by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

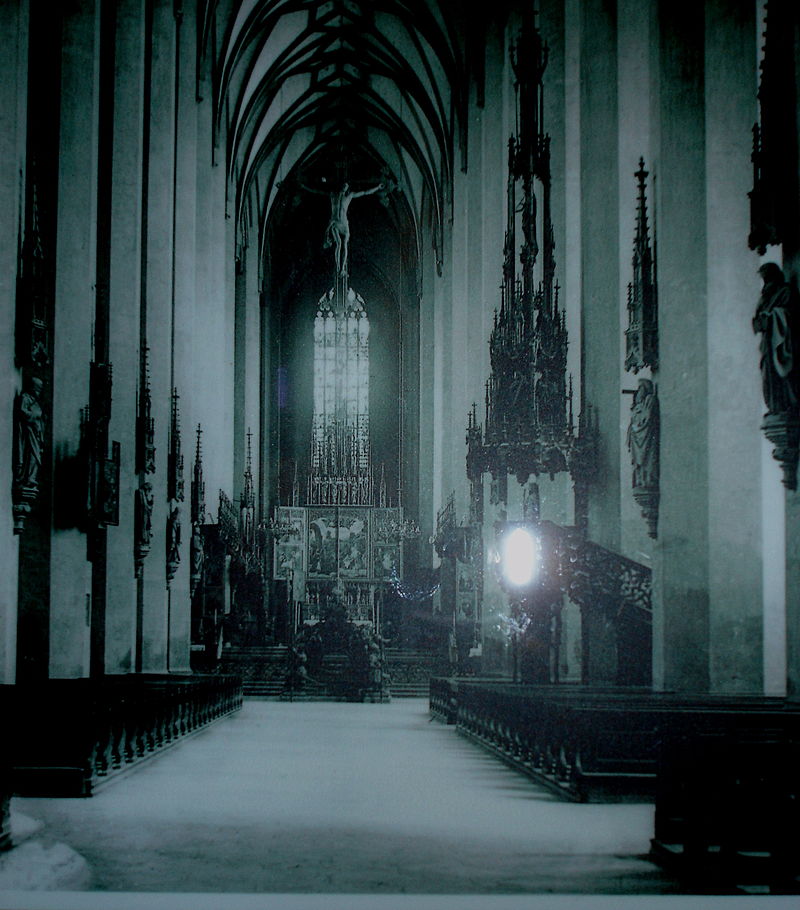

The Basilica of Saint-Denis, which this writer has visited, is a Roman Catholic church in the Paris suburb of Saint-Denis, France. The current Gothic cathedral was built in the 12th century. The Kings of France and their families were buried for centuries at the Basilica of Saint-Denis and it is often referred to as the “royal necropolis of France.” The remains of all but three monarchs of France from the 10th century until 1789 are interred at the Basilica of Saint-Denis. The basilica is named after Saint Denis, a patron saint of France, who became the first Bishop of Paris in the third century. He was decapitated on the hill of Montmartre and is said to have carried his head to the site of the current church, indicating where he wanted to be buried.

Saint Denis holding his head – Notre Dame de Paris; Credit – Wikipedia

A shrine-mausoleum was erected on the site of Saint Denis’ grave in about 313 AD. It was enlarged into a basilica with the addition of tombs and monuments and became a place of pilgrimage during the fifth and sixth centuries. Dagobert, King of the Franks (reigned 628 to 637) re-founded the church as the Abbey of Saint-Denis, a Benedictine monastery, and commissioned a new shrine to house Saint Denis’ remains. Abbot Suger (lived c. 1081 – 1151), a confidant of French kings and Abbot of Saint-Denis from 1122, began work around 1135 to rebuild and enlarge the Abbey of Saint-Denis into the Gothic cathedral we see today.

The interior of the Basilica of St. Denis; Credit – By Rita1234 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8784509

********************

Coronations of the Queen of France

The Coronation in Saint-Denis of Marie de Medici by Peter Paul Rubens; Credit – Wikipedia

Not all Queens of France, wives of the Kings of France, were crowned. A queen’s coronation could take place years after her marriage or her husband’s accession to the throne. Queens of France were crowned either together with their husband at Notre-Dame de Reims, or alone at Sainte-Chapelle or the Basilica of Saint-Denis. Marie de Medici, the wife of King Henri IV, was the last of Queen of France to be crowned. She was crowned ten years after her marriage and her husband was assassinated the day after her coronation.

The Queens of France who were crowned at the Basilica of Saint-Denis include the following:

- February 8, 1492 – Anne, Duchess of Brittany, wife of King Charles VIII and 2nd wife of King Louis XII, the first Queen of France to be crowned at the Basilica of Saint-Denis

- November 5, 1514 – Mary Tudor, 3rd wife of King Louis XII

- May 10, 1517 – Claude of France, Duchess of Brittany, 1st wife of King François I

- March 5, 1531 – Eleanor of Austria, 2nd wife of King François I

- June 10, 1549 – Catherine de’ Medici, wife of King Henri II

- March 25, 1571 – Elisabeth of Austria, wife of King Charles IX

- May 13, 1610 – Marie de Medici, 2nd wife of King Henri IV

********************

Destruction and Restoration

Violation of the royal tombs of Saint-Denis by Hubert Robert (Musée Carnavalet, Paris); Credit – https://uk.tourisme93.com/basilica/desecration-of-the-royal-tombs.html

During the French Revolution, the remains of French royals were desecrated and some tombs and effigies were destroyed. By the decree on August 1, 1793, the National Convention ordered: “The tombs and mausoleums of the former kings, mounted in the Church of Saint-Denis, in temples and in other places, across the entire Republic, will be destroyed.” This occurred systematically from August 1793 – October 1793. The remains of 46 kings, 32 queens, and 63 other royals were thrown into two large pits in the monks’ cemetery adjacent to the Basilica of Saint-Denis and covered in quicklime and soil. A combination of seventy effigies and tombs were saved because of the efforts of archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir who claimed them as artworks for his Museum of French Monuments.

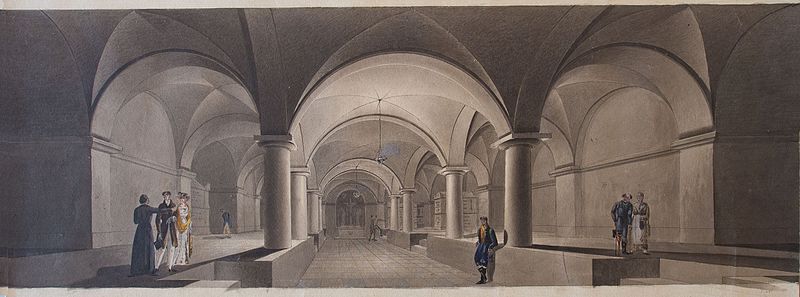

Crypt where Louis VII, Louis de Lorraine, Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette, and Louis XVIII are buried at Saint-Denis; Credit – By Fbrandao.1963 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64407677

Napoleon I, Emperor of the French reopened the Basilica of Saint-Denis in 1806 but left the royal remains in their mass graves. One of the first things King Louis XVIII, a younger brother of the guillotined King Louis XVI, did after the Bourbon Restoration in 1814 was to order a search for the remains of his brother and sister-in-law, King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. They had been originally been buried in the cemetery at the Madeleine Church and covered with quicklime. The few remains that were found were reburied at the Basilica of Saint-Denis on January 21, 1815, the twenty-second anniversary of King Louis XVI’s execution.

Door leading to the crypt where the desecrated royal remains were re-interred at Saint-Denis. The large plaques on either side of the door are engraved with the names of those who were re-interred; Credit – © Susan Flantzer

In 1817, King Louis XVIII ordered the mass graves adjacent to the Basilica of Saint-Denis to be opened but due to the damage from the quicklime, identification of the remains was impossible. The remains were collected into an ossuary, a site serving as the final resting place of human skeletal remains, in the crypt of the basilica. Large marble plates on either side of the gated door leading to the crypt are engraved with the names of those whose remains are buried in the crypt. The seventy effigies and tombs that Alexandre Lenoir saved were returned to the Basilica of Saint-Denis and are now mostly in their original places.

Some of the effigies rescued and preserved by archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir; Credit – © Susan Flantzer

********************

The Heart of Louis-Charles, Dauphin of France, son of King Louis XVI

Louis-Charles, Dauphin of France, son of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, and sometimes called King Louis XVII, died from tuberculosis on June 8, 1795, at the age of ten while imprisoned at the Temple, the remains of a medieval fortress in Paris. He was buried at the Cimetière Sainte-Marguerite in Paris in a grave without any marker. However, before Louis-Charles was buried, an autopsy was performed. Following the tradition of preserving royal hearts, Louis-Charles’s heart was removed and smuggled out during the autopsy by Dr. Philippe-Jean Pelletan, a royalist, who then preserved the heart in alcohol. After the Bourbon Restoration in 1815, Dr. Pellatan offered the heart to Louis-Charles’ paternal uncle King Louis XVIII but he refused because he could not bring himself to believe that it was the heart of his nephew. Following the July Revolution in 1830, Dr. Pelletan’s son found the heart in the remnants of a looted palace and placed it in the crystal urn where it still resides. After the death of Dr. Pelletan’s son in 1879, Eduard Dumont, a relative of Dr. Pelletan’s wife, took possession of the heart.

Louis-Charles’ heart in the crystal urn; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

In 1895, Carlos, Duke of Madrid, the Legitimist claimant to the French throne, accepted the heart from Eduard Dumont. The heart was kept at Schloss Frohsdorf near Vienna, Austria. Upon the death of his father Carlos, Duke of Madrid in 1909, Jaime, Duke of Madrid, the next Legitimist claimant to the French throne, inherited the heart and gave it to his sister Beatriz.

During World War II, Schloss Frohsdorf suffered damage and the heart was rescued by descendants of Carlos, Duke of Madrid and ultimately came into the possession of his granddaughter Princess Marie des Neiges Massimo. In 1975, the princess offered the heart to the Memorial of Saint-Denis in Paris, the organization that oversees the royal graves at the Basilica of St. Denis. The heart was placed in an underground crypt at the basilica where the remains of French royals that were desecrated during the French Revolution were subsequently interred.

In 2004, DNA tests using mitochondrial DNA proved the heart really did belong to Louis-Charles. Comparison samples were taken from descendants of Marie Antoinette’s sisters, members of the Bourbon-Parma family including Queen Anne of Romania who was born a Princess of Bourbon-Parma, and a strand of Marie Antoinette’s hair. With the approval of the French government, the Legitimists organized a ceremony at the Basilica of St. Denis on June 8, 2004, the 209th anniversary of Louis-Charles’ death. His heart was placed in a niche near the graves of his parents Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette whose remains were transferred to the basilica in 1815.

The resting place of Louis-Charles’ heart; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

********************

Royal Burials

*Unofficial Royalty article

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_des_personnes_enterr%C3%A9es_dans_la_basilique_Saint-Denis

- Arnegunde, Queen of the Franks (circa 515/520 – 580), wife of Clotaire I, King of the Franks

- Dagobert I, King of the Franks (circa 603 – 639)

- Nanthilde, Queen of the Franks (circa 610 – 642), wife of Dagobert I

- Clovis II, King of Neustria and Burgundy (633 – 657)

- Clovis III, King of Austrasia (circa 670 – ?)

- Dagobert III, King of the Franks (circa 699 – 715)

- Charles Martel, Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace (circa 688 – 741)

- Pepin the Younger, King of the Franks (circa 714 – 768)

- Bertrada of Laon, Queen of the Franks (born between 710 and 727 – 783), wife of Pepin the Younger

- Ermentrude of Orléans, Queen of the Franks (823 – 869), wife of Charles II the Bald

- Charles II the Bald, Holy Roman Emperor and King of West Francia (823 – 877)

- Louis III, King of West Francia (circa 863/65 – 882)

- Carloman II, King of West Francia (circa 866 – 884)

- Odo, Count of Paris, King of West Francia (circa 857 – 898)

- Hugh the Great, Duke of the Franks, Count of Paris (circa 898 – 956)

- Hugh Capet, King of the Franks (circa 939 – 996)

- Robert II the Pious, King of the Franks (circa 972 – 1031)

- Constance of Provence, Queen of the Franks (circa 986 – 1032), 3rd wife of Robert II the Pious

- Henri I, King of the Franks (1008- 1060)

- Louis VI the Fat, King of the Franks (1081 – 1137)

- Philippe II Auguste, King of France (1165 – 1223)

- Louis VIII, King of France (1187 – 1226)

- Jean Tristand, Count of Valois (1250 – 1270) son of Louis IX

- Saint Louis IX, King of France (1214 – 1270)

- Margaret of France, Duchess of Brabant (1254 – 1271), daughter of Louis IX, 1st wife of John I, Duke of Brabant

- Isabella of Aragon, Queen of France (circa (ca. 1248 – 1271), 1st wife of Philippe III

- Alphonse, Count of Poitiers (1220 – 1271), son of Louis VIII

- Prince Louis of France (1264 – 1276), son of Philippe III

- Philippe III, King of France (1245 – 1285)

- Blanche of France, Duchess of Austria (circa 1282 – 1305), daughter of Philippe III

- Margaret of Provence, Queen of France (1221 – 1295), wife of Louis IX

- Philippe IV, King of France (1268 – 1314)

- Louis X, King of France (1289 – 1316)

- Jean I, King of France (November 15 – 20, 1316)

- Philippe V, King of France (circa 1293 – 1322)

- Clementia of Hungary, Queen of France (1293 – 1328), wife of Louis X, buried in the demolished Church of the Couvent des Jacobins in Paris, effigy is in the Basilica of Saint-Denis

- Princess Marie of France (1327 – 1341), daughter of Charles IV

- Charles II, Count of Alençon (1297 – 1346). brother of Philip VI, buried in the demolished Church of the Couvent des Jacobins in Paris, effigy is in the Basilica of Saint-Denis

- Joan of Burgundy, Queen of France (circa 1293 – 1349), 1st wife of Philippe VI

- Joan II, Queen of Navarre (1312 – 1349), daughter of Louis X, wife of Philip III of Navarre

- Philippe VI, King of France (1293 – 1350)

- Joan I, Countess of Auvergne, Queen of France (1326 – 1360), wife of Jean II

- Jean II, King of France (1319 – 1364)

- Joan of Évreux, Queen of France (1310 – 1371), 3rd wife of Charles IV

- Joan of Valois, Queen of Navarre (1343 – 1373), daughter of Jean II, wife of Charles II of Navarre

- Joanna of Bourbon, Queen of France (1338 – 1378), wife of Charles V

- Isabelle of Valois (1373 – 1377), daughter of Charles V

- Charles V, King of France (1338 – 1380)

- Margaret I, Countess of Burgundy, Countess of Flanders (1310 – 1382), daughter of Philippe V, wife of Louis I, Count of Flanders

- Blanche of France, Duchess of Orléans (1328 – 1393), daughter of Charles IV, wife of Philippe, Duke of Orléans

- Blanche of Navarre, Queen of France (circa 1331 – 1398), 2nd wife of Philippe VI

- Charles VI, King of France (1368 – 1422)

- Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France (circa 1371 – 1435), wife of Charles VI

- Charles VII, King of France (1403 – 1461)

- Marie of Anjou, Queen of France (1404 – 1463), wife of Charles VII

- Charles VIII, King of France* (1470 – 1498)

- Anne, Duchess of Brittany, Queen of France* (1477 – 1514), wife of Charles VIII, 2nd wife of Louis XII

- Louis XII, King of France* (1462 – 1515)

- Claude of France, Duchess of Brittany, Queen of France* (1499 – 1524), 1st wife of François I

- Louise of Savoy, Duchess of Auvergne and Bourbon, Duchess of Nemours (1476 – 1531), mother of François I, wife of Charles of Orléans, Count of Angoulême

- François, Dauphin of France, Duke of Brittany (1518 – 1536), son of François I

- Charles, Duke of Orleans (1522 – 1545), son of François I

- François I, King of France* (1494 – 1547)

- Henri II, King of France* (1519 – 1559)

- François II, King of France* (1544 – 1560)

- Charles IX, King of France* (1550 – 1574)

- Marie Elisabeth of Valois (1572 – 1578), daughter of Charles IX

- François, Duke of Anjou (1555 – 1584), son of Henri II

- Catherine de Medici, Queen of France* (1519 – 1589)

- Henri III, King of France* (1551 – 1589)

- Louise of Lorraine, Queen of France* (1553 – 1601), wife of Henri III

- Henri IV, King of France* (1553 – 1610)

- Nicolas, Duke of Orléans (1604 – 1611), son of Henri IV

- Marguerite of Valois, Queen of France* (1553 – 1615), 1st wife of Henri IV, daughter of Henri II

- Marie of Bourbon, Duchess of Montpensier, Duchess of Orléans (1605 – 1627), 1st wife of Gaston, Duke of Orléans

- Marie de Medici, Queen of France* (1575 – 1642), 2nd wife of Henri IV

- Louis XIII, King of France* (1601 – 1643)

- Gaston, Duke of Orléans* (1608 – 1660), son of Henri IV

- Anne Élisabeth of France (born and died 1662), daughter of Louis XIV

- Marie Anne of France (born and died 1664), daughter of Louis XIV

- Anne of Austria, Queen of France* (1601 – 1666), wife of King XIII

- Henrietta Maria of France, Queen of England* (1609 – 1669), wife of King Charles I of England, daughter of Henri IV

- Henrietta Anna of England, Duchess of Orléans* (1644 – 1670), first wife of Philippe I, Duke of Orléans

- Philippe Charles, Duke of Anjou (1668 – 1671), son of Louis XIV

- Marie Therese of France (1667 – 1672), daughter of Louis XIV

- Marguerite of Lorraine, Duchess of Orléans (1615 – 1672) 2nd wife of Gaston, Duke of Orléans

- Louis François, Duke of Anjou (born and died 1672), son of Louis XIV

- Maria Theresa of Spain, Queen of France* (1638 – 1683), 1st wife of Louis XIV

- Maria Anna of Bavaria, Dauphine of France (1660 – 1690), 1st wife of Louis, Le Grand Dauphin of France

- Philippe I, Duke of Orléans* (1640 – 1701), son of Louis XIII

- Louis, Duke of Brittany (1704 – 1705), son of Louis, Duke of Burgundy, Le Petite Dauphin, grandson of Louis, Le Grand Dauphin of France, great-grandson of Louis XIV

- Louis, Le Grand Dauphin of France* (1661 – 1711), son of Louis XIV

- Maria Adelaide of Savoy, Duchess of Burgundy, Dauphine of France (1685 – 1712), wife of Louis, Duke of Burgundy, Le Petite Dauphin

- Louis, Duke of Burgundy, Le Petite Dauphin* (1682 – 1712), son of Louis, Le Grand Dauphin, grandson of Louis XIV

- Louis, Duke of Brittany (1707 – 1712), son of Louis, Duke of Burgundy, Le Petite Dauphin

- Charles, Duke of Berry (1686 – 1714), son of Louis, Le Grand Dauphin, grandson of Louis XIV

- Louis XIV, King of France* (1638 – 1715)

- Louise Élisabeth of Orléans, Duchess of Berry (1695 – 1719), wife of Charles, Duke of Berry, daughter of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans

- Elizabeth Charlotte (Liselotte) of the Palatinate, Duchess of Orléans* (1652 – 1722), 2nd wife of Philippe of Orléans

- Princess Marie Louise of France (1728 – 1733), daughter of Louis XV

- Philippe Louis, Duke of Anjou (1730 – 1733), son of Louis XV

- Princess Marie Therese of France (1746 – 1748), daughter of Louis, Dauphin of France, sister of Louis XVI

- Princess Anne Henriette of France (1727 – 1752), daughter of Louis XV

- Stillborn princess (1752), daughter of Louis, Dauphin of France, sister of Louis XVI

- Xavier, Duke of Aquitaine (1753 – 1754), son of Louis, Dauphin of France, brother of Louis XVI

- Princess Marie Zephyrine of France (1750 – 1755), daughter of Louis, Dauphin of France, sister of Louis XVI

- Louise Élisabeth of France, Duchess of Parma (1727 – 1759), daughter of Louis XV, wife of Infante Philip, Duke of Parma

- Louis Joseph, Duke of Burgundy (1751 – 1761), son of Louis, Dauphin of France, brother of Louis XVI

- Marie Leszczyńska, Queen of France* (1703 – 1768), wife of Louis XV

- Louis XV, King of France* (1710 – 1774)

- Princess Sophie Philippine of France (1734 – 1782), daughter of Louis XV

- Marie Thérèse, Mademoiselle d’Angoulême born and died 1783), daughter of Charles X

- Sophie, Mademoiselle d’Artois (1776 – 1783), daughter of Charles X

- Princess Sophie Hélène Béatrix of France (1786 – 1787), daughter of Louis XVI

- Princess Louise Marie of France (1737 – 1787), daughter of Louis XV, a nun Carmelite convent at Saint-Denis under the name Sister Thérèse of Saint Augustine

- Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France (1781 – 1789), son of Louis XVI

- Louis XVI, King of France* (1754 – 1793)

- Maria Antonia of Austria, Queen Marie Antoinette of France* (1755 – 1793), wife of Louis XVI

- Louis-Charles, Dauphin of France* (titular King Louis XVII of France) (1785 – 1795), son of Louis XVI

- Princess Victoire Louise of France (1733 – 1799), daughter of Louis XV

- Princess Marie Adélaïde of France (1732 – 1800), daughter of Louis XV

- Princess Louise Élisabeth d’Artois (born and died 1817), daughter of Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, grandson of Charles X

- Louis Joseph of Bourbon, Prince de Condé (1736 – 1818), great-grandson of Louis XIV

- Prince Louis of Artois (born and died 1818), son of Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, grandson of Charles X

- Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry (1778 – 1820), son of Charles X

- Louis XVIII, King of France* (1755 – 1824)

- Louis Henri Joseph of Bourbon, Prince of Condé, Duke of Bourbon (1756 – 1830), son of Louis Joseph of Bourbon, Prince de Condé

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

- Official Website: Cathedral Basilica of Saint-Denis

- Unofficial Royalty: House of Valois Burials

- Unofficial Royalty: House of Bourbon, House of Bonaparte, House of Orléans Burials

- For a map of the tombs at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, see UK Tourism: Map of the tombs in the Basilica of Saint-Denis

Works Cited

- Basilique cathédrale de Saint-Denis. 2022. Basilique cathédrale de Saint-Denis. [online] Available at: <http://www.saint-denis-basilique.fr/en/> [Accessed 14 March 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Basilica of Saint-Denis – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_Saint-Denis> [Accessed 14 March 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2018. French Royal Burial Sites – House of Bourbon, House of Bonaparte, House of Orléans. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/current-monarchies-article-index/french-royal-index/french-burial-sites-house-of-bourbon-house-of-bonaparte-house-of-orleans/> [Accessed 14 March 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2019. French Royal Burial Sites – House of Valois. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/french-royal-burial-sites-house-of-valois/> [Accessed 14 March 2022].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. 2022. Basilique Saint-Denis — Wikipédia. [online] Available at: <https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilique_Saint-Denis> [Accessed 14 March 2022].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. 2022. Liste des personnes enterrées dans la basilique Saint-Denis — Wikipédia. [online] Available at: <https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_des_personnes_enterr%C3%A9es_dans_la_basilique_Saint-Denis> [Accessed 14 March 2022].