by Scott Mehl

© Unofficial Royalty 2018

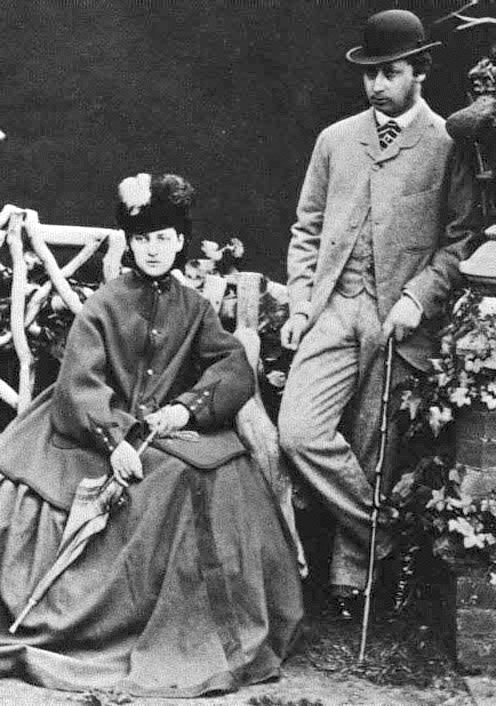

Alexandra and Bertie on their wedding day; Credit – Wikipedia

On March 10, 1863, the future King Edward VII of the United Kingdom married Princess Alexandra of Denmark, at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor. It would be the first royal wedding held at St. George’s Chapel.

Edward’s Early Life

The future King Edward VII of the United Kingdom; Credit – Wikipedia

Prince Albert Edward was born at Buckingham Palace on November 9, 1841, the second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. As the eldest son and heir, he was titled Duke of Cornwall from birth and created Prince of Wales just a month later. Known within the family as Bertie, his education began with a strict program created by his father, but he was not a very good student. He later studied at the University of Edinburgh, Christ Church, Oxford, and Trinity College, Cambridge. Queen Victoria denied his hopes for a military career, however, he held several honorary commissions.

For more about Edward see:

Unofficial Royalty: King Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Alexandra’s Early Life

Alexandra (far right) with her parents and siblings, 1862; Credit – Wikipedia

Alexandra was born December 1, 1844, at the Yellow Palace in Copenhagen, the second child and eldest daughter of the future King Christian IX of Denmark and Princess Luise of Hesse-Kassel. Her siblings were the future King Frederik VIII of Denmark, King George I of the Hellenes, The Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia, The Crown Princess of Hanover, and Prince Valdemar of Denmark. At the time of her birth, she was a Princess of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. However, in 1853, her father was named heir to the Danish throne and Alexandra became a Princess of Denmark. At that time, the family moved to Bernstorff Palace where, despite their royal status, Alexandra and her siblings received a very simple upbringing. Educated privately at home, Alexandra became fluent in English at a young age.

For more about Alexandra see:

Unofficial Royalty: Princess Alexandra of Denmark

The Engagement

Credit – Wikipedia

By 1860, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were already searching for an appropriate bride for the future King. With the help of Bertie’s older sister Vicky – by then the Crown Princess of Prussia – Queen Victoria developed a list of prospective brides. Princess Alexandra of Denmark was fifth on the list, but Vicky found her to be the perfect match for Bertie. And his father agreed that Alexandra was “the only one to be chosen.” The couple first met at Speyer Cathedral in Germany, on September 24, 1861, in a meeting arranged by Vicky. The following year, on September 9, 1862, Bertie and Alexandra became engaged at the Royal Palace of Laeken in Belgium, the home of Bertie’s great-uncle, King Leopold I of the Belgians. Bertie presented Alexandra with a ring featuring six precious stones – purposely selected so that their names would spell out ‘Bertie’ — Beryl, Emerald, Ruby, Turquoise, Jacynth, and Emerald.

The marriage treaty was signed in January 1863 and ratified three months later. It established that the marriage would take place in the United Kingdom, in a Church of England ceremony, and also provided financial arrangements for the future Princess of Wales. Under the terms, she would receive £10,000 annually for her sole use. If she were to become widowed, she would receive £30,000 annually in lieu of any dower. Parliament agreed to the terms of the treaty, granting them a total of £50,000 per year, £10,000 of which was for the bride.

Pre-Wedding Festivities

Princess Alexandra’s arrival procession passing the Mansion House. painting by Robert Dudley; Credit – Wikipedia

Princess Alexandra arrived in England on March 7, 1863, having sailed from Denmark aboard the British Royal yacht Victoria and Albert II. She was greeted upon her arrival in Gravesend, Kent, England by the Prince of Wales, and large crowds who welcomed their future Queen to her new homeland. The couple and the bride’s family traveled by Royal Train to London, where they processed by carriage through the streets of London. Making their way to Paddington Station, they boarded the train to Windsor. Disembarking at Slough, they began another carriage procession to Windsor Castle. Bad weather forced the use of closed carriages, much to the dismay of the vast crowds gathered along the route, hoping to catch a glimpse of Alexandra. Upon their arrival, at 6:30 in the evening, they were greeted by a very anxious Queen Victoria, who had been patiently waiting to welcome her new daughter-in-law and her family.

After a day to rest, the festivities continued on March 9, with numerous delegations being presented to the couple, and presenting wedding gifts, including a necklace and earrings of Golconda diamonds for Alexandra from the Lord Mayor of London, previously approved by the Prince Albert before his death. The couple then rode through Windsor Great Park and were greeted by Eton students including a young Randolph Churchill. That evening, a dinner party was held at Windsor Castle followed by a fireworks display in the Home Park.

Wedding Guests

Although this was the marriage of the future King of the United Kingdom, the guest list was kept rather small, with only a few foreign royals and members of the British aristocracy in attendance. The British Court was still in mourning for Prince Albert, so the ladies’ dresses were limited to grey, lilac, or mauve.

The Groom’s Immediate Family

Queen Victoria

The Crown Prince and Crown Princess of Prussia

Prince Wilhelm of Prussia

Prince and Princess Ludwig of Hesse and by Rhine

Princess Louise

Princess Helena

Prince Arthur

Prince Leopold

Princess Beatrice

The Bride’s Immediate Family

Prince and Princess Christian of Denmark

Prince Frederik of Denmark

Prince Vilhelm of Denmark

Princess Dagmar of Denmark

Princess Thyra of Denmark

Other Royal Guests

The Duke of Cambridge

The Duchess of Cambridge

Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge

King Leopold I of the Belgians

The Count of Flanders

The Duchess of Brabant

Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Ernst Leopold, 4th Prince of Leiningen

Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

Maharajah Duleep Singh

The Duke of Holstein

Prince Friedrich of Hesse-Kassel

Count and Countess Gleichen

Some Other Notable Guests

The Prime Minister, Viscount Palmerston

William Gladstone (future Prime Minister)

Benjamin Disraeli (future Prime Minister)

Charles Dickens

William Makepeace Thackeray

Alfred Tennyson

Charles Kingsley

Jenny Lind

The Wedding Attendants and Supporters

The bridesmaids of Alexandra of Denmark by an unknown photographer. source: National Portrait Gallery, NPG x33255

For the ceremony, the bride was supported by her father, Prince Christian of Denmark, and The Duke of Cambridge. The groom was supported by his brother-in-law, Crown Prince Friedrich of Prussia, and his uncle, Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

In addition, the bride had eight bridesmaids, all of whom were unmarried daughters of British Dukes and Earls:

- Lady Diana Beauclerk, daughter of the Duke of St. Albans

- Lady Elma Bruce, daughter of the Earl of Elgin

- Lady Eleanor Hare, daughter of the Earl of Listowel

- Lady Victoria Howard, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk

- Lady Victoria Montagu Douglas Scott, daughter of the Duke of Buccleuch

- Lady Emily Villiers, daughter of the Earl of Clarendon

- Lady Feodore Wellesley, daughter of the Earl Cowley

- Lady Agenta Yorke, daughter of the Earl of Hardwicke

The Wedding Attire

Credit – Wikipedia

The bride’s dress – a gift from King Leopold I of the Belgians – was made of white silk trimmed with orange blossoms and myrtle and overlaid with flounces of tulle and Honiton lace. The 21-feet long train was of silver moiré also trimmed in orange blossoms. Alexandra’s veil was trimmed with the same lace as her gown, and featured English roses, Irish shamrocks, and Scottish thistles. It was held in place by a wreath of orange blossoms and myrtle atop her head.

Alexandra’s jewels were all wedding gifts. She wore a pearl necklace, earrings, and brooch given to her by The Prince of Wales, an opal and diamond bracelet from Queen Victoria, another opal and diamond bracelet from the Ladies of Manchester, and a diamond bracelet from the Ladies of Leeds.

Alexandra carried a bouquet of orange blossoms, white rosebuds, lily of the valley, orchids, and myrtle. The flowers were held in a “bouquet holder of carved crystal adorned with pearls and coral. The stem features a band of emeralds and diamonds with a jeweled coronet; the foot is formed of a ball of crystal with rubies and diamonds. By turning the ball, the foot springs open into four supports, in each of which is a plume and cipher. Attached to the holder is a chain of gold and pearls and a hoop ring of eight pearls.” The flower and bouquet holder were a gift from the Maharajah Dhuleep Singh. (source: An Historical Record of the Marriage of The Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra of Denmark, published by Darton and Hodge, London)

The groom was resplendent in the full dress uniform of a British General beneath his Garter Robes.

The bridesmaids wore dresses of white glacé silk trimmed with tulle and roses, and wreaths of roses on their heads.

The Ceremony

Wedding at St. George’s Chapel, painting by William Frith, circa 1865; Credit – Wikipedia

Despite her perpetual mourning for the late Prince Consort, Queen Victoria decreed that the Prince of Wales should be married with “the utmost magnificence”. She chose St. George’s Chapel, Windsor as the site of the ceremony. This would be the first of many royal weddings at St. George’s, a tradition that continues to this day for many members of the Royal Family.

Guests began to arrive at the Chapel at 10:30 on the morning of March 10, 1863, and by 11:30 the more prominent attendees were escorted to their seats. The Knights of the Order of the Garter were led in procession by Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister. They were followed by the Lord Chancellor, carrying the Great Seal, and the Lord Chief Justice of all England. Next came the clergy – the Archbishop of Canterbury, followed by the Bishops of London, Oxford, Winchester, and Chester, and the Dean of Windsor. The Diplomatic Corps was the last to take their seats before the royal processions began.

Carriage processions began from Windsor Castle at 11:30, beginning with the royal guests and the bride’s family, followed by members of the British Royal Family, and then the groom and his supporters. The last procession was the bride. The Queen, still in mourning, made her way privately to the chapel, and did not take part in the carriage procession.

Just before noon, Queen Victoria, escorted by the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, made her way to the Catherine of Aragon Closet, a room with an oriel window overlooking the left side of the altar. Dressed in a black silk dress with white collar and cuffs, along with her widow’s cap, she took her seat largely out of view of the guests in the chapel, along with Lady Augusta Bruce – her Lady of the Bedchamber. (She can be seen in the upper right of the picture above)

At 12:00, the procession began, with the royal guests and family members making their way up the aisle, each offering a bow or curtsy to The Queen before taking their seats. Next came The Prince of Wales, accompanied by his brother-in-law and uncle, who processed to The Wedding March. They too stopped to bow to The Queen, who had now stood and come to the front of the balcony to receive their homage. Last to process was the bride, accompanied by her father and the Duke of Cambridge, both in full uniform and decorations. After Alexandra reached the altar and curtseyed to The Queen, the choir sang a chant written by The Prince Consort. Overcome with emotion, The Queen was seen to cry and step back, out of view from those gathered below.

The Archbishop of Canterbury conducted the ceremony. It began with the couple taking their vows, followed by a brief service of readings, prayers, and a homily from the Archbishop. Following the benediction, the couple joined hands, turned to bow and curtsy to The Queen, and began their procession out of the chapel. At this point, The Queen made her way quietly back to the castle.

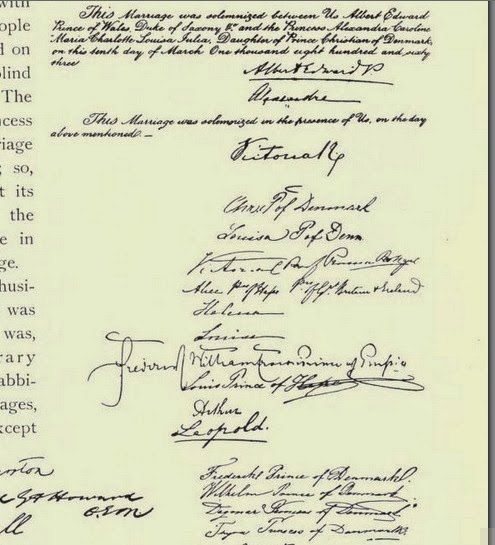

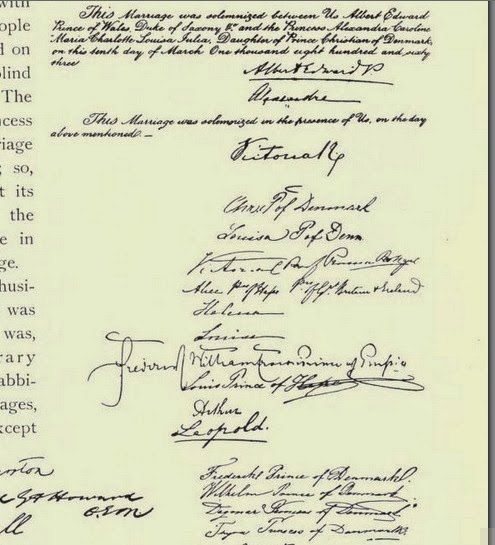

The Witnesses

As is traditional at British royal weddings, many royal guests served as witnesses for the marriage register. These included the groom’s mother, Queen Victoria, the groom’s siblings and their spouses, the bride’s parents and her siblings. Other signers included the Danish Minister, church dignitaries, the Lord Chancellor and other ministers of the Crown.

The Wedding Banquet

Embed from Getty Images

State Dining Room where the royal guests had luncheon

After the wedding, the bride and groom, and their royal guests traveled back to Windsor Castle by carriage. Queen Victoria met Bertie and Alexandra arrived at the Grand Entrance. They made their way to the Green Drawing Room and then the White Drawing Room, where the marriage register was signed. Lunch was then served in the State Dining Room for the royal guests, and in St. George’s Hall for the Diplomatic Corps, members of the royal households, and the more prominent guests at the wedding – nearly 400 people.

There were two wedding cakes, one in each venue. The cake in the State Dining Room was octagonal, featuring a square altar at the center, and a Cupid on each angle holding a piece of wedding cake. The cake in St. George’s Hall weighed nearly 80 pounds. It was octagonal and displayed the arms of the Prince of Wales, the new Princess of Wales, Great Britain and Denmark alternately on each side. It was decorated with orange blossoms and jasmine and surmounted by a vase filled with a jasmine bouquet.

At 4 pm, the newly married couple took leave of their guests and traveled by open carriage, accompanied by a guard of honor from the Coldstream Guards, to Paddington Station where they boarded a train that took them to Osborne House on the Isle of Wight for their honeymoon.

Children

Embed from Getty Images

Bertie and Alexandra had six children:

- Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (1864 – 1892), engaged 1891 to Princess Mary of Teck, died before the wedding

- King George V (1865 – 1936), married 1893 Princess Mary of Teck; had six children, the British Royal Family descends from this marriage

- Princess Louise, Princess Royal (1867 – 1931), married 1889 Alexander Duff, 1st Duke of Fife; had two children

- Princess Victoria (1868 – 1935), unmarried

- Princess Maud (1869 – 1938), married 1896 King Haakon VII of Norway; had one child, the Norwegian Royal Family descends from this marriage

- Prince Alexander John (born and died 1871 – lived only one day)

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.