by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg, Russia; Photo Credit – By Andrew Shiva / Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51961358

On an island in the Neva River that flows through St. Petersburg, Russia is the Peter and Paul Fortress, the original citadel of the city established by Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia in 1703. Inside the fortress is a Russian Orthodox cathedral, the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul, which this writer has visited. The cathedral was built during the reign of Peter I (the Great) and designed by Domenico Trezzini, a Swiss architect who designed many of the first buildings in St. Petersburg. The Peter and Paul Cathedral is the burial place of all but two of the Russian sovereign emperors and empresses from Peter the Great to Nicholas II, who was finally laid to rest in July 1998. Only Peter II and Ivan VI are not buried at the Peter and Paul Cathedral.

********************

History of the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul in St. Petersburg, Russia

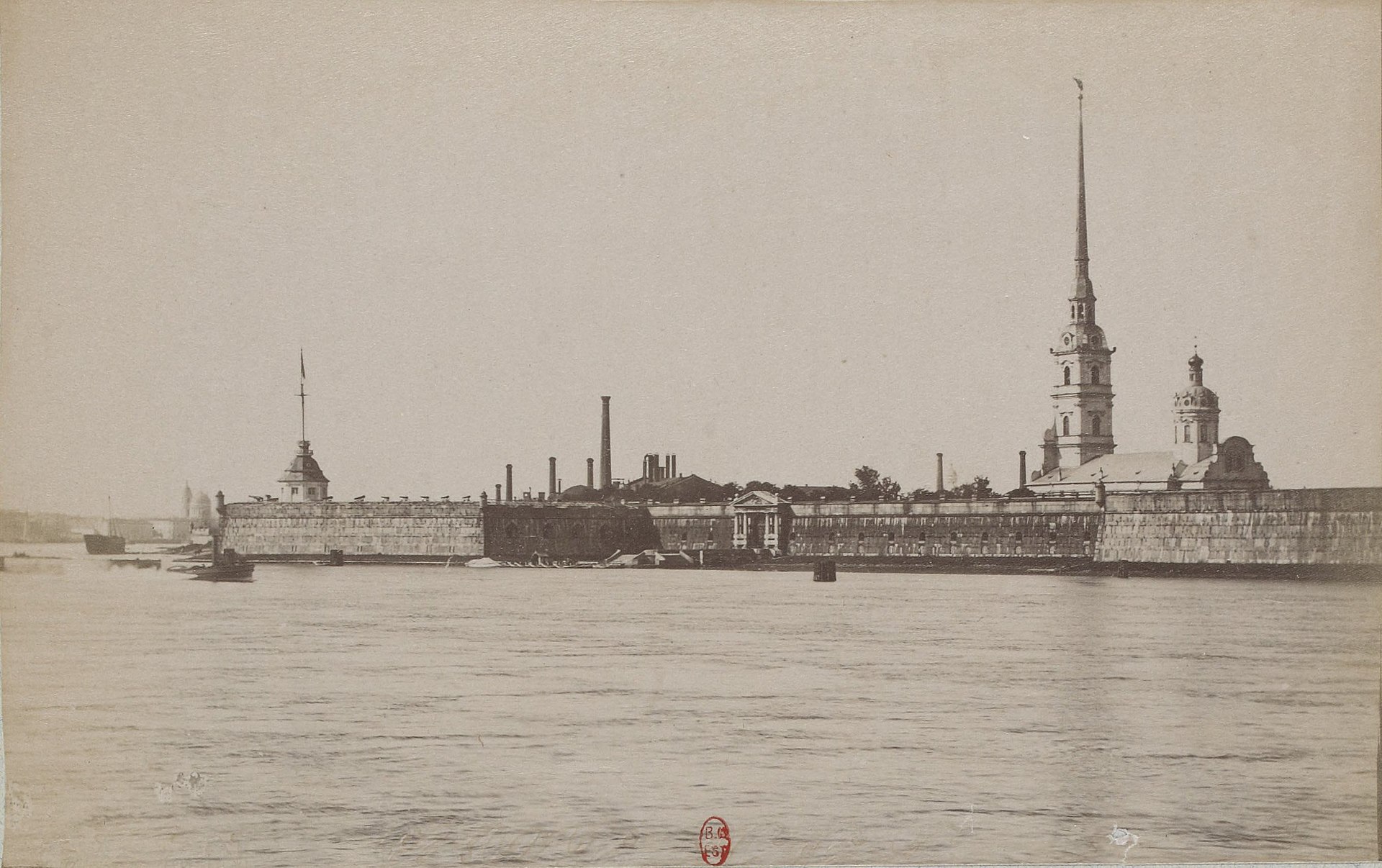

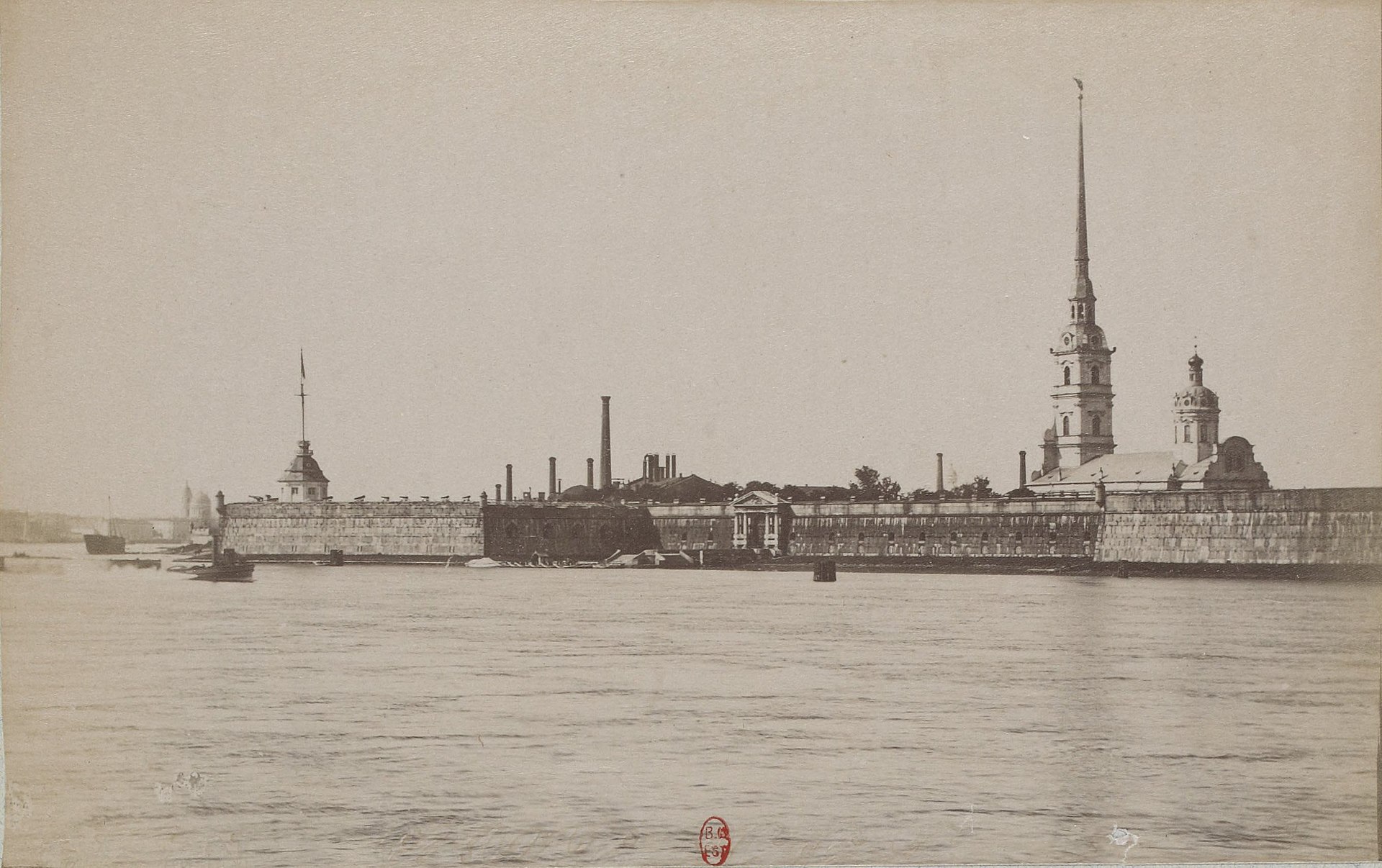

View of the Peter and Paul Fortress from the Neva River in the 1870s; Credit – Wikipedia

From 1703 to 1704, Peter I (the Great) had a wooden church, used for military purposes, built in the Peter and Paul Fortress. To strengthen the position of his new capital city of St. Petersburg among the cities of Russia, Peter the Great wanted to build a church that would be taller than the Ivan the Great Bell Tower (the tallest structure in the Moscow Kremlin) and the Menshikov Tower of the Church of Archangel Gabriel in Moscow. He wanted the new church to become the most significant building in St. Petersburg and be located in the heart of the Peter and Paul Fortress. Swiss architect Domenico Trezzini was commissioned to design a church that was intended to be the main cathedral of the Russian Empire and the burial place of the House of Romanov. Construction work began in 1712. When Peter the Great died in 1725, only the foundations and the tower were standing. The cathedral was completed in 1733 after twenty-one years of construction. A cathedral in Russia could mean the seat of a bishop or a large or important church. Peter and Paul Cathedral, an important church, was the cathedral church of St. Petersburg until 1858 when St. Isaac Cathedral became St. Petersburg’s cathedral. At that time, Peter and Paul Cathedral came under the jurisdiction of the Russian imperial court.

The original wooden spire was rebuilt after a lightning strike in 1756. In 1773, the Chapel of Saint Catherine, dedicated to Saint Catherine of Alexandria, now the burial site of Nicholas II, his family, their doctor, and their three servants, was completed. In 1777, the spire was damaged by a storm. Restoration work was carried out by the architect Peter Paton and a new angel and cross was made by Antonio Rinaldi. In 1830, roofer Pyotr Teluschkin became famous when he used a rope ladder to climb the spire to replace the angel and cross which had been that had been damaged by lightning. The spire was rebuilt in metal in 1858 and covered with gilded copper plates.

In 1919, the Soviet regime closed the Peter and Paul Cathedral, and then in 1924, it was turned into a museum. Most of the valuable items of the late 17th – early 18th centuries such as silver items, books, vestments, and icons were given to museums. During World War II, the Peter and Paul Cathedral was badly damaged. In 1952, the facades were restored, and then from 1956 to 1957, the interior was restored. Peter and Paul Cathedral is still officially a museum, and in 1954, the cathedral came under the jurisdiction of the State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg.

Since the 1990s, memorial services for Russian emperors and empresses have been held on the date of their deaths. Other religious services resumed in 2000. The first Easter service since 1917 was held in 2008. For the 300th anniversary in 2012, the cathedral was extensively restored.

********************

The Exterior of the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul

Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul; Credit – Автор: Никонико962 – собственная работа, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81987560

The Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Pau is rectangular in shape, with a dome on the eastern end and a bell tower with a spire on the western entrance. The exterior of the Peter and Paul Cathedral does not have the five typical domes representing Jesus Christ and the Four Evangelists as do most other Orthodox churches. Instead, the dominant part of the cathedral’s exterior is the bell tower. The first three tiers of the bell tower provide a smooth transition from the main part of the cathedral to the spire. The base of the spire is an octagonal structure with narrow vertical openings topped by an octagonal golden crown.

The angel on the spire of the Peter and Paul Cathedral; Credit – Автор: Ad Meskens – собственная работа, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=77086740

Atop the 131-foot/40-meter spire is a weather vane in the shape of an angel (height: 10.4 feet/3.2 meters, wingspan: 12.4 feet/3.8 meters) revolving around a 21-foot/6.4-meter-tall cross on its gilded spire. The 402-foot/122.5 meter Peter and Paul Cathedral remained St. Petersburg’s tallest building, as ordered by Peter the Great, until the Construction of the municipal television tower in 1962. However, the Peter and Paul Cathedral still has the world’s tallest Orthodox bell tower.

********************

The Interior of the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul

The nave of the Peter and Paul Cathedral looking toward the iconostasis; Credit – By Deror avi – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8367790

Orthodox churches are set up differently than other Christian churches. They are divided into three main parts: the narthex, the nave, and the sanctuary. The narthex is the connection between the church and the outside world. It used to be the practice that non-Orthodox people had to remain in the narthex but this practice has mostly fallen into disuse. The congregation stands in the nave during services. Traditionally there is no sitting during Orthodox services and so Orthodox churches usually do not have pews or chairs.

Ceiling fresco paintings; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

The Peter and Paul Cathedral is a hall church, with a nave and side aisles. The interior of the cathedral is divided into three parts by pillars, painted to imitate marble. The ceiling vaults are decorated with multicolored fresco paintings and gilded moldings. The cathedral is lit by twelve large windows. Although a cathedral because of its importance, the Peter and Paul Cathedral is nowhere near the size of other cathedrals this writer has visited. There are no pews in the nave but the pillars and tombs combined with lots of people made moving around (and not losing your tour guide) difficult.

There’s our tour guide with the pulpit and lots of people in the background; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

In Orthodox Christianity, an iconostasis is a wall of icons, religious paintings, that divides the sanctuary from the nave. The sanctuary is where the Eucharist or Divine Liturgy is performed behind the iconostasis. The iconostasis usually has three doors, one in the middle and one on either side. The middle doors are traditionally called the Royal Doors and are only used by the clergy.

The iconostasis; Credit – By Poudou99 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57887255

The carved, gilded 65-foot/20-meter high iconostasis was made from 1722 to 1726 in the Kremlin Armory in Moscow, then brought in parts to St. Petersburg, and mounted in the Peter and Paul Cathedral. All decorative details and sculptural elements of the iconostasis were carved from linden wood and the frame of the iconostasis was made from larch wood.

Some of the icons on the iconostasis

Forty-three icons for the iconostasis were painted from 1726 to 1729 by Moscow icon painters and include images of the patron saints of St. Petersburg: St. Alexander Nevsky, the Apostles Peter and Paul, holy princes and princesses from the Rurik dynasty: Prince Vladimir I (the Great), Princess Olga, and the brothers and martyrs Prince Boris of Rostov and Prince Gleb of Murom.

The iconostasis rising into the cathedral’s dome; Credit – CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=136587

The central part of the iconostasis is designed in the form of the triumphal arch that spans the Royal Doors and rises into the space beneath the dome to a height of 66 feet/20 meters. Near the iconostasis is a pulpit to the left, and the Tsar’s Place to the right, a special spot where the Emperor stood when there was a service.

The Tsar’s Place; Credit – By Perfektangelll – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21354345

********************

Burials in the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul

The burial service for Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia in 1894

Before the building of the Peter and Paul Cathedral, male rulers of the Rurik dynasty and the early Romanov dynasty along with close male relatives and some Russian noblemen were interred at the Archangel Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin. Likewise, women of the Rurik dynasty and women of the early Romanov dynasty along with some Russian noblewomen were interred at the Ascension Cathedral of the Ascension Convent in the Moscow Kremlin.

Several members of the Romanov family who died before the Peter and Paul Cathedral was completed were interred in the unfinished cathedral under the bell tower or in the entrance to the cathedral. After the death of Peter I (the Great) in 1725, his coffin was placed in a temporary chapel in the unfinished cathedral. He was interred in his final resting place on May 29, 1731. In 1831, Nicholas I ordered that his brother Grand Duke Konstantine Pavlovich be buried in the cathedral. Since that time, close relatives of the emperors began to be buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral.

Graves of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, his wife Charlotte Christine of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Tsarevna of Russia, and his aunt Tsarevna Maria Alexeievna – They died before the cathedral was finished and were interred at the entrance to the cathedral. The original white marble tombstones still mark their graves; Credit – Wikipedia

Originally, graves were marked by white marble tombstones as seen in the above photo. In 1865, all the tombstones were replaced with the white marble sarcophagi with a large bronze cross coated in gold as seen in the photo below.

Sarcophagi in the Peter and Paul Cathedral; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

The sarcophagi of emperors and empresses have four bronze emblems of the Russian Empire at four corners as seen in the photo below of the sarcophagus of Peter I (the Great).

Sarcophagus of Peter I (the Great); Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

By order of Alexander III, new sarcophagi were made for his parents: the sarcophagus of Alexander II from green Altai jasper and the sarcophagus of Empress Maria Alexandrovna from pink Urals rhodonite as seen in the photo below.

Sarcophagi of Alexander II (left) and his first wife Maria Feodorovna (right); Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

Interred in the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul

Peter and Paul Cathedral – Row 1 left to right: Tombs of Elizabeth I, Catherine I, Peter I; Row 2 left to right: Tombs of Catherine II, Peter III, Anna I; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

- Grand Duchess Catherine Petrovna (1706 – 1708), daughter of Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia

- Marfa Matveyevna Apraksina, Tsaritsa of Russia (1664 -1716), second wife of Feodor III, Tsar of All Russia

- Grand Duchess Maria Petrovna (1713 – 1715), daughter of Peter I (the Great)

- Grand Duchess Margarita Petrovna (1714 – 1715), daughter of Peter I (the Great)

- Charlotte Christine of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Tsarevna of Russia (1694 – 1715), wife of Alexei Petrovich, Tsarevich of Russia (son of Peter I (the Great)

- Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich (born and died 1717), son of Peter I (the Great)

- Alexei Petrovich, Tsarevich of Russia (1690 – 1718), son of Peter I (the Great)

- Tsarevna Maria Alexeievna (1660–1723), daughter of Alexei I, Tsar of All Russia

- Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia (1672 – 1725)

- Grand Duchess Natalia Petrovna (1718 – 1725), daughter of Peter I (the Great)

- Catherine I, Empress of All Russia (1684 – 1727), second wife of Peter I and Empress in her own right

- Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna (1708 – 1728), daughter of Peter I (the Great) and wife of Karl Friedrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp

- Anna, Empress of All Russia (1693 – 1740)

- Elizabeth, Empress of All Russia (1709 – 1762)

- Peter III, Emperor of All Russia (1728 – 1762)

- Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia, born Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst (1729 – 1796), wife of Peter III

- Paul I, Emperor of All Russia (1754- 1801)

- Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia (1777 – 1825)

- Elizabeth Alexeievna, Empress of All Russia, born Louise of Baden (1779 – 1826) wife of Alexander I

- Maria Feodorovna, Empress of All Russia, born Sophia Dorothea of Württemberg, second wife of Paul I

- Grand Duke Konstantine Pavlovich (1779 – 1831), son of Paul I

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Mikhailovna (1831 – 1832), daughter of Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich

- Grand Duchess Anna Mikhailovna (1834 – 1836), daughter of Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich

- Grand Duchess Maria Mikhailovna (1825 – 1846), daughter of Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Alexandrovna (1842 – 1849), daughter of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia

- Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich (1798 – 1849), son of Paul I

Nicholas I, Emperor of All Russia (1796 – 1855)

- Alexandra Feodorovna, Empress of All Russia, born Charlotte of Prussia (1798 – 1860), wife of Nicholas I

- Nicholas Alexandrovich, Tsarevich of Russia (1843 – 1865), son of Alexander II

- Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich (1869 – 1870), son of Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia

- Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, born Charlotte of Württemberg (1807 – 1873), wife of Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich

- Maria Alexandrovna, Empress of All Russia, born Marie of Hesse and by Rhine (1824 – 1880), first wife of Alexander II

- Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia (1818 – 1881)

- Grand Duchess Olga Feodorovna, born Cecilie of Baden (1839 – 1891), wife of Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich

- Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich (1831 – 1891), son of Nicholas I

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna, born Alexandra of Greece and Denmark (1870 – 1891), first wife of Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich, transferred to the Royal Cemetery on the grounds of Tatoi Palace in Greece in 1939

- Grand Duchess Catherine Mikhailovna (1827 – 1894), daughter of Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich, wife of Duke Georg August of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia (1845 – 1894)

- Grand Duke Alexei Mikhailovich (1875 – 1895), son of Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich

- Grand Duke George Alexandrovich (1871 – 1899), Alexander III

- Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich (1847 – 1909), son of Alexander II

- Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich (1832 – 1909), son of Nicholas I

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna, born Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg (1830 – 1911), wife of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich

- Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia (1868 – 1918), interred on July 17, 1998

- Alexandra Feodorovna, Empress of All Russia, born Alix of Hesse and by Rhine (1872 – 1918), wife of Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia, interred July 17, 1998

- Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna (1895 – 1918), daughter of Nicholas II, interred on July 17, 1998

- Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna (1897 – 1918), daughter of Nicholas II, interred on July 17, 1998

- Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna (1901 – 1918), daughter of Nicholas II, interred on July 17, 1998

- Dr. Yevgeny Sergeyevich Botkin (1865 – 1918), court doctor to the family of Nicholas II

- Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov (1872 – 1918), cook to the family of Nicholas II

- Alexei Yegorovich Trupp (1856 – 1918), footman to the family of Nicholas II

- Anna Stepanovna Demidova (1878 – 1918), maid to the family of Nicholas II

- Maria Feodorovna, Empress of All Russia, born Dagmar of Denmark (1847 – 1928), wife of Alexander III, transferred from Roskilde Cathedral in Roskilde, Denmark in 2006

********************

Reburials at the Peter and Paul Cathedral

St. Catherine Chapel, the burial site of Nicholas II, his family and his servants; Credit – By Dr Graham Beards – Own work, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13260852

Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia, his wife Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, born Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, and their five children, along with three of their most loyal servants and the court doctor, were shot to death by a firing squad on July 17, 1918, at the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, Siberia, Russia. The bodies were taken to a remote site north of Yekaterinburg. The initial plan was to burn the bodies but when this took longer than expected, the bodies were buried in an unmarked pit. After acid was poured on the bodies, they were covered with railroad ties, and the pit was smoothed over with dirt and ash.

In 1934, Yakov Yurovsky, the commandant of the Ipatiev House, produced an account of the execution and disposal of the bodies. His account later matched the remains of nine bodies found north of Yekaterinburg in 1991. In 1994, when the bodies of the Romanovs were exhumed, two were missing – one daughter, either Maria or Anastasia, and Alexei, the hemophiliac son. The remains of the nine bodies recovered were confirmed as those of the three servants, Dr. Botkin, Nicholas, Alexandra, and three of their daughters. The remains of Olga and Tatiana were definitely identified based on the expected skeletal structure of young women of their age. The remains of the third daughter were either Maria or Anastasia.

The family and their servants were canonized as new martyrs in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia in 1981, and as passion bearers in the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000. The formal burial of Nicholas, Alexandra, Olga, Tatiana, Anastasia, Dr. Botkin, and the three servants took place on July 17, 1998, the 80th anniversary of their deaths, in St. Catherine Chapel at the Peter and Paul Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. Boris Yeltsin, President of Russia, many Romanov family members, and family members of Dr. Botkin and the servants attended the ceremony. Prince Michael of Kent represented his first cousin Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom. Three of his grandparents were first cousins of Nicholas II.

Until 2009, it was not entirely clear whether the remains of Maria or Anastasia were missing. On August 24, 2007, a Russian team of archaeologists announced that they had found the remains of Alexei and his missing sister in July 2007. In 2009, DNA and skeletal analysis identified the remains found in 2007 as Alexei and his sister Maria. In addition, it determined that the royal hemophilia was the rare, severe form of hemophilia, known as Hemophilia B or Christmas disease. The results showed that Alexei had Hemophilia B and that his mother Empress Alexandra and his sister Anastasia were carriers of the disease. The remains of Alexei and Maria have not yet been buried. The Russian Orthodox Church has questioned whether the remains are authentic and blocked the burial.

Sarcophagus of Empress Maria Feodorovna; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

Maria Feodorovna, Empress of All Russia, born Princess Dagmar of Denmark, wife of Alexander III and mother of Nicholas II, died on October 13, 1928, at Hvidøre, the holiday villa she had purchased with her sister Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom in 1906, near Copenhagen, Denmark. Following services in Copenhagen’s Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Church, Maria Feodorovna was interred in the crypt of the Christian IX Chapel at Roskilde Cathedral, the traditional burial place of the Danish royal family in Roskilde, Denmark. She had wished that at some point in time she could be buried with her husband.

The coffin of Maria Feodorovna being lowered into the crypt

In 2005, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed, along with their governments, that Maria Feodorovna’s wish should be fulfilled. Her remains were transported to St. Petersburg. Following a service at Saint Isaac’s Cathedral, she was interred next to her husband Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia in the Peter and Paul Cathedral on September 28, 2006.

********************

Originally Buried at the Peter and Paul Cathedral

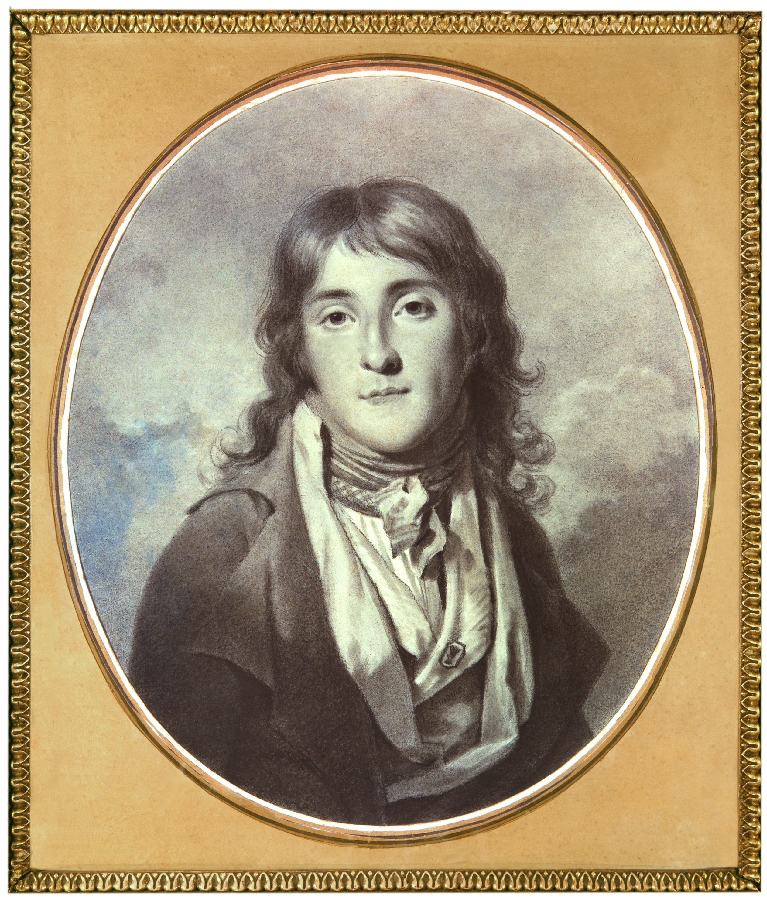

Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna; Credit – Wikipedia

Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna was the first wife of Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich. While pregnant with her second child, Alexandra collapsed in the middle of a ball with violent labor pains, gave birth prematurely to a son, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and then lapsed into a coma. Alexandra did not recover consciousness and died six days later on September 24, 1891, at the age of 21. Originally, it was thought that a fall caused her premature labor. However, an autopsy showed that Alexandra’s premature labor was caused by eclampsia, a condition that causes a pregnant woman, usually previously diagnosed with preeclampsia (high blood pressure and protein in the urine), to develop seizures or coma. Nephritis, a kidney disorder, and heart damage were also detected.

In 1939, at the request of Alexandra’s nephew King George II of Greece and the Greek government, the Soviet government allowed Alexandra’s remains to be transferred to Greece. Her coffin was removed from the Peter and Paul Cathedral, put aboard a Greek ship, and brought back to Greece where it was reinterred at the traditional burial site of the Greek royal family, the Royal Cemetery on the grounds of Tatoi Palace. Alexandra’s original marble tomb in the Peter and Paul Cathedral remains at its original site and is the only tomb in the cathedral over an empty grave.

********************

The Grand Ducal Mausoleum

The Grand Ducal Mausoleum; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

The Grand Ducal Mausoleum is located on the left side of the Peter and Paul Cathedral. There is a corridor between the mausoleum and the cathedral. Because of decreasing room for burials at the Peter and Paul Cathedral, the Grand Ducal Mausoleum was constructed. It was designed by architect David Ivanovich Grimm in 1896. After Grimm’s death in 1898, architects Antony Tomishko and Leon Benois took over the project. The mausoleum, completed in 1908, was expected to hold up to sixty burials but by the time of the Russian Revolution, there had been only thirteen burials. For each burial, a marble slab was placed in the floor, on which was inscribed the title, name, date of birth and death, and date of burial.

Graves of Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna (left) and Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich (right) in the Grand Ducal Mausoleum; Credit – www.pointurier.org

After the Russian Revolution, much of the interior of the mausoleum was damaged due to plans to turn it into a museum and also during World War II due to the German Siege of Leningrad, as St. Petersburg was called during the Soviet regime. Major restoration work occurred in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1980s. In 2006, the stained glass window depicting the resurrection of Jesus was recreated. In 2008, the restoration of the facade and roof was carried out. The Grand Ducal Mausoleum opened to the public in September 2016.

Interior of the Grand Ducal Mausoleum with several burial slabs; Credit – By Poudou99 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57886041

The remains of those who died before the completion of the Grand Ducal Mausoleum in 1908 were transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral. The remains of Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich and his wife Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna (Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria) were transferred from Coburg, Germany in 1995. Their only son Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich was interred in the Grand Ducal Mausoleum after his death in 1992 as was his wife Leonida Georgievna Bagration-Mukhranskaya, Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna after her death in 2010.

********************

Interred in the Grand Ducal Mausoleum

The funeral of Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna in 2010 in the Peter and Paul Cathedral before the burial in the Grand Ducal Mausoleum

- Duchess Alexandra Maximilianovna of Leuchtenberg (1840 – 1843), daughter of Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna and Maximilian de Beauharnais, 3rd Duke of Leuchtenberg, transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1908

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna (1825 – 1844), daughter of Nicholas I, wife of Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel, transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1908

- Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna (1819 – 1876), daughter of Nicholas I, wife of Maximilian de Beauharnais, 3rd Duke of Leuchtenberg, Count Grigori Stroganov, transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1908

- Grand Duke Alexander Vladimirovich (1875 – 1877), son of Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1908

- Prince Sergei Maximilianovich Romanovsky, Duke of Leuchtenberg (1849 – 1877), son of Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna and Maximilian de Beauharnais, 3rd Duke of Leuchtenberg, transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1908

- Grand Duke Vyacheslav Konstantinovich (1862 – 1879), son of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1908

- Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich (1827 – 1892), son of Nicholas I, transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1908

- Princess Natalia Konstantinovna (born and died 1905), daughter of Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, transferred from the Peter and Paul Cathedral in 1908

- Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich (1850 – 1908), son of Alexander II

- Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich (1847 – 1909), son of Alexander II

- Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg, Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna (1830 – 1911), wife of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich

- Prince George Maximilianovich Romanowsky, 6th Duke of Leuchtenberg (1852 – 1912), son of of Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna and Maximilian de Beauharnais, 3rd Duke of Leuchtenberg

- Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (1858 – 1915), son of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich

- Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna, Victoria Melita of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1876 – 1936) wife of Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, transferred from the Ducal Mausoleum at Glockenburg Cemetery in Coburg, Germany in 1995

- Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich (1876 – 1938), son of Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich, transferred from the Ducal Mausoleum at Glockenburg Cemetery in Coburg, Germany in 1995

- Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich (1917 – 1992), son of Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich

- Leonida Georgievna Bagration-Mukhranskaya, Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna (1914 – 2010), wife of Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich

********************

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. 2022. Peter-und-Paul-Kathedrale (Sankt Petersburg) – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter-und-Paul-Kathedrale_(Sankt_Petersburg)> [Accessed 20 April 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saints_Peter_and_Paul_Cathedral,_Saint_Petersburg> [Accessed 20 April 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2017. Romanov Burial Sites. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/royal-burial-sites/romanov-burial-sites/> [Accessed 20 April 2022].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. 2022. Mausolée grand-ducal de Saint-Pétersbourg — Wikipédia. [online] Available at: <https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mausol%C3%A9e_grand-ducal_de_Saint-P%C3%A9tersbourg> [Accessed 20 April 2022].

- Pt.wikipedia.org. 2022. Jazigo dos Grão-Duques – Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre. [online] Available at: <https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazigo_dos_Gr%C3%A3o-Duques> [Accessed 20 April 2022].

- Ru.wikipedia.org. 2022. Петропавловский собор — Википедия. [online] Available at: <https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9F%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BF%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%BE%D1%80> [Accessed 20 April 2022].

- Spbmuseum.ru. 2022. Петропавловский собор и Великокняжеская усыпальница. [online] Available at: <https://www.spbmuseum.ru/exhibits_and_exhibitions/92/1316/> [Accessed 20 April 2022].