by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

On February 12, 1554, 16/17-year-old Lady Jane Grey was executed for high treason by beheading at the Tower of London.

Lady Jane Grey, Queen of England

The Streatham Portrait of Lady Jane Grey; Credit – Wikipedia

Lady Jane Grey was born in 1536 or 1537, the eldest of the three daughters of Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk and Lady Frances Brandon. Lady Frances was the granddaughter of the first Tudor king, Henry VII, and the daughter of King Henry VIII’s younger sister Mary Tudor and Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. Frances was the elder of her parents’ two surviving children. Two sons died in childhood, so the only surviving children were Frances and her younger sister Lady Eleanor Brandon who died in 1547.

Lady Jane was very well educated. She studied Greek and Hebrew with John Aylmer, later Bishop of England, and Italian and Latin with Michelangelo Florio, a former Franciscan friar who converted to Protestantism. In 1547, Jane was sent to live in the household of King Edward VI’s uncle, Thomas Seymour, who married King Henry VIII’s sixth wife and widow, Catherine Parr. Jane lived with the couple until the death of Catherine in childbirth in September 1548 and acted as chief mourner at Catherine’s funeral.

The current monarch, King Edward VI, the only son of King Henry VIII, was a minor and a council was to rule until he reached the age of 18. By 1550, John Dudley, Viscount Lisle headed the Privy Council as Lord Protector and was the de facto ruler of England. John Dudley was created Duke of Northumberland in 1551.

The powerful Duke of Northumberland thought marrying one of his sons to Lady Jane Grey would be a good idea. On May 25, 1553, three weddings were celebrated at Durham Place, the Duke of Northumberland’s London home. Lord Guildford Dudley, the fifth surviving son of the Duke of Northumberland married Lady Jane Grey, Guildford’s sister Lady Katherine Dudley married Henry Hastings, Francis Hastings, 2nd Earl of Huntingdon’s heir and Jane’s sister Lady Catherine Grey married Henry Herbert, the heir of William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke.

How did Lady Jane get to be Queen of England?

Embed from Getty Images

‘Lady Jane Grey’s Reluctance to Accept the Crown’, (19th century). Artist: Herbert Bourne

In the early summer of 1553, fifteen-year-old Protestant King Edward VI, King Henry VIII‘s only son, lay dying, probably of tuberculosis. His eldest half-sister Mary (the future Queen Mary I), the Catholic daughter of King Henry VIII’s first wife Catherine of Aragon, was the heir presumptive. The Third Succession Act of 1543 had restored Mary and Edward’s other half-sister Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth I), daughter of King Henry VIII’s second wife Anne Boleyn, to the succession. In addition, the Third Succession Act stipulated that if the children of King Henry VIII did not have heirs, the heirs of his younger sister Mary Tudor should inherit the throne. The heirs of Henry’s elder sister Margaret Tudor who married James IV, King of Scots were excluded presumably to ensure the English throne was not inherited by a Scot. However, in 1603, upon the death of the unmarried and childless Queen Elizabeth I, Margaret Tudor’s great-grandson James VI, King of Scots inherited the English throne and reigned as King James I of England.

As King Edward VI lay dying in the early summer of 1553, the succession to the throne according to the Third Succession Act looked like this, and note that number four in the succession was the Duke of Northumberland’s daughter-in-law.

1) Mary, daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon

2) Elizabeth, daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn

3) Lady Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, daughter of Mary Tudor

4) Lady Jane Grey, daughter of Lady Frances Brandon

5) Lady Catherine Grey, daughter of Lady Frances Brandon

6) Lady Mary Grey, daughter of Lady Frances Brandon

7) Lady Margaret Clifford, daughter of Countess of Cumberland (born Lady Eleanor Brandon, daughter of Mary Tudor)

King Edward VI’s death and the succession of his Catholic half-sister Mary would spell trouble for the English Reformation. Many of Edward’s Council members feared this, including the Duke of Northumberland. What exact role the Duke of Northumberland had in what followed is still debated, but surely he played a big part in the unfolding of the events. King Edward VI opposed Mary’s succession not only for religious reasons but also because of her illegitimacy and his belief in male succession. He also opposed the succession of his half-sister for reasons of illegitimacy and belief in male succession. Both Mary and Elizabeth were still considered to be legally illegitimate.

King Edward composed a document “My devise for the succession” in which he passed over his half-sisters and the Duchess of Suffolk (Frances Brandon). Edward meant for the throne to go to the Duchess’ daughters and their male heirs. The Duke and Duchess of Suffolk were outraged at the Duchess’ removal from the succession, but after a meeting with the ailing king, the Duchess renounced her rights in favor of her daughter Jane. Many contemporary legal experts believed the king could not contravene an Act of Parliament without passing a new one that would have established the altered succession. Therefore, many thought that Jane’s claim to the throne was weak. Apparently, Jane did not have any idea of what was occurring.

After great suffering, fifteen-year-old King Edward VI died on July 6, 1553, most likely from tuberculosis. On July 9, Jane was told that she was Queen, and reluctantly accepted the fact. She was publicly proclaimed Queen with much pomp after Edward’s death was announced on July 10. Queen Jane made a state entry into the Tower of London.

What happened to Jane?

Entry of Queen Mary I with Princess Elizabeth into London in 1553 by John Byam Liston Shaw, 1910; Credit – Wikipedia

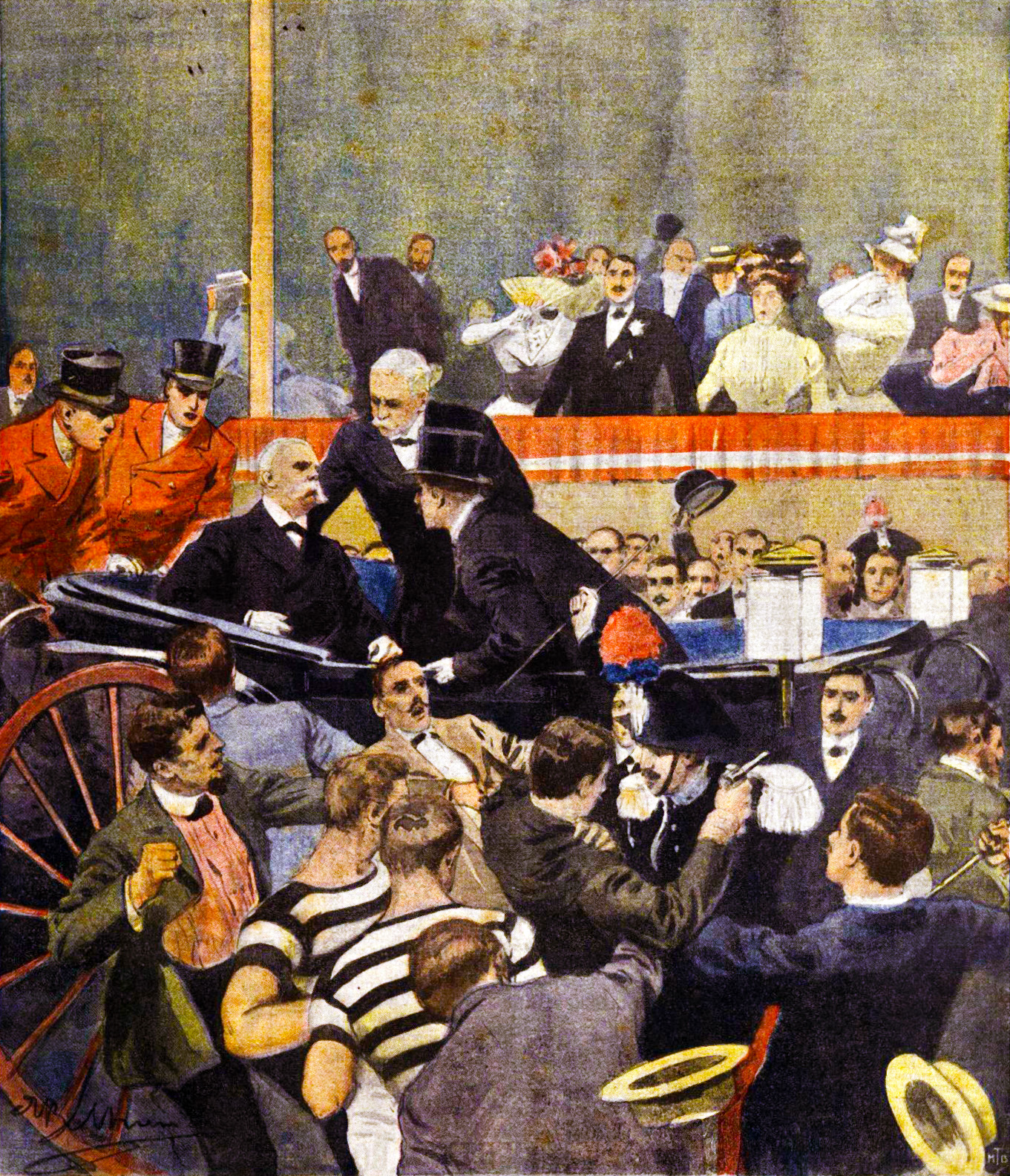

The Duke of Northumberland had to find Mary and hopefully capture her before she could gather support. However, as soon as Mary knew her half-brother was dead, she wrote a letter to the Privy Council with orders for her proclamation as Edward VI’s successor and started to gather support. By July 12, 1553, Mary and her supporters assembled a military force at Framlingham Castle in Suffolk. The Duke of Northumberland set out from London with troops on July 14. The nobility was incensed with Northumberland and the people, for the most part, wanted Mary as their Queen, not Jane. In Northumberland’s absence, the Privy Council switched their allegiance from Jane to Mary and proclaimed her Queen on July 19, 1553. Mary arrived triumphantly into London on August 3, 1553, accompanied by her half-sister Elizabeth and a procession of over 800 nobles and gentlemen.

Jane and Guildford had been in residence at the Tower of London following Jane’s proclamation as Queen. They were separated and remained at the Tower. After a few days, Guildford’s father John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland and Guildford’s four surviving brothers were imprisoned at the Tower of London along with Jane’s father Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk. All the men were eventually attainted and condemned to death. John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland was executed on August 22, 1553.

Jane and her husband were charged with high treason. Their trial took place on November 13, 1553, at Guildhall in London and they were found guilty and sentenced to death. Jane’s sentence was to “be burned alive on Tower Hill or beheaded as the Queen pleases.” Queen Mary appeared as if she was going to be lenient and perhaps pardon Jane but the Protestant rebellion of Thomas Wyatt the Younger in January 1554 sealed Jane’s fate, although she had nothing to do with the rebellion. Wyatt’s Rebellion was a reaction to Queen Mary’s planned marriage to the future King Philip II of Spain.

The Execution

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey by Paul Delaroche, 1833; Credit -Wikipedia

16/17-year-old Lady Jane Grey and her 18/19-year-old husband Lord Guildford Dudley were both beheaded on February 12, 1534. The day before their execution, Guildford asked for a last meeting with his wife but Jane refused saying that it “would only … increase their misery and pain, it was better to put it off … as they would meet shortly elsewhere, and live bound by indissoluble ties.” About ten o’clock on the morning of February 12, 1534, Guildford was led to Tower Hill outside the Tower of London where he was to have a public execution. He gave a brief speech to the assembled crowd, as was customary. Guildford then knelt down, prayed, and asked the people to pray for him. He was killed with a single blow of the ax.

From the window of her room, Jane witnessed a horse and cart bringing Guildford’s body back to the Tower. Jane was then brought out to Tower Green inside the Tower of London where she was to have a private execution. Jane gave a short speech before her execution:

“Good people, I am come hither to die, and by a law I am condemned to the same. The fact, indeed, against the Queen’s highness was unlawful, and the consenting thereunto by me: but touching the procurement and desire thereof by me or on my behalf, I do wash my hands thereof in innocency, before God, and the face of you, good Christian people, this day.”

Jane then recited Psalm 51, a penitential psalm (“Have mercy upon me, O God) in English and handed her gloves and handkerchief to her maid. The executioner asked for her forgiveness, which she granted him, adding, “I pray you dispatch me quickly.” Referring to her head, she asked, “Will you take it off before I lay me down?” The executioner answered, “No, madam.” Jane then blindfolded herself but she failed to find the block with her hands, and cried, “What shall I do? Where is it?” Probably Sir Thomas Brydges, the Deputy Lieutenant of the Tower, helped her find her way. With her head on the block, Jane spoke the last words of Jesus, “Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit!”

Jane and Guildford were buried in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula within the Tower of London where many executed there were buried including the two beheaded wives of Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard.

Memorial in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula at the Tower of London, Credit: www.findagrave.com

Aftermath

The effigy of Lady Frances Brandon on her tomb in Westminster Abbey; Credit – Wikipedia

Jane’s father, Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, was executed on February 23, 1554. The life of his wife Frances was now in ruins. Because her husband was a traitor, all his possessions reverted to the Crown. Frances managed to plead with her first cousin Queen Mary I to show mercy. Mary agreed that some of the Duke of Suffolk’s property could remain with the family. Frances married her Master of the Horse Adrian Stokes in March 1555. They had two stillborn children and a daughter who died in infancy. Frances, aged 42, died on November 20, 1559, at her residence Charterhouse in London with her daughters Catherine and Mary at her bedside. The cost of her funeral was paid by her first cousin Queen Elizabeth I. With her daughter Catherine acting as chief mourner, Frances was buried at Westminster Abbey.

Lord Guildford Dudley’s brothers John, Ambrose, Henry, and Robert Dudley remained imprisoned at the Tower of London in the Beauchamp Tower where they made carvings in the walls. John carved their heraldic devices with his name “IOHN DVDLI” which can still be seen. In 1554, Guildford’s mother Jane Dudley and his brother-in-law Sir Henry Sidney were busy befriending the Spanish nobles around Queen Mary’s new husband, Prince Philip of Spain, hoping they would use their influence to have the Dudley brothers released. In October 1554, John, Ambrose, Henry, and Robert Dudley were released due to their efforts. Robert Dudley, later Earl of Leicester, was the favorite of Queen Elizabeth I from her accession until his death.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Ashley, M. and Lock, J. (1998). The Mammoth Book of British Kings & Queens. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers.

- Dodson, A. (2004). The Royal Tombs of Great Britain. London, p.Gerald Duckworth and Co. Ltd.

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dudley,_1st_Duke_of_Northumberland [Accessed 28 Nov. 2018].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Lady Jane Grey. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Jane_Grey [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan. (2013). Lady Jane Grey, Queen of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/july-10-daily-featured-royal-date/ [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan. (2018). Lord Guildford Dudley. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/lord-guildford-dudley/ [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

- Williamson, D. (1996). Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell.