by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

The Hawaiian Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean, were originally divided into several independent chiefdoms. The Kingdom of Hawaii was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great of the independent island of Hawaii, conquered the independent islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, and Lanai, and unified them under one government and ruled as Kamehameha I, King of the Hawaiian Islands. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauai and Niihau voluntarily joined the Kingdom of Hawaii. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

In 1778, British explorer James Cook visited the islands. This led to increased trade and the introduction of new technologies and ideas. In the mid-19th century, American influence in Hawaii dramatically increased when American merchants, missionaries, and settlers arrived on the islands. Protestant missionaries converted most of the native people to Christianity. Merchants set up sugar plantations and the United States Navy established a base at Pearl Harbor. The newcomers brought diseases that were new to the indigenous people including influenza, measles, smallpox, syphilis, tuberculosis, and whooping cough. At the time of James Cook’s arrival in 1778, the indigenous Hawaiian population is estimated to have been between 250,000 and 800,000. By 1890, the indigenous Hawaiian population declined had to less than 40,000.

In 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliʻuokalani, her cabinet, and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This led to the 1898 annexation of Hawaii as a United States territory. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States.

In 1993, one hundred years after the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown, the United States Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution which “acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum”. As a result, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom in Hawaii, was established along with ongoing efforts to redress the indigenous Hawaiian population.

********************

Kamehameha II, King of the Hawaiian Islands; Credit – Wikipedia

Born Prince Liholiho in November 1797, in Hilo, Kingdom of Hawaii, Kamehameha II, King of the Hawaiian Islands was the eldest of the three children and the elder of the two sons of Kamehameha I the Great, King of the Hawaiian Islands and his chief wife Keōpūolani. King Kamehameha I had many wives and many children. The exact number is debated because documents that recorded the names of his wives were destroyed. While he had many wives and children, only his children from his highest-ranking wife Keōpūolani succeeded him to the throne.

Kamehameha II had two full siblings:

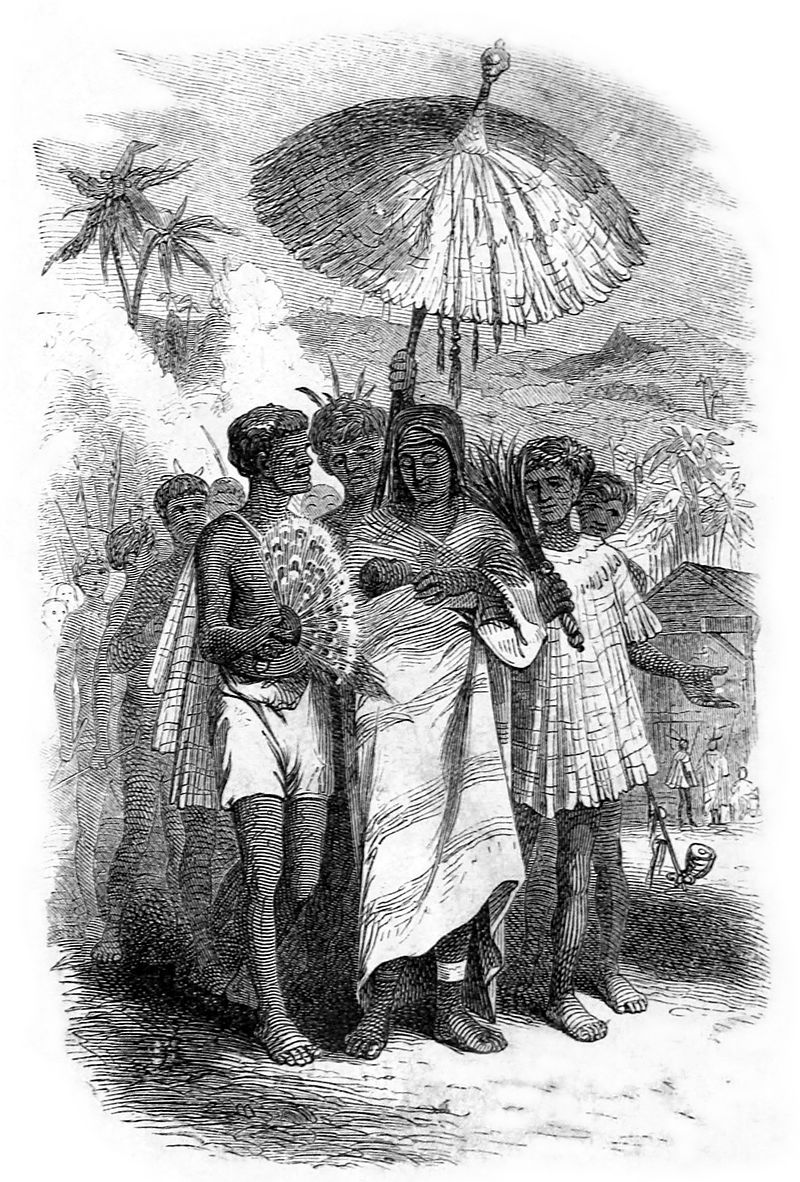

Queen Kaʻahumanu, Kamehameha II’s official guardian and later his co-regent; Credit – Wikipedia

Kamehameha II’s care was entrusted to his father’s trusted servant Hanapi. However, after several months, he was taken back by his maternal grandmother Queen Kekuʻiapoiwa Liliha because she felt he was not getting the proper care. Kamehameha I then put his son in the care of Queen Kaʻahumanu, his favorite wife, who was appointed as Kamehameha II’s official guardian.

Jean Baptiste Rives, a Frenchman who arrived in the Kingdom of Hawaii in the early 19th century, taught the royal princes some English and French and became a close friend of Kamehameha II. He also had three other close companions. Charles Kanaʻina was an aliʻi (hereditary noble) of the Kingdom of Hawaii who served on both the Privy Counsel and in the House of Nobles. Mataio Kekūanaōʻa was governor of the island of Oʻahu, held the office of Kuhina Nui (equivalent of the 19th-century European office of Prime Minister), and was the father of two kings, Kamehameha IV and Kamehameha V. Gideon Peleioholani Laanu was a Hawaiian chief and the great nephew of Kamehameha I.

Kamāmalu, Kamehameha II’s favorite wife, his half-sister; Credit – Wikipedia

Kamehameha II continued the practice of polygamy and had five wives but none of the marriages produced children:

- Kamāmalu (circa 1802 – 1824), Kamehameha II’s favorite wife, his half-sister

- Kīnaʻu (circa 1805 – 1839), Kamehameha II’s half-sister

- Kekāuluohi (1794 – 1845), Kamehameha II’s cousin

- Pauahi (circa 1804–1826), often referred to as often referred to as Kalanipauahi, Kamehameha II’s niece

- Kekauʻōnohi (circa 1805 – 1851), Kamehameha II’s niece

On May 14, 1819, Kamehameha I, King of the Hawaiian Islands died and 22-year-old Kamehameha II became King of the Hawaiian Islands. However, Queen Kaʻahumanu, who had been Kamehameha II’s official guardian, had no intention of giving up her power. When she first saw Kamehameha II after his father’s death, she was wearing Kamehameha I’s royal red cape and announced to the surprised young king, “We two shall rule the land.” The council of advisors agreed and created her Kuhina Nui. Her role was similar to a co-regent or modern-day prime minister. Queen Kaʻahumanu held the administrative power while Kamehameha II was forced to take on just a ceremonial role. Kaʻahumanu ruled as co-regent during the reigns of both Kamehameha II and his brother and successor Kamehameha III, until she died in 1832.

Kamehameha II’s reign is best known for the ‘Ai Noa, the elimination of the Hawaiian kapu system in October 1819. Kapu was the ancient Hawaiian code of conduct of laws and regulations governing lifestyle, gender roles, politics, and religion. After the elimination of the kapu system, women were allowed to eat formerly forbidden food and to eat with men, the priests no longer offered human sacrifices, and the many prohibitions surrounding the high chiefs were relaxed. Kamehameha II’s mother Keōpūolani played an important role in the elimination of the Hawaiian kapu system, and the move from the ancient religion and traditions. In 1820, when Christian missionaries came to the Hawaiian Islands, Keōpūolani and her second husband Hoapili were among the first of the Hawaiian nobles to convert to Christianity. Keōpūolani then wore Western clothing and learned to read and write. She made a public declaration that the custom of taking multiple spouses by royalty would end and the Christian practice of monogamy would be followed. Kamehameha II never officially converted to Christianity because he refused to give up four of his five wives and his love of alcohol. He was the last Hawaiian king to practice polygamy.

On April 16, 1822, English missionary William Ellis arrived in the Hawaiian Islands with a gift from King George IV of Great Britain, the Prince Regent, a schooner with six guns, to add to the Kingdom of Hawaiian Island’s fleet of ships. Kamehameha II wanted to travel to Great Britain to thank King George IV and to encourage closer diplomatic ties between their two kingdoms. All Kamehameha II’s advisors, including his mother Keōpūolani and his co-regent Kaʻahumanu, were opposed to the trip. After the death of his mother on September 16, 1823, Kamehameha II was determined to travel to Great Britain.

King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu in the Royal Box at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane; Credit – Wikipedia

King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu arrived in Great Britain on May 17, 1824. They were an unusual sight to the British people who had seen few Native Hawaiians or a person as tall as Kamāmalu who was over six feet tall. They toured London, visiting Westminster Abbey but Kamehameha II refused to enter because he did not want to desecrate the British royal burial place “with his presence or his feet stepping in that area.” The royal couple attended the opera and ballet at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London, and a play at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, London.

King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu were scheduled to meet King George IV on June 21, 1824, but the meeting had to be canceled because Queen Kamāmalu became ill. Members of the Hawaiian entourage had caught measles and they had no natural immunity because the people of the Hawaiian Islands had lived in isolation until their contact with Europeans. The Hawaiian entourage was likely exposed to measles on their June 5 visit to the Royal Military Asylum, an orphanage for the children of military parents that was known for its epidemics of childhood diseases. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, epidemics of measles, smallpox, and other diseases threatened to wipe out the entire Native Hawaiian population and disrupted the culture and lives of the islands’ residents.

Twenty-one-year-old Queen Kamāmalu died on July 8, 1824. Her grief-stricken husband King Kamehameha II died six days later on July 14, 1824, at the age of twenty-six. King Kamehameha II lay in state at the Caledonian Hotel in London on July 17, 1824, and large crowds paid their respects. On the following day, the coffins of King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu were placed in the crypt of St Martin-in-the-Fields Church in London, awaiting the voyage back to the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands.

HMS Blonde, the British ship that transported the coffins of King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu back to Hawaii; Credit – Wikipedia

In August 1824, the coffins of King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu left Great Britain on the Royal Navy frigate HMS Blonde under the command of Captain George Anson Byron, 7th Baron Byron. The HMS Blonde arrived in the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands on May 6, 1825.

King Kamehameha II’s brother-in-law William Pitt Kalanimoku, a High Chief who functioned similarly to a prime minister, had been notified of the deaths, and so Hawaiian royalty and nobility gathered at his house where the bodies were moved for the funeral. On May 11, 1825, a state funeral was held for the late King and Queen, the first Christian memorial service for a ruler of Hawaii. The crew from the HMS Blonde participated in the formal procession from the ship to the funeral site, the chaplain of the HMS Blonde said an Anglican prayer, and an American missionary said a prayer in the Hawaiian language.

In the background, the Royal Mausoleum, Mauna ʻAla, now a chapel; Credit – Wikipedia

A Western-style mausoleum was constructed for King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu near the ʻIolani Palace in Honolulu. The mausoleum was a small house made of coral blocks with a thatched roof. King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu were interred there on August 23, 1825. Over time, as more coffins were added, the small vault became crowded. In 1863, construction began on Mauna ʻAla (Fragrant Hills), the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii in Honolulu. On October 30, 1865, the remains of past deceased royals, including King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu, were transferred in a torchlit ceremony at night to the new mausoleum. On November 9, 1887, after the Royal Mausoleum became too crowded, the caskets of the members of the House of Kamehameha were moved to the newly built Kamehameha Tomb, an underground vault, under the Kamehameha Dynasty Tomb. Two additional underground vaults were built over the years. In 1922, the Royal Mausoleum, Mauna ʻAla was converted to a chapel after the last royal remains were moved to tombs constructed on the grounds.

Kamehameha Dynasty Tomb – Royal Mausoleum, Honolulu, Hawai; Credit – By Daderot. – Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1101293

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Flantzer, Susan. (2024). Kamehameha I The Great, King of the Hawaiian Islands. Unofficial Royalty. https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/kamehameha-i-the-great-king-of-the-hawaiian-islands/

- U.S. Department of the Interior. Liholiho (Kamehameha II). National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/puhe/learn/historyculture/kamehameha2.htm

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2024). Kamehameha II. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamehameha_II

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Royal Mausoleum (Mauna ʻAla). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Mausoleum_(Mauna_%CA%BBAla)

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Hawaiian Kingdom. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawaiian_Kingdom