by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula; Credit – Von Samuel Taylor Geer – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36712795

The Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula, which this writer has visited, is in the Inner Ward of the Tower of London in London, England. St. Peter ad Vincula is Latin for St. Peter in chains and refers to St. Peter being chained and imprisoned in Jerusalem by King Herod Agrippa. St. Peter ad Vincula is a royal peculiar which means it is under the direct jurisdiction of the monarch. It is also a chapel royal, an establishment in the royal household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign.

The Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula was in existence before the 12th-century and has been demolished and rebuilt a few times. The original chapel was built outside the walls of the Tower of London so that the king could be seen worshiping in public. The king also had a private chapel, the Chapel of St. John the Evangelist within the White Tower in the Tower of London. Eventually, the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula was rebuilt within the walls of the Tower of London and became the place of worship for the inhabitants of the Tower. In 1286, King Edward I, demolished the entire chapel and rebuilt it. Edward I’s chapel was severely damaged by a fire in 1512. The current chapel, built from 1519 – 1520, during the reign of King Henry VIII, replaced the fire-damaged chapel, and it remains a place of worship for the approximately 150 residents who live at the Tower of London.

Credit – https://www.thechapelsroyalhmtoweroflondon.org.uk/welcome/the-chapel-of-st-peter-ad-vincula/

During the 19th-century, there were extensive renovations of the interior of the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. In particular, the floor was badly damaged and had started to collapse because of the number of burials during the 16th-century. Many of the remains that were found were moved to the newly-built crypt. The remains of Anne Boleyn, Lady Jane Grey, and others were identified and markers on the new floor were installed indicating their burial places. In 2014, there were further renovations. New furniture and lighting were installed, the crypt was improved, and office space and facilities were provided for the choir of the Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula.

Buried in the Chapel; Credit – https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/1965/anne-boleyn#view-photo=80722

19th-century marker in the floor identifying the burial place of Anne Boleyn; Credit – Von AloeVera95 – Fotografia scattata personalmente, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48304717

Although there are other burials at the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, it is most associated with the burials of executed people, and visitors cannot help but be reminded of those burials walking over the 19th-century burial markers on the floor and seeing the brass plate listing those “buried in this chapel between” 1534 and 1747 on a chapel wall. Historian Thomas Babington Macaulay wrote of the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula in his 1848 History of England:

“In truth there is no sadder spot on the earth than that little cemetery. Death is there associated, not, as in Westminster Abbey and Saint Paul’s, with genius and virtue, with public veneration and with imperishable renown; not, as in our humblest churches and churchyards, with everything that is most endearing in social and domestic charities; but with whatever is darkest in human nature and in human destiny, with the savage triumph of implacable enemies, with the inconstancy, the ingratitude, the cowardice of friends, with all the miseries of fallen greatness and of blighted fame.”

Site of the scaffold at Tower Hill; Credit – By Bryan MacKinnon – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11456738

The Tower of London had two sites for executions. Tower Hill is outside the walls of the Tower of London, on high ground just north of the Tower of London moat, where public executions of high-profile traitors and criminals were often carried out. Today there is a memorial at the site of the scaffold which can be seen in the photo below.

Credit – By Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10687427

Site of the scaffold on Tower Green; Credit – Wikipedia

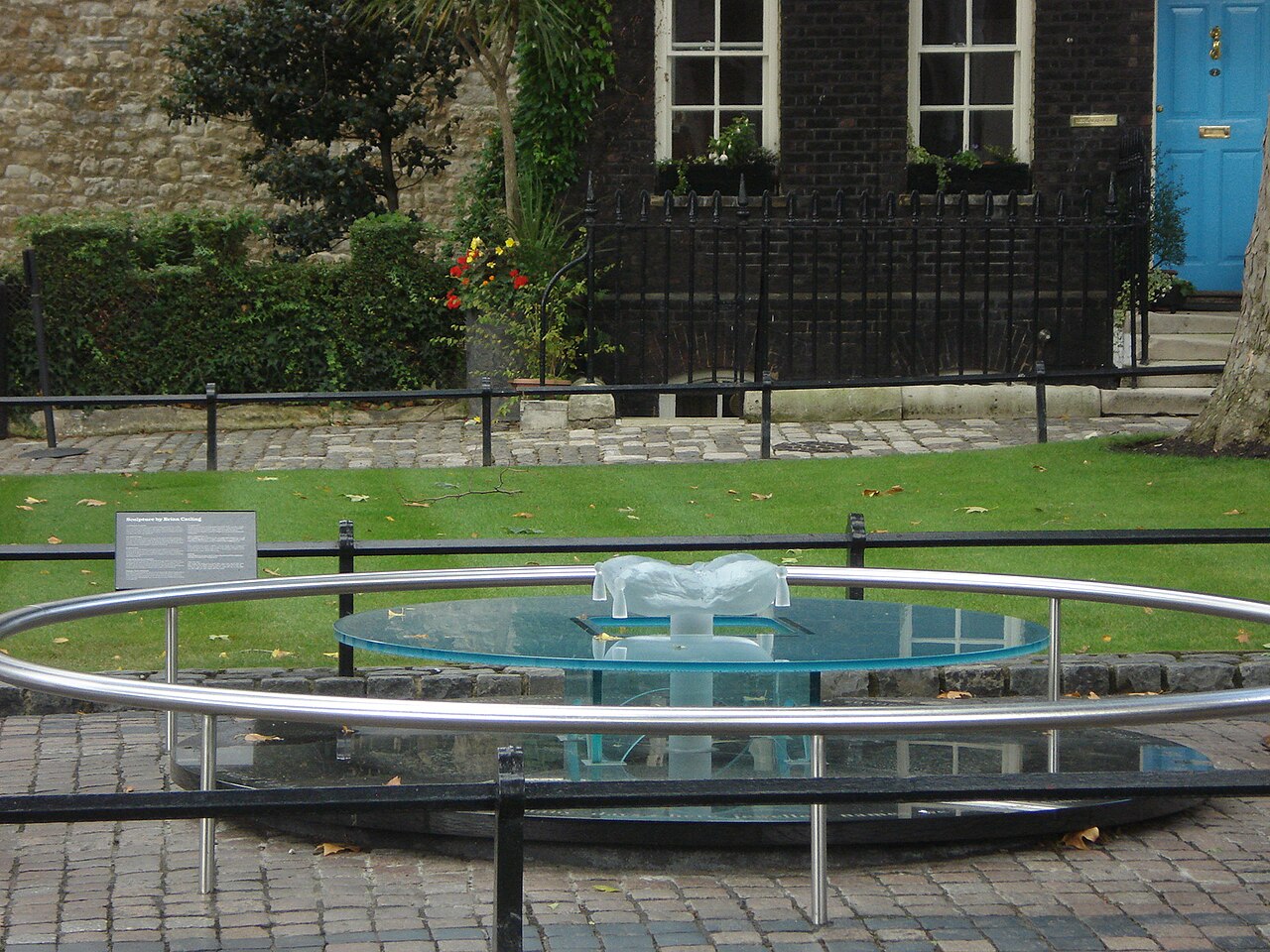

Tower Green is an open space located near the Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula where Anne Boleyn, Catherine Howard, Lady Jane Grey, and several other British nobles were executed as a privilege, to maintain their privacy. In 2006, a new permanent memorial was unveiled on Tower Green to remember all those executed at the Tower of London. Designed by British artist Brian Catling. The memorial has a glass-sculpted pillow at its center. The larger circle of dark stone is engraved with a poem written by the artist and the glass circle is engraved with the names of those executed in front of the Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula on Tower Green.

Those executed either at Tower Hill or Tower Green and buried at the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula:

- Sir Thomas Arundell of Wardour Castle (circa 1502 -February 26, 1552), beheaded on Tower Hill for conspiring to overthrow the government and murder John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, Lord Protector

- Christopher Blount (1556 – March 18, 1601), beheaded on Tower Hill for high treason for participating in the rebellion of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I

- Anne Boleyn (circa 1501- May 19, 1536), second wife of King Henry VIII, beheaded on Tower Green within the Tower of London on charges of adultery, incest, and high treason, some historians think her fall and execution were engineered by Thomas Cromwell

- George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford (1504 – May 17, 1536), brother of Anne Boleyn, beheaded on Tower Hill on charges of incest with his sister and high treason with four other men who were charged with adultery with Anne Boleyn and treason

- Jane Boleyn, Viscountess Rochford (circa 1505 – February 13, 1542), wife of George Boleyn, lady-in-waiting to Queen Catherine Howard, fifth wife of King Henry VIII, beheaded for treason on Tower Green within the Tower of London on charges of treason for arranging meetings between Queen Catherine Howard and her lover Thomas Culpeper

- William Boyd, 4th Earl of Kilmarnock (1705 – August 18, 1746), Scottish peer who joined the 1745 Jacobite Rising, was captured at the Battle of Culloden, beheaded at Tower Hill for treason

- Thomas Cromwell (circa 1485 – July 28, 1540), chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534-1540, beheaded on Tower Hill on charges of treason and heresy

- Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (1565 – February 25, 1601), a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I, beheaded on Tower Green on charges of high treason for an unsuccessful rebellion to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I

- Lord Guildford Dudley (circa 1535 – February 12, 1554), son of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland and husband of Lady Jane Grey, beheaded at Tower Hill on charges of high treason for his probably unwilling participation in his father’s scheme to put his wife Lady Jane Grey on the English throne

- John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504 – August 22, 1553), father of Lord Guildford Dudley and father-in-law of Lady Jane Grey, beheaded on Tower Hill on charges of high treason for his scheme to put his daughter-in-law Lady Jane Grey on the English throne

- Arthur Elphinstone, 6th Lord Balmerino (1688 – 18 August 1746), Scottish peer who joined the 1745 Jacobite Rising, was captured at the Battle of Culloden, beheaded at Tower Hill for treason

- Cardinal John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester (1469 – June 22, 1535), beheaded at Tower Hill by order of Henry VIII during the English Reformation for refusing to accept him as the supreme head of the Church of England, honored as a martyr and saint by the Catholic Church

- Scottish Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat (circa 1667 – April 9, 1747), Scottish peer who joined the 1745 Jacobite Rising, was captured at the Battle of Culloden, beheaded at Tower Hill for treason

- Sir John Gates (1504 – August 22, 1553), beheaded on Tower Hill on charges of high treason for his participation in the scheme to put Lady Jane Grey on the English throne

- Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, 3rd Marquess of Dorset (1517 – February 23, 1554), father of Lady Jane Grey, beheaded at Tower Hill for his participation in the scheme to put his daughter Lady Jane Grey on the English throne

- Lady Jane Grey (circa 1537 – February 12, 1554), the “Nine Days’ Queen”, great-granddaughter of King Henry VII, wife of Lord Guildford Dudley, and daughter-in-law of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, beheaded at Tower Green for her probably unwilling participation in her father-in-law’s scheme to put her on the English throne

- Catherine Howard (circa 1523 – February 13, 1542), fifth wife of King Henry VIII, beheaded for treason at Tower Green on charges of high treason for committing adultery with her distant cousin Thomas Culpeper

- Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk (1536 – June 2, 1572), beheaded at Tower Hill for treason for his participation in the Ridolfi plot with King Philip II of Spain to put Mary, Queen of Scots on the English throne and restore Catholicism in England

- William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford (1614 – December 29, 1680), beheaded at Tower Hill for his participation in the Popish plot which was later discredited, beatified as a Catholic martyr and is known as Blessed William Howard

- Sir Thomas More (1478 – July 6, 1535), lawyer, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist, served Henry VIII as Lord High Chancellor of England from 1529 – 1532, beheaded at Tower Hill by order of Henry VIII during the English Reformation for refusing to accept him as the supreme head of the Church of England, honored as a martyr and saint by the Catholic Church

- Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury (1473 – May 27, 1541), daughter of George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence (brother of King Edward IV and King Richard III), one of the few surviving members of the Plantagenet dynasty after the Wars of the Roses

- James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, 1st Duke of Buccleuch (1649 – July 15, 1685), illegitimate son of King Charles II and his mistress Lucy Walter, beheaded for treason at Tower Hill for the unsuccessful Monmouth Rebellion, an attempt to depose his uncle King James II

- Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (1500 – January 22, 1552), brother King Henry VIII’s third wife Jane Seymour and Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, uncle of King Edward VI and Lord of Protector England from 1547 to 1549, beheaded at Tower Hill on charges of felony after scheming to overthrow the government of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, Lord Protector of England

- Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley (circa 1508 – 20 March 1549) ), brother King Henry VIII’s third wife Jane Seymour and Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, uncle of King Edward VI, second husband of King Henry VIII’s sixth wife and widow Catherine Parr, beheaded on Tower Hill on charges of treason for a failed plot against his brother Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

- Sir Ralph Vane (? – February 26, 1552), hanged at Tower Hill for conspiring to overthrow the government and murder John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, Lord Protector of England

Works Cited

- Borman, Tracy, 2015. The Story of The Tower of London. London: Merrell Publishers Limited and Historical Royal Palaces.

- Chapels Royal, H., 2021. Chapels Royal, H M Tower of London | The Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. [online] Thechapelsroyalhmtoweroflondon.org.uk. Available at: <https://www.thechapelsroyalhmtoweroflondon.org.uk/welcome/the-chapel-of-st-peter-ad-vincula/> [Accessed 10 March 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Church of St Peter ad Vincula. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_St_Peter_ad_Vincula> [Accessed 10 March 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Tower Hill. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tower_Hill#Executions> [Accessed 10 March 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Tower of London. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tower_of_London> [Accessed 26 February 2021].

- Findagrave.com. 2021. Memorials in Chapel of Saint Peter-ad-Vincula – Find A Grave. [online] Available at: <https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/658439/memorial-search?page=4#sr-173777848> [Accessed 10 March 2021].

- Thurley, Simon, Impey, Edward and Hammond, Peter, 2005. The Tower of London – The Official Guidebook. London: Historical Royal Palaces.