by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

Prince Platon Alexandrovich Zubov; Credit – Wikipedia

- Patronymics: In Russian, a patronymic is the second name derived from the father’s first name: the suffix -vich means “son of” and the suffixes -eva, -evna, -ova, and -ovna mean “daughter of”.

Prince Platon Alexandrovich Zubov was the last lover of Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia. There was a thirty-eight-year age difference between Platon and Catherine. He was also one of the conspirators in the assassination of Catherine II’s son and successor Paul I, Emperor of All Russia, and was one of the fourteen people present at Paul’s murder. Born on November 26, 1767, Platon was the fifth of the six children and the third of the four sons of Alexander Nikolaievich Zubov (1727 – 1795) and Elizabeth Vasilievna Voronova (1742 – 1813).

Platon Alexandrovich had four older siblings and one younger sibling:

- Anna Alexandrovna Zubova (1760 – after 1787), married Osip Ivanovich Horvath, had two children

- Nicholai Alexandrovich Zubov (1763 – 1805), married Natalia Alexandrovna Suvorov, had seven children

- Dmitri Alexandrovich Zubov (1764 – 1836), married Praskovye Alexandrovna Vyazemskaya, had six children

- Olga Alexandrovna Zubova (1765 – 1849), married Alexander Alexeivich Zherebtsov, had four children

- Valerian Alexandrovich Zubov (1771 – 1804), unmarried

Prince Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin; Credit – Wikipedia

The great love of Empress Catherine’s life was Prince Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin who had a relationship with Catherine from 1774 until he died in 1791. After a period of exclusivity, Potemkin and Catherine worked out a new relationship that preserved their affection toward each other and their political collaborations but allowed each of them to choose other sexual partners. Besides being Catherine’s lover, Potemkin was Grand Admiral of the Black Sea Fleet, Field Marshal of the Russian Army, and Governor-General of New Russia. Potemkin served as a diplomat, was a member of the Imperial Council and was president of the War College. He built the Black Sea Fleet and founded the cities of Sevastopol and Kherson in Crimea. Potemkin’s achievements include the peaceful annexation of Crimea and the successful Russo-Turkish War.

In June 1789, Platon Alexandrovich Zubov was a 22-year-old officer in the Lifeguards Horse Regiment when Count Nikolai Ivanovich Saltykov introduced him to Empress Catherine in an effort to supplant his enemy Prince Grigory Potemkin from his various positions. Potemkin had approved of all Catherine’s other lovers from 1777 – 1789 but he vehemently disapproved of Platon. He saw Platon for what he was – poorly educated, vain, and greedy for wealth, estates, honors and titles for himself, his father and his three brothers. Although Potemkin died in 1791, he was proven correct. Platon would become the last of Catherine’s lovers, become a Count and a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, and along with his father and three brothers who all became Counts, would accumulate enormous fortunes and would become widely reviled for corruption and cruelty.

Platon wearing his honors and a miniature of Catherine; Credit – Wikipedia

Upon Potemkin’s death, Platon succeeded him as the Governor-General of New Russia. In 1795, Count Fyodor Vasilyevich Rostopchin wrote to Count Semyon Romanovich Vorontsov: “Count Zubov is everything here. There is no other will but his. His power is greater than that of Potemkin. He is as reckless and incapable as before, although the Empress keeps repeating that he is the greatest genius the history of Russia has known”.

Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia, 1794; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1796, Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia died at the age of 67 and the 29-year-old Platon went mad with grief. For ten days, he isolated himself in his sister Olga’s home. On the eleventh day, he was visited by Catherine’s son and successor Paul I, Emperor of All Russia who drank to his health. Nevertheless, within a few days, Paul confiscated Platon’s estates, relieved him of all his posts, and strongly advised him to go abroad. Platon traveled for a few years in Poland and various regions of Germany. In 1800, he obtained permission to return to Russia and his confiscated estates were returned to him.

Back in Russia, Platon found dissatisfaction among the nobles with Emperor Paul’s reign. Paul agreed with the practices of autocracy and tried to prevent liberal ideas in the Russian Empire. He did not tolerate freedom of thought or resistance against autocracy. Because he overly taxed the nobility and limited their rights, the Russian nobles, by increasing numbers, were against him. Paul’s reign was becoming increasingly despotic. Eventually, the nobility reached their breaking point.

A conspiracy to assassinate Emperor Paul was organized, some months before it was executed, by Count Peter Ludwig von der Pahlen, Count Nikita Petrovich Panin, and Admiral José de Ribas, with the alleged support of the British ambassador in Saint Petersburg, Charles Whitworth, 1st Earl Whitworth who was the lover of Platon’s sister Olga. Platon was one of the conspirators along with his siblings Nikolai, Olga, and Valerian. The conspirators met and discussed their plans at Olga’s house. The total number of people involved in the conspiracy, according to various estimates, ranges from 180 to 300 people.

The assassination of Emperor Paul I, French engraving, 1880s; Credit – Wikipedia

Platon and his brother Nikolai were among the fourteen people present at Emperor Paul’s assassination. At 1:30 AM on March 23, 1801, a group of twelve men led by Platon’s brother Count Nikolai Alexandrovich Zubov and Levin August von Bennigsen, a German general in the service of the Russian Empire, broke into Paul’s bedroom at the Mikhailovsky Castle in St. Petersburg and found Paul hiding behind some drapes in a corner. The conspirators pulled him out and forced him to a table so he could sign an abdication document. When Paul resisted, Platon’s brother Nikolai struck him with a sword and Platon said to Paul, “You are no longer Emperor. It is Alexander (Paul’s eldest son) who is our master.” Paul finally signed the abdication document after which the assassins strangled and trampled him to death.

Paul’s 23-year-old eldest son Alexander, who probably knew about the coup but not the murder plot, succeeded as Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia. Platon initially played a prominent role and enjoyed influence in Alexander’s early reign. However, Alexander I soon realized that he could not surround himself with those involved in the death of his father without compromising himself and Platon’s days of influence came to an end for good.

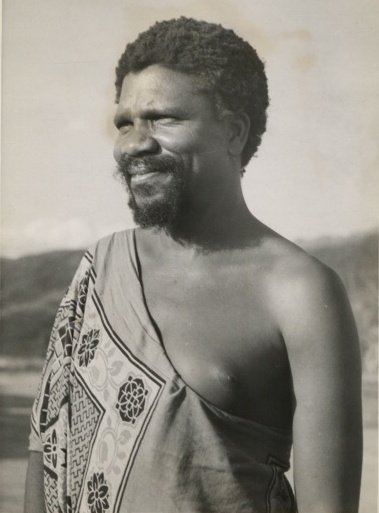

Tekla Ignatyevna Valentinović; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1814, Platon moved to his estates in Lithuania. In 1821, 54-year-old Platon fell madly in love with 19-year-old Tekla Ignatyevna Valentinović (1801-1873), the daughter of a Lithuanian nobleman of modest means. He had seen Tekla with her mother at a horse fair in Vilnius, Lithuania. Through an intermediary, Platon offered Tekla’s family a notable sum of money but his marriage proposal was rejected. Several months later Tekla and her mother arrived at Platon’s estate in Yanishki, Lithuania. Platon made an offer of one million rubles to marry Telka and her mother agreed.

The couple married in 1821 and had a daughter:

- Alexandra Platonovna Zubova (1822 – 1824), died in early childhood

Rundāle Palace; Credit – By Jeroen Komen from Utrecht, Netherlands CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37637993

After the marriage of Platon and Tekla, they made their home at Rundāle Palace, originally built for the Dukes of Courland in what is now Latvia. After the Duchy of Courland was absorbed by the Russian Empire in 1795, Empress Catherine II presented the palace to Platon’s youngest brother Valerian Zubov. Platon inherited Rundāle Palace after the death in 1804 of his unmarried brother.

Platon’s burial site, photographed in the 1860w; Credit – Wikipedia

Prince Platon Alexandrovich Zubov, aged 55, died on April 19, 1822, at Rundāle Palace, three weeks after the birth of his only child. He was buried in the Zubov family crypt at the Coastal Monastery of Saint Sergius in the coastal settlement of Strelna near St. Petersburg, Russia. Platon’s brothers Nikolai and Valerian were also buried in the same crypt. Their burial site was destroyed during the Soviet era.

Platon’s widow Tekla inherited a huge fortune upon his death. However, Platon’s relatives sued due to the lack of a will. The subsequent trial ended in favor of Tekla who made a second marriage in 1826 to Count Andrei Petrovich Shuvalov, who became a prominent figure at the courts of Emperor Nicholas I and Emperor Alexander II. Tekla and her husband had four children and her second marriage brought the vast Zubov estates and fortune into the Shuvalov family.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Platon Zubov. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platon_Zubov> [Accessed 19 July 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2020. Assassination Of Paul I, Emperor Of All Russia (1801). [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/assassination-of-paul-i-emperor-of-all-russia-1801/> [Accessed 19 July 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2018. Catherine II (The Great), Empress Of All Russia. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/empress-catherine-ii-the-great-of-russia/> [Accessed 9 July 2020].

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1981). The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias. New York, NY.: Doubleday

- Massie, Robert, (2016). Catherine the Great. London: Head of Zeus.

- Ru.wikipedia.org. 2020. Валентинович, Текла Игнатьевна. [online] Available at: <https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%92%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87,_%D0%A2%D0%B5%D0%BA%D0%BB%D0%B0_%D0%98%D0%B3%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%82%D1%8C%D0%B5%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%B0> [Accessed 19 July 2020].

- Ru.wikipedia.org. 2020. Зубов, Александр Николаевич (1727). [online] Available at: <https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%97%D1%83%D0%B1%D0%BE%D0%B2,_%D0%90%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%80_%D0%9D%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B5%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87_(1727)> [Accessed 19 July 2020].

- Ru.wikipedia.org. 2020. Зубов, Платон Александрович. [online] Available at: <https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%97%D1%83%D0%B1%D0%BE%D0%B2,_%D0%9F%D0%BB%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%BD_%D0%90%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87> [Accessed 19 July 2020].