by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

King Charles III and Queen Camilla stand at the top of the steps on the West Terrace before meeting guests attending a Garden Party at Buckingham Palace on May 3, 2023

2024 Garden Parties – May 8, 2024 and May 21, 2024 at Buckingham Palace in London, England and September 5, 2024 at Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Each year two, and sometimes three, garden parties are held at Buckingham Palace in London, England in the late spring or the early summer and one is held at Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, Scotland during Holyrood Week when the Monarch spends a week in the summer visiting various parts in Scotland. About 8,000 guests attend each garden party. The garden parties are a way for the Monarch to recognize and reward public service. A network of sponsors is used to nominate guests including Lord-Lieutenants (the Monarch’s personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom), charities, various societies and associations, government departments, local government, the armed services, the Church of England, and other religions. It is not possible to obtain invitations to garden parties by contacting Buckingham Palace.

BUCKINGHAM PALACE GARDEN PARTY

History

The Garden Party at Buckingham Palace, 28 June 1897 by Laurits Regner Tuxen – Queen Victoria (in the carriage with Alexandra, The Princess of Wales); Credit – Royal Collection Trust

Although previous monarchs held entertainments in the Buckingham Palace garden, the tradition of large, formal, garden parties began during the reign of Queen Victoria when two garden parties were held at Buckingham Palace during her Golden Jubilee in 1887 and her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. King Edward VII, King George V, King Edward VIII, King George VI, and Queen Elizabeth II all held garden parties. Videos of past garden parties can be seen at https://www.britishpathe.com/asset/170525/ King George V’s 1935 garden party is at the top of the page but more video clips can be seen by scrolling down.

Buckingham Palace Garden

Aerial view of Buckingham Palace showing just a part of the garden in the rear (Photo from Queen Elizabeth II’s 90th birthday celebrations); Photo Credit – By Photo:SAC Matthew ‘Gerry’ Gerrard RAF/© MoD Crown Copyright 2016, OGL v1.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91227401

Behind Buckingham Palace and the privacy wall bounded by Constitution Hill to the north, Hyde Park Corner to the west, Grosvenor Place to the south-west, and the Royal Mews, the King’s Gallery, and Buckingham Palace to the south and east, is a 42 acre park, the Buckingham Palace Garden, the setting for monarch’s annual London garden parties. This writer has had the good fortune of visiting Buckingham Palace Garden as it is included with the price of admission to Buckingham Palace. It was truly amazing. I had no idea that such a beautiful park lay hidden behind those walls.

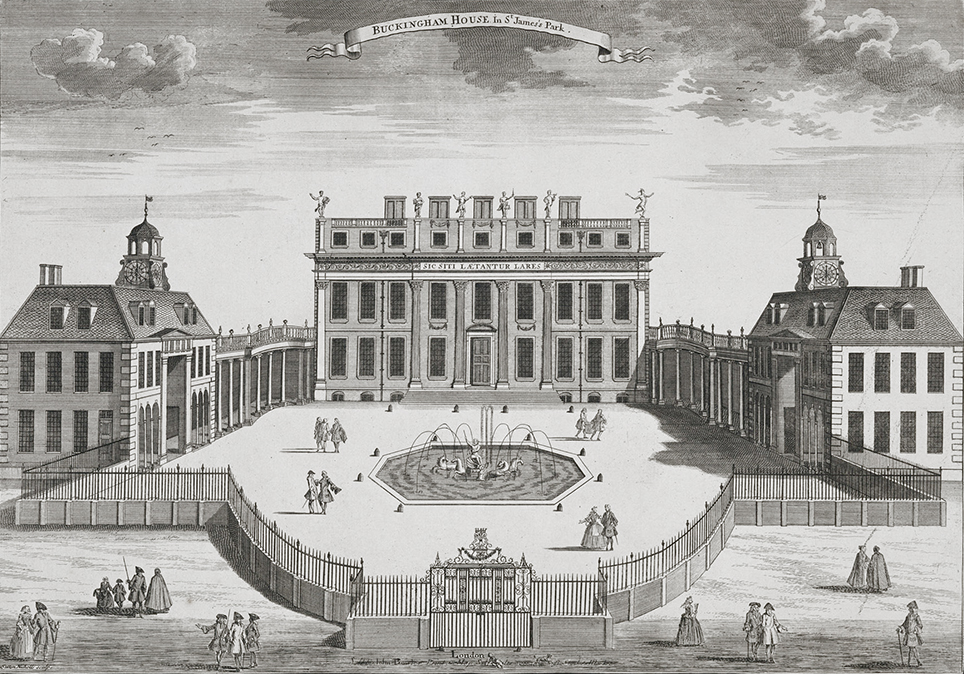

Buckingham House, circa 1710; Credit – Wikipedia

The garden at Buckingham Palace had its beginning from the garden created at Buckingham House, a large townhouse built by John Sheffield, 1st Duke of Buckingham in 1703. The core of today’s Buckingham Palace is Buckingham House. King George III bought Buckingham House in 1761 as a private residence for his wife Queen Charlotte and became known as The Queen’s House. During the 19th century, it was enlarged by architects John Nash and Edward Blore, who constructed three wings around a central courtyard. Buckingham Palace became the official residence of the British monarch during the reign of Queen Victoria.

Western facade (rear) of Buckingham Palace with West Terrace overlooking the Main Lawn. Note the damage to the grass, probably caused by the refreshment marquees from the garden parties. This photo was taken in August after the garden parties.; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

The garden forms a triangle with Buckingham Palace at the top. The western (rear) facade of Buckingham Palace opens to the West Terrace overlooking the Main Lawn. Beyond the Main Lawn is the lake. As stated above, the garden is surrounded by a wall.

The lake; Credit – By KJP1 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=118644180

A view of the lake; Credit – By amandabhslater – https://www.flickr.com/photos/15181848@N02/51368646287/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113624942

Part of the gravel path can be seen in this photo; Credit – By KJP1 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=118644175

A gravel path goes around the garden’s perimeter with paths branching out around the lawns, lake, and flowerbeds. The main trees in the garden are London Plane trees, similar to the American sycamore tree. There are many commemorative trees, planted to celebrate royal occasions, a tradition begun by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The garden is maintained by eight full-time gardeners and several part-time gardeners. Most of the statuary in the garden, including vases and urns on the West Terrace, was designed by architect John Nash.

The Waterloo Vase; Credit – By KJP1 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=118644179

While strolling around the Buckingham Palace Garden, some architectural features can be seen. The Waterloo Vase, a 15-foot (4.6 m) stone urn made from a single piece of Carrara marble, was initially presented to Napoleon I, Emperor of France who intended to have it carved in celebration of his future military victories. After Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, the uncarved vase was given to The Prince Regent, later King George IV. The Prince Regent commissioned sculptor Richard Westmacott to decorate the vase with reliefs celebrating the victory of the British-led force of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Hanover, Brunswick, and Nassau, under the command of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington.

The Summerhouse; Credit – By KJP1 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=118644174

A summerhouse, previously at the old Admiralty Garden at the other end of The Mall, is opposite the Waterloo Vase and is attributed to architect William Kent.

What Happens at a Garden Party?

Guests walking through the gates of Buckingham Palace for a Garden Party on July 23, 1931

The guests, with gentlemen in morning dress or lounge suits and women in day dress, usually with hats or fascinators (national dress and uniform are also often worn), enter the Buckingham Palace gates or the Holyrood Palace gates at 3:00 PM. The guests take tea and sandwiches in marquees erected in the garden.

King Charles III, Queen Camilla, The Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh, and The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester arrive to meet the guests attending the Garden Party at Buckingham Palace, in London, on May 3, 2023

Members of the Royal Family enter the garden at 4:00 PM as the National Anthem is played by one of the two military bands present who also play music throughout the garden party. The Royal Family then walks through the ranks of assembled guests through ‘lanes’, with each Royal Family member taking a different route so that everyone has an equal chance of randomly speaking to a member of the Royal Family. The Royal Family arrives at the Royal Tea Tent, where they meet guests previously selected for the honor. Guests are free to eat, drink, and stroll around the garden.

The Duchess of Edinburgh speaks to guests during the Garden Party at Buckingham Palace on May 3, 2023

HOLYROOD PALACE GARDEN PARTY

Holyrood Palace Garden Party during the reign of King George V

The Holyrood Garden Party began during the reign of King George V (reigned 1910 – 1936). King George V and Queen Mary began the tradition of spending a week each year at Holyrood Palace and hosted the first garden party in the palace gardens in 1928. The guest selection process, the Buckingham Palace garden party program, and the dress requirements are also used for the Holyrood Palace garden party.

King Charles III and Queen Camilla pause for the National Anthem at a Garden Party at the Palace of Holyroodhouse on July 4, 2023

Guests during a garden party at Holyrood Palace on June 29, 2022

The view of Holyrood Palace from Arthur’s Seat, an ancient volcano; Photo Credit – © Howard Flantzer

Holyrood Palace, which this writer has visited, is located at the end of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh and is the British Monarch’s official residence in Scotland. The palace is adjacent to Holyrood Abbey, now in ruins (behind and just to the right of Holyrood Palace in the above photo). The palace, the abbey, and the gardens (the grassy area on the right in the photo above) are set within Holyrood Park. Between 1501 – 1505, James IV, King of Scots constructed a Gothic palace adjacent to the Holyrood Abbey which was the residence of the Scots Monarch. James V, King of Scots added to the palace between 1528 – 1536. From 1671 – 1678, the palace was rebuilt and restored after years of neglect and several fires. However, some of the older palace was retained including the 16th-century historic apartments of Mary, Queen of Scots and the State Apartments.

The Princess Royal greets guests during a Garden Party at Holyrood Palace on July 4, 2023

Holyrood Palace Garden

Behind Holyrood Palace is a ten-acre garden set within the much larger Holyrood Park. Overlooking Holyrood Palace is Arthur’s Seat, an ancient volcano, the main peak of the group of hills in Edinburgh, Scotland, which form most of Holyrood Park. Unlike the Buckingham Palace Garden, the Holyrood Gardens are not walled. It is mostly an open area with panoramic views of Arthur’s Seat and the surrounding hills, and views of the entire park.

The garden we see today was started by Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert. When Queen Victoria and Prince Albert first came to Holyrood Palace, the gardens were overgrown. Prince Albert established new planting areas. Since then, the gardens have been continually improved and updated, and seven greenhouses were built which supply Holyrood Palace with flowers throughout the year. Recent additions to the gardens include a physic garden containing medicinal and culinary plants that would have grown in the 17th-century garden, and a flowering meadow evoking the 15th-century monastic garden of Holyrood Abbey, the first recorded garden on the site.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Garden Parties 2023. The Royal Family. (2023). https://www.royal.uk/news-and-activity/2023-05-03/garden-parties-2023

- Garden Parties. The Royal Family. (n.d.-a). https://www.royal.uk/garden-parties

- Hardman, Robert. (2007). A Year With The Queen. Simon and Schuster.

- Holyrood Week. The Royal Family. (2023). https://www.royal.uk/holyrood-week

- Queen’s Garden Parties. (2019). https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/culture/bazaar-art/g27554967/queen-royal-garden-parties-history/

- Taylor, Elise. (2019). The Historic Evolution of the Royal Family’s Grand Garden Parties. Vogue. https://www.vogue.com/article/the-historic-evolution-of-the-royal-familys-grand-garden-parties

- The Palace of Holyroodhouse Garden. Royal Collection Trust. (n.d.). https://www.rct.uk/visit/palace-of-holyroodhouse/the-palace-of-holyroodhouse-garden

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Buckingham Palace Garden. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buckingham_Palace_Garden#Garden_parties