by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2017

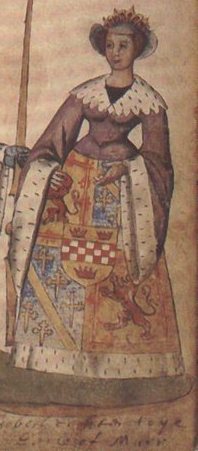

Robert II, King of Scots from Forman Armorial (produced for Mary, Queen of Scots); Credit – Wikipedia

The first monarch of the House of Stewart, Robert II, King of Scots, was born at Paisley Abbey on March 2, 1316. He was the only child of Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland and Marjorie Bruce, the daughter of Robert I the Bruce, King of Scots. His 19-year-old mother Marjorie had been riding in Paisley, Renfrewshire Scotland. Her horse was suddenly startled and threw her to the ground. Marjorie went into premature labor and her child Robert was delivered by caesarean section at the nearby Paisley Abbey. Sadly, Marjorie died within a few hours.

Robert’s father Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland gave his name to the Royal House of Stewart (later Stuart). The surname Stewart comes from the word steward, which means one who organizes the house of a king. The title of High Steward or Great Steward was given in the 12th century to Walter FitzAlan and shortly afterward, it was made a hereditary title. Walter FitzAlan’s grandson started to use Stewart as his surname. In 1371, Robert II, the 7th, and the last High Steward inherited the throne of Scotland. Since that time, the title of High (or Great) Steward of Scotland has been held as a subsidiary title of Duke of Rothesay and Baron of Renfrew, among the titles traditionally held by the heir apparent of Scotland. When James VI, King of Scots succeeded to the English throne upon the death of Queen Elizabeth I, those titles for the heir apparent came with James. Even today, The Prince of Wales holds the titles traditionally held by the English heir apparent, but also the traditional titles of the Scottish heir apparent: Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew, Lord of the Isles, Prince and Great Steward of Scotland.

Robert had three half-siblings from his father’s second marriage to Isabel de Graham, daughter of Sir Nicholas de Graham, Lord of Dalkeith and Abercorn and Mary of Strathearn

- Sir John Stewart of Ralston, married Alicia Mure, had issue

- Sir Andrew Stewart, no issue

- Egidia Stewart, married (1) Sir James Lindsay, of Crawford, Lord of Crawford and Kirkmichael, had issue (2) Sir Hugh Eglinton, Laird of Aird Rosainb, Eglintoun and Ormdale (3) Sir James Douglas of Dalkeith

In 1318, two-year-old Robert was declared heir to the Scottish throne if his grandfather Robert I did not have any male issue. Six years later, Robert I and his second wife Elizabeth de Burgh had a son David, who became heir to the Scottish throne. Robert’s father Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland, died on April 9, 1326. He was buried at Paisley Abbey, alongside his first wife, Marjorie Bruce, and the previous five High Stewards. Ten-year-old Robert became the 7th High Steward of Scotland. The orphaned Robert was placed under the guardianship of his paternal uncle Sir James Stewart of Durrisdeer, who raised his nephew and served as his tutor.

On June 7, 1329, Robert’s grandfather Robert I the Bruce, King of Scots died at the age of 54 and was succeeded by his five-year-old son David II, King of Scots. Robert I’s funeral procession was led by a line of knights dressed in black, including Robert’s 13-year-old grandson Robert Stewart, 7th High Steward of Scotland, the future Robert II, King of Scots, the son of his daughter Marjorie Bruce. In 1326, the Scottish Parliament had restored Robert Stewart to the line of succession in the event his uncle David, who was eight years younger, did not have any male heirs. At the time of his restoration to the succession, Robert received grants of land in Argyll, Roxburghshire, and the Lothians.

However, David II’s accession to the throne sparked another war, the Second War of Scottish Independence, and Robert’s position as heir was threatened. The death of Robert I had weakened Scotland considerably and his successor David II was still a child. The year before he had died, Robert I had arranged for the marriage of his four-year-old David to the seven-year-old Joan of the Tower, youngest daughter of King Edward II of England, in hopes of strengthening relations with England.

However, in 1332-1333, David’s brother-in-law, King Edward III of England, invaded Scotland in support of Edward Balliol‘s claim to the Scots throne and defeated the Scots. Edward Balliol was the eldest son of John Balliol who had been King of Scots from 1292 – 1296. David and Joan sought refuge in France and remained there from 1334 until May of 1341 when David returned to Scotland and took control of the government. King Philippe VI of France persuaded David to invade England. However, the Scots forces were defeated at the Battle of Neville’s Cross on October 17, 1346, and David was taken prisoner. He was held by the English for 11 years and was finally freed in 1357 by the Treaty of Berwick which stipulated that a large ransom would be paid over the next 10 years. Robert Stewart played a major role in the Bruce resistance to Edward Balliol and acted as Guardian of the Kingdom (regent) during David II’s years in France and his imprisonment in England.

Battle of Neville’s Cross from a manuscript Froissart’s Chronicle; Credit – Wikipedia

Robert had two wives. Elizabeth Mure died before Robert became king and Euphemia de Ross was his only Queen Consort. At first, Elizabeth Mure was the mistress of Robert Stewart. The couple married in 1346, but the marriage was not in agreement with the Canon Law of the Roman Catholic Church. After receiving a papal dispensation, the couple remarried. The children born before their marriage were legitimized. Despite the legitimization of Elizabeth’s children, there were family disputes over her children’s right to the crown.

Elizabeth and Robert’s daughter Jean Stewart and her second husband Sir John Lyon, Lord of Glamis had one son Sir John Lyon. Through him, Jean, and therefore Elizabeth Mure and Robert II, are ancestors of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, formerly Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. The elder Sir John was a courtier and diplomat, and was appointed Keeper of the Privy Seal upon the accession of Robert II in 1371. The following year, Robert II granted him “the free barony of Glamuyss in the sheriffdom of Forfar.” Glamis has remained the seat of the family ever since. See Wikipedia: Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne for more information.

Elizabeth and Robert had at least ten children:

-

-

- Robert III, King of Scots; born John Stewart, Earl of Carrick (c.1337/40 – 1406), married Anabella Drummond, had issue

- Walter Stewart, Lord of Fife (c.1338–1362), married Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Fife, no issue

- Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany (c. 1340 – 1420), married (1) Margaret Graham, Countess of Menteith, had issue (2) Muriella Keith, had issue

- Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan (1343 – 1405), married Euphemia I, Countess of Ross, no issue

- Margaret Stewart, married John of Islay, Lord of the Isles, had issue

- Marjorie Stewart, married (1) John Dunbar, Earl of Moray (2) Sir Alexander Keith

- Jean Stewart, married (1) Sir John Keith, (2) Sir John Lyon, Lord of Glamis, had one son (3) Sir James Sandilands

- Isabella Stewart, married (1) James Douglas, 2nd Earl of Douglas, no issue (2) David Edmonstone

- Katherine Stewart, married Sir Robert Logan of Grugar and Restalrig, Lord High Admiral of Scotland

- Elizabeth Stewart, married Sir Thomas Hay, Lord High Constable of Scotland

-

Elizabeth Mure died before May 1355 and was buried at Paisley Abbey in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland.

Robert II, King of Scots and Euphemia, Queen of Scots from Forman Armorial (produced for Mary, Queen of Scots); Credit – Wikipedia

Euphemia de Ross was the daughter and probably the only child of Hugh, 4th Earl of Ross and his second wife Margaret de Graham, daughter of Sir David de Graham of Montrose. On May 2, 1355, Euphemia married Robert Stewart, 7th High Steward of Scotland. In 1357, Robert was granted the title Earl of Strathearn, so Euphemia was then the Countess of Strathearn.

Euphemia and Robert had four children. The children of Robert II from both his marriages considered themselves the rightful heirs to the throne of Scotland, causing considerable family conflict.

- David Stewart, Earl of Strathearn (1357 – circa 1386), married a sister of David Lindsay, 1st Earl of Crawford, whose first name is unknown, had one child Euphemia Stewart, Countess of Strathearn

- Walter Stewart, Earl of Atholl (circa 1360 – 1437), married Margaret Barclay, Lady of Brechin, had issue, beheaded for his involvement in the assassination of James I, King of Scots

- Elizabeth Stewart, married David Lindsay, 1st Earl of Crawford, had issue

- Egidia Stewart, married William Douglas of Nithsdale, had issue

Euphemia Stewart, Countess of Strathearn, granddaughter of Euphemia and Robert through their son David Stewart, Earl of Strathearn, is an ancestor of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother formerly Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. As an only child, Euphemia Stewart was heir to her father’s earldoms. She married Patrick Graham and their daughter Elizabeth married Sir John Lyon, 1st Master of Glamis, the son of Sir John Lyon who had married Jean Stewart, daughter of Robert II and Elizabeth Mure (see above). See Wikipedia: Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne for more information.

In the later years of his reign, David II, King of Scots continued to pursue peace with England and worked to make Scotland a stronger kingdom with a more prosperous economy. David II, aged 46, died unexpectedly on February 22, 1371, at Edinburgh Castle and was buried at Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh, now in ruins. As both his marriages were childless, David was succeeded by his nephew, his senior by eight years, the son of his half-sister Marjorie, who became Robert II, King of Scots, the first monarch of the House of Stewart.

Robert II, King of Scots was crowned at Scone on March 26, 1371, by William de Landallis, Bishop of St. Andrews. Immediately after his coronation, his eldest son John, Earl of Carrick, was recognized as the heir apparent. In order to dispel all conflict among the children of his two marriages, Robert II had a succession act passed in Parliament in 1373. If the heir apparent John, Earl of Carrick dies without sons, the succession would pass to Robert, Duke of Albany and then to his younger brothers from Robert II’s two marriages in order of birth. As his reign progressed, Robert II delegated more power to his three eldest sons, John, Earl of Carrick and heir to the throne; Robert, Duke of Albany and Alexander, Earl of Buchan, who became his lieutenant in the north of Scotland.

Dundonald Castle; Photo Credit – By Otter – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4506227

Fortunately, Robert II’s reign was more peaceful than previous reigns. Hostilities with England were renewed in 1378 and continued intermittently for the rest of Robert II’s reign. In 1384, when Robert II became senile, he left the administration of the kingdom to his eldest son John, Earl of Carrick. Euphemia de Ross, Queen of Scots died in 1386 and was buried at Paisley Abbey in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland. Robert II, King of Scots survived his wife by four years, dying on April 19, 1390, at the age of 74 at Dundonald Castle in Ayrshire. He was buried at Scone Abbey. His son John, Earl of Carrick succeeded him as Robert III, King of Scots.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- “David II, King Of Scots”. Unofficial Royalty. N.p., 2017. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- “High Steward Of Scotland”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- “Robert I Of Scotland”. Unofficial Royalty. N.p., 2017. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- “Robert II Of Scotland”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- “Walter Stewart, 6Th High Steward Of Scotland : Genealogics”. Genealogics.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- “Walter Stewart, 6Th High Steward Of Scotland”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

- Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell, 1996. Print.

- “Wives of Robert II: Elizabeth Mure and Euphemia de Ross”. Unofficial Royalty. N.p., 2017. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.