prussia (1758 – 1759), son of August Wilhelm of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Karl Friedrich Albrecht of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1705 – 1762), son of Albrecht Friedrich of Brandenburg-Schwedt, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg

- Heinrich of Prussia (1747 – 1767), son of August Wilhelm of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Christine of Prussia (1772 – 1773), daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Friederike Elisabeth of Prussia (1761 – 1773), daughter of August Ferdinand of Prussia, granddaughter of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Friedrich Heinrich of Prussia (1769 – 1773), son of August Ferdinand of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Friedrich Paul of Prussia (born and died 1776), son of August Ferdinand of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Luise Amalie of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Princess of Prussia (1722 – 1780), wife of August Wilhelm of Prussia

- Anna Amalia of Prussia, Abbess of Quedlinburg (1723 – 1787), daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Ludwig of Prussia (1771 – 1790), son of August Ferdinand of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Unnamed Princess of Prussia (born and died 1794), daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia

- Friedrich Ludwig Karl of Prussia (1773 – 1796), son of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia (1744 – 1797)

- Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern, Queen of Prussia (1715 – 1797), wife of Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia

- Karl Georg of Prussia (1795 – 1798), son of Friedrich Ludwig Karl of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Philippine of Brandenburg-Schwedt, Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel (1745 – 1800), wife of Landgrave Friedrich II of Hesse-Kassel, daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt

- Friederike of Prussia (1799 – 1800), daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia

- Friederike Luise of Hesse-Darmstadt, Queen of Prussia (1751 – 1805), second wife of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Ludwig Ferdinand of Prussia (1772 – 1806), son of August Ferdinand of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Ferdinand of Prussia (1804 – 1806), son of Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia

- Ferdinand of Hesse-Kassel (born and died 1806), son of Wilhelm of Landgrave Hesse-Kassel, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Unnamed Prince (born and died 1806), son of Prince Willem of Orange-Nassau (later King Willem I of the Netherlands) and Wilhelmine of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Wilhelmine of Hesse-Kassel, Princess of Prussia (1726 – 1808), wife of Heinrich of Prussia

- August Ferdinand of Prussia (1730 – 1813), son of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Wilhelm of Prussia (1811 – 1813), son of Wilhelm of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Tassilo of Prussia (1813 – 1814), son of Wilhelm of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Anna Elisabeth Luise of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1738 – 1820), wife August Ferdinand of Prussia

- Unnamed Prince (born and died 1832), son of Prince Albrecht of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia

- Augustus of Prussia (1779 – 1843), son of August Ferdinand of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia

- Heinrich Karl of Prussia (1781 – 1846), son of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Maria Anna Amalie of Hesse-Homburg, Princess of Prussia (1785 – 1846), wife of Wilhelm of Prussia

- Waldemar of Prussia (1817 – 1849), son of Wilhelm of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Wilhelm of Prussia (1783 – 1851), son of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

- Anna of Prussia (born and died 1858), daughter of Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia, great-granddaughter of Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia

- Adalbert of Prussia (1811–1873), son of Wilhelm of Prussia, grandson of Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

*********************

Works Cited

- Berlinerdom.de. 2022. Berliner Dom. [online] Available at: <https://www.berlinerdom.de/> [Accessed 5 March 2022].

- Berlinerdom.de. 2022. GDR period and reconstruction | Berliner Dom. [online] Available at: <https://www.berlinerdom.de/en/visiting/about-the-cathedral/gdr-period-and-reconstruction/> [Accessed 5 March 2022].

- Berlinerdom.de. 2022. The ‘Hohenzollern’ crypt | Berliner Dom. [online] Available at: <https://www.berlinerdom.de/en/visiting/about-the-cathedral/the-hohenzollern-crypt/> [Accessed 5 March 2022].

- De.wikipedia.org. 2022. Berliner Dom – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berliner_Dom> [Accessed 5 March 2022].

- De.wikipedia.org. 2022. Berliner Dom – Hohenzollerngruft – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berliner_Dom#Hohenzollerngruft> [Accessed 5 March 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Berlin Cathedral – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin_Cathedral> [Accessed 5 March 2022].

- Mehl, Scott, 2012. Royal Burial Sites of the Kingdom of Prussia. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/royal-burial-sites/german-royal-burial-sites/royal-burial-sites-of-the-kingdom-of-prussia/> [Accessed 5 March 2022].

- Unofficial Royalty. 2015. Kingdom of Prussia Index. [online] Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/current-monarchies-article-index/german-royals-index/prussian-index/> [Accessed 5 March 2022].

- Williams, Carol, 1999. Germany’s Royals Getting Belated Respect. [online] Los Angeles Times. Available at: <https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-dec-24-mn-47041-story.html> [Accessed 5 March 2022].