by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2025

History

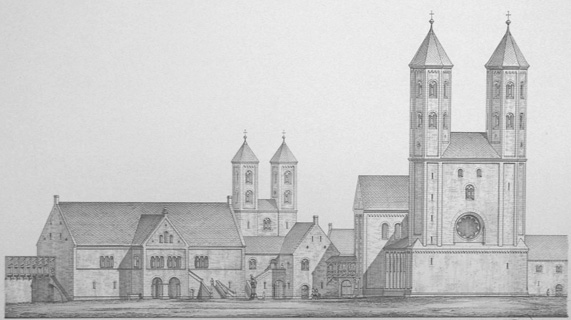

Chapel of Grace in Altötting, Bavaria, Germany; Credit – Wikipedia

The Chapel of Grace (Gnadenkapelle in German), also known as the Holy Chapel (Heilige Kapelle in German), is in Altötting, Bavaria, Germany. The original chapel dates from the 8th to 10th centuries and was expanded in the Gothic style in the 15th century. For 500 years, Roman Catholics have been making pilgrimages to Altötting in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary, including Pope Pius VI in 1782, Pope Saint John Paul II in 1980, and Pope Benedict XVI in 2006. It is a Bavarian national shrine and one of the most important and most visited pilgrimage destinations in Germany and Europe.

The wooden image of the Blessed Virgin Mary at the Chapel of Grace; Credit – By S. Finner: Siddhartha Finner, Dipl.Ing.-Architektur

Since the 14th century, the Chapel of Grace has housed an image made from linden wood of a standing Blessed Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus. The statue has been dressed in fabric from the wedding dresses of Bavarian princesses since 1518. The scepter and crown were donated by Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria. In 2006, when Pope Benedict XVI made a pilgrimage to Altötting, he laid his bishop’s ring, which he had worn until he was elected Pope, before the wooden image of Mary. The ring is now attached to the scepter on the statue. The Chapel of Grace became a popular pilgrim destination because of the miraculous recovery in 1489 of a drowned young boy after his mother laid his body before the wooden image and prayed to the Blessed Virgin Mary for a miracle.

What is a separate burial?

A separate burial is a form of partial burial in which internal organs are buried separately from the rest of the body. Separate burials of the heart and viscera (the intestines) were common among the higher ranks of European society. Removing the organs was part of normal embalming practices. When a person died too far from home to make a full body burial at home feasible, it was often more convenient for the heart or entrails to be carried home as representations of the deceased.

Eventually, in some royal families, separate burials became the usual practice. In addition to the separate burials of the House of Wittelsbach, the ruling family of Bavaria, the House of Habsburg, the ruling family of Austria, is also known for separate burials. It became traditional for the body to be interred in the Imperial Crypt in the Capuchin Church in Vienna, the heart to be placed in an urn in the Herzgruft, the Heart Crypt in the Loreto Chapel of the Augustinerkirche in Vienna, and the entrails to be placed in an urn in the Ducal Crypt of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna.

Heart Burials at the Chapel of Grace

Heart urn of Karl VII, Holy Roman Emperor, Elector of Bavaria in the Chapel of Grace; Credit – Wikipedia – Von Ricardalovesmonuments – File: Gnadenkapelle (Altötting)

The Bavarian rulers of the Wittelsbach dynasty practiced separate burials as early as the late 1500s. When Georg (the Rich), Duke of Bavaria-Landshut died in 1503, his viscera were interred at the Church of Our Lady in Ingolstadt, and his body was interred in the Wittelsbach crypt in Landshut, Bavaria. Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, who died in Ingolstadt in 1651, began the Bavarian tradition of separate burial. His remains were divided into three parts and buried in three different places in Bavaria: his viscera were buried at the Church of Our Lady in Ingolstadt, his body was buried at St. Michael’s Church in Munich, and his heart was buried at the Chapel of Grace in Altötting, which established the Wittelsbach tradition of burying the hearts of family members there.

Below is a list of the heart urns placed in niches. These heart urns are visible and are made from silver, with some gilded and decorated with precious stones.

- Marie Anne Henriëtte Leopoldine de La Tour d’Auvergne, Countess Palatine of Sulzbach (1708 – 1728), mother of Karl Theodor, Elector of Bavaria

- Karl VII, Holy Roman Emperor, Elector of Bavaria (1697 – 1745), double urn with his wife Maria Amalie

- Maria Amalie of Austria, Holy Roman Empress, Electress of Bavaria (1701 – 1756), double urn with her husband

- Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria (1727 – 1777)

- Maria Franziska of Sulzbach, Countess Palatine of Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld (1724 – 1794), mother of Maximilian I Jospeh, King of Bavaria

- Karl Theodor, Elector of Bavaria (1724 – 1799)

- Maximilian I Joseph, Elector of Bavaria, King of Bavaria (1756 – 1825)

- Maximilian II, King of Bavaria (1811 – 1864)

- Ludwig I, King of Bavaria, abdicated (1786 – 1868)

- Ludwig II, King of Bavaria (1845 – 1886)

- Marie of Prussia, Queen of Bavaria (1825 – 1889), wife of Maximilian II, King of Bavaria

- Otto, King of Bavaria, deposed (1848 – 1916)

- Maria Theresia of Austria-Este, Queen of Bavaria (1849 – 1919), wife of Ludwig III, King of Bavaria

- Ludwig III, last King of Bavaria (1845 – 1921)

- Antonia of Luxembourg, Crown Princess of Bavaria (1899 – 1954), 2nd wife of Crown Prince Rupprecht

- Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria (1869 – 1955), son of Ludwig III, King of Bavaria

Below is a list of heart urns that are not visible because they are embedded in the wall or buried beneath the paved floor.

- Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly (1559 – 1632), Field Marshal who commanded the Catholic League’s forces in the Thirty Years’ War

- Elisabeth of Lorraine, Electress of Bavaria (1574 – 1635), first wife of Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, her entrails are also interred in the Chapel of Grace

- Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria (1573 – 1651)

- Cardinal Franz Wilhelm of Bavaria, Count of Wartenberg, Prince-Bishop of Regensburg (1593 – 1661), son of Prince Ferdinand of Bavaria, grandson of Albrecht V, Duke of Bavaria

- Albrecht Sigismund of Bavaria, Prince-Bishop of Freising and Regensburg (link in German) (1623 – 1685), son of Albrecht VI, Duke of Bavaria

- Maria Violante of Sternberg (1697 – 1700), drowned with her father Johann Josef, Count of Sternberg and her mother, born Countess Marie Violanta Terezie von Preysing, while crossing the Inn River in Passau on their way home from a pilgrimage to the Chapel of Grace.

- Joseph Clemens of Bavaria, Archbishop-Elector of Cologne (1671 – 1723), son of Ferdinand Maria, Elector of Bavaria

- Clemens August of Bavaria, Archbishop and Elector of Cologne (1700 – 1761), son of Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria

- Cardinal Johann Theodor of Bavaria, Prince-Bishop of Regensburg (1703 – 1763), son of Maximilian II Emanuel, Prince-Elector of Bavaria

- Clemens Franz Paul, Prince of Bavaria (1722–1770), son of the Imperial Field Marshal, Ferdinand of Bavaria and the grandson of Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria

- Maria Anna Josepha of Bavaria, Margravine of Baden-Baden (1734 – 1776), daughter of Karl Albrecht, Elector of Bavaria, later Karl VII, Holy Roman Emperor, wife of Ludwig Georg, Margrave of Baden-Baden

- Maria Anna of Palatinate-Sulzbach, Duchess of Bavaria (1722 – 1790), wife of Clemens Franz Paul, Prince of Bavaria

- Maria Anna Sophie of Saxony, Electress of Bavaria (1728 – 1797), wife of Maximilian III, Elector of Bavaria

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2004). Böhmisches Adelsgeschlecht. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sternberg_(b%C3%B6hmisches_Adelsgeschlecht)

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2012). Form der Teilbestattung, bei der die Bestattung der inneren Organe getrennt vom übrigen Körper erfolgt. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Getrennte_Bestattung

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2007). Wallfahrtskapelle in Altötting. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnadenkapelle_(Alt%C3%B6tting)

- Gnadenort Altötting | Bistum Passau. (2025). Gnadenort Altötting; bistum-passau. https://www.gnadenort-altoetting.de/

- Herzbestattungen. (2025). Gnadenort Altötting; bistum-passau. https://www.gnadenort-altoetting.de/geschichte-institutionen/geschichte-von-altoetting/herzbestattungen

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2025). Altötting. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation.

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2024). Heart-burial. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation.

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2025). Shrine of Our Lady of Altötting. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation.