by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

Credit – Wikipedia

Mary Boleyn was the elder sister of Anne Boleyn, Queen of England, King Henry VIII’s ill-fated, second wife. The date and place of Mary’s birth are uncertain. She was born sometime between 1499-1500, either at Blickling Hall in Norfolk, England or Hever Castle in Kent, England. Anne’s father was Thomas Boleyn (later 1st Earl of Wiltshire, 1st Earl of Ormond, 1st Viscount Rochford), a diplomat for King Henry VII and King Henry VIII. He was descended from Eustace II, Count of Boulogne who fought for William the Conqueror during the Battle of Hastings. “Boulogne” eventually was anglicized to “Boleyn.” Mary’s mother was Lady Elizabeth Howard, the eldest daughter of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk. Elizabeth’s eldest brother was Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, a prominent Tudor politician, and one of her other brothers was Lord Edmund Howard, the father of Catherine Howard, King Henry VIII’s fifth wife. Through her mother, Mary was a descendant of King Edward I of England.

Mary had four siblings but only two survived childhood:

- Anne Boleyn, Queen of England (circa 1501-1507 – 1536), married King Henry VIII of England, had one surviving child, Queen Elizabeth I of England

- George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford (c. 1504 – 1536), married Jane Parker, no children; George was executed as one of his sister Anne’s supposed lovers and his wife Jane was executed with Henry VIII’s fifth wife Catherine Howard

Hever Castle where Mary grew up with her siblings; Credit – Wikipedia

Mary was most likely educated with her brother George and her sister Anne at Hever Castle in Kent. In 1514, when Mary Tudor, King Henry VIII’s 18-year-old younger sister, left for France to become the third wife of the 52-year-old King Louis XII of France, Mary Boleyn accompanied her as a maid-of-honor. Within a few weeks, most of Mary Tudor’s English ladies were ordered to return home. However, Mary Boleyn was allowed to stay most likely due to her father’s diplomatic influence.

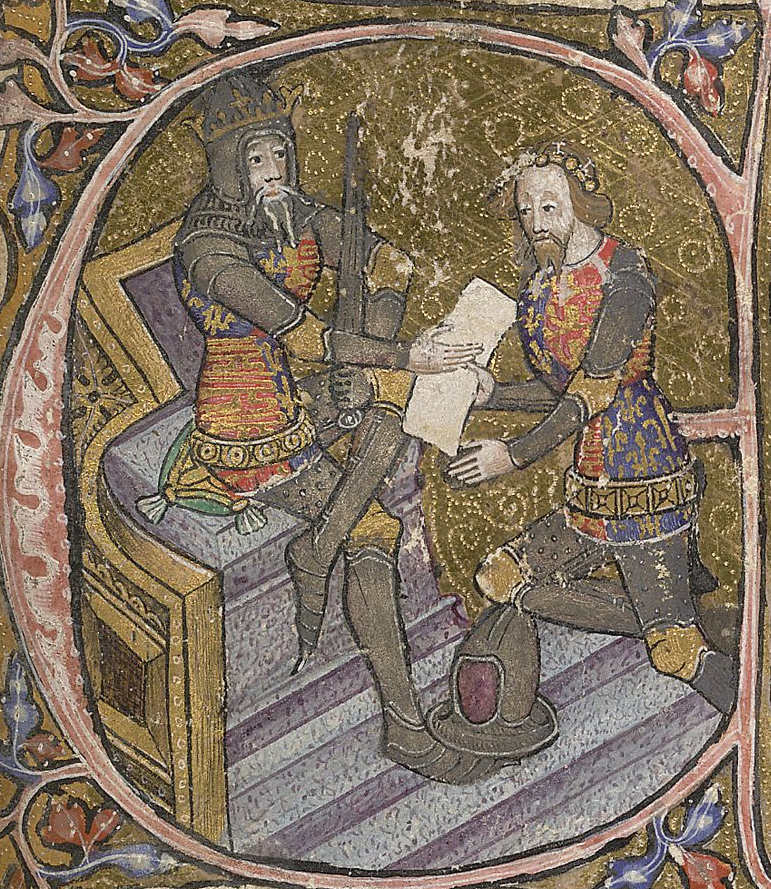

King François I of France; Credit – Wikipedia

King Louis XII of France died on January 1, 1515, just three months after his wedding to Mary Tudor. As he had no son, he was succeeded by the next in line of succession, his son-in-law François d’Angoulême from the House of Valois-Angoulême as King François I of France. Shortly after King Louis XII’s death, Mary Tudor secretly married Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, the best friend of Mary Tudor’s brother King Henry VIII. When Mary Tudor and Brandon returned to England to face the wrath of her brother, Thomas Boleyn removed his daughter Mary from the service of Mary Tudor and placed her in the household of Claude of France, Duchess of Brittany, Queen of France, the wife of the new king, François I. During Mary’s time at the French court, there were rumors that she was having an affair with King François I. Some historians believe the rumors were exaggerated, however, there is documentation that François referred to Mary as “the English mare” and “a very great whore, the most infamous of all.”

Sir William Carey, Mary’s first husband; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1519, Mary was sent back to England where her father arranged for her to be a maid-of-honor to Catherine of Aragon, King Henry VIII’s first wife. On February 4, 1520, in the Chapel Royal at Greenwich Palace, Mary married Sir William Carey (circa 1500 – 1528), who served King Henry VIII as a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber. King Henry VIII attended the wedding ceremony and gave the couple a monetary gift.

King Henry VIII of England in 1520; Credit – Wikipedia

At some point, perhaps even before her marriage, Mary became Henry VIII’s mistress, supplanting Elizabeth Blount, but the starting date and length of the relationship are unknown. Wiliam Carey profited from his wife’s affair as he was granted manors and estates by King Henry VIII. Two children were born during the marriage of Mary and William. Because of Mary’s affair with King Henry VIII, it has been suggested that one or both of the children may have been Henry VIII’s biological children and although there is no proof, this claim has been the continued subject of debate. On June 22, 1528, at the age of 28, William Carey died of the sweating sickness. By the time of William’s death, Mary’s sister Anne had already caught the attention of King Henry VIII.

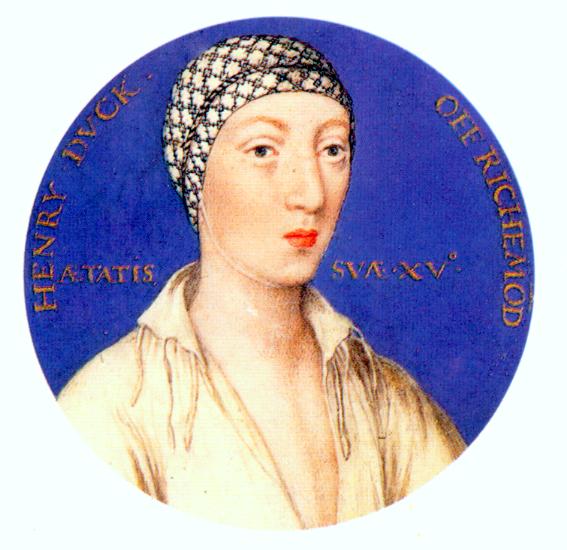

Mary’s daughter Catherine Carey, circa 1562; Credit – Wikipedia

Mary’s son, Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, circa 1561-1563; Credit – Wikipedia

Children born during the marriage of Mary Boleyn and William Carey:

- Catherine Carey (1524 – 1569), married Sir Francis Knollys, had fifteen children including Lettice Knollys, the second wife of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, the favorite of Elizabeth I. Catherine was a maid-of-honor to Henry VIII’s fourth and fifth wives, Anne of Cleves and Catherine Howard, and was the Chief Lady of the Bedchamber to her first cousin Queen Elizabeth I.

- Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon (1526 – 1596), married Anne Morgan, had sixteen children. Henry was Lord Chamberlain of the Household of his first cousin Queen Elizabeth I and patron of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, William Shakespeare’s company of actors.

Although Anne Boleyn refused to be Henry VIII’s mistress, she still wielded some power. William Carey had left Mary with considerable debts and so Anne decided to help out. Henry VIII granted Anne Boleyn the wardship of her nephew Henry Carey and Anne then arranged for him to be educated at a Cistercian monastery. Anne also interceded to secure her Mary an annual pension of £100.

In 1532, Mary was in the party of the 200 people who accompanied King Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn to France to meet with King François I of France so that the French king might show his public support and approval for the annulment of Henry’s first marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Also among the party was William Stafford, a soldier and the younger son of Sir Humphrey Stafford, an Essex landowner.

With her connections to King Henry VIII’s court and being the eldest daughter of Thomas Boleyn, who was by then 1st Earl Wiltshire, 1st Earl of Ormonde, and 1st Viscount Rochford, Mary had excellent prospects for a second marriage. However, in 1534, Mary and William Stafford secretly married. When Mary became pregnant, the marriage was discovered. Mary’s sister, now Queen Anne, was furious, the Boleyn family disowned Mary, and the couple was banished from court. It is thought that Mary gave birth to a son sometime in 1535 and that he died in 1545. There may also have been a daughter named Anne.

Because Mary’s financial situation was so poor after she and her husband had been banished from court, she begged Thomas Cromwell, then Henry VIII’s principal secretary, to speak to Henry VIII and her sister Anne on her behalf. After Henry VIII showed no interest in her situation, Mary asked Cromwell to speak with her family but they remained steadfast in their prior decision to disown Mary. It was Anne who finally relented and provided her sister with some financial support but she refused to reinstate Mary to her position at court. It is thought Mary and Anne never met again.

Mary’s sister Anne Boleyn, Queen of England; Credit – Wikipedia

The situation of Queen Anne herself quickly declined. When Anne gave birth in 1533 to her first child, a daughter Elizabeth, Henry VIII was greatly disappointed. By late 1535, Anne was pregnant again. However, during a tournament in January 1536, Henry fell from his horse and was unconscious for hours. The stress resulted in premature labor, and Anne miscarried a son. The loss of this son sealed Anne’s fate. Henry was determined to be rid of her, and her fall and execution were engineered by Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s chief minister. Many historians believe that the case charging Anne with adultery with her brother George Boleyn and four other men (Francis Weston, Henry Norris, William Brereton, and Mark Smeaton) was completely fabricated. Her trial, presided over by her uncle Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, occurred at the Tower of London on May 15, 1536, and she was found guilty of adultery, incest, and high treason. On May 18, 1536, Anne’s brother and the four other men were executed and Anne was executed the following day.

Very little is known about Mary’s life between 1534, when she was banished from court, and the executions of her brother George and sister Anne in May 1536. There is no record of Mary visiting or writing to her parents. She did not visit her sister or brother while they were imprisoned in the Tower of London and there is no evidence that she wrote to them. Like her uncle, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, Mary must have thought it wise to avoid any connection with her disgraced relatives.

Rochford Hall, now the clubhouse of the Rochford Hundred Golf Club; Credit – Wikipedia

After the death of her parents (mother in 1538 and father in 1539), Mary inherited some of the family’s estates in Essex, England including Rochford Hall. She lived there for the rest of her life, in better financial circumstances, with her husband William Stafford, who survived her and married again. Mary died of unknown causes, on July 19, 1543, in her early forties and her burial place is unknown.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Mary Boleyn. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Boleyn> [Accessed 2 August 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. William Stafford (Courtier). [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Stafford_(courtier)> [Accessed 2 August 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. William Carey (Courtier). [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Carey_(courtier)> [Accessed 2 August 2020].

- Erickson, Carolly, 2004. Great Harry. London: Robson.

- Flantzer, Susan, 2016. Anne Boleyn, Queen Of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/anne-boleyn-queen-of-england/> [Accessed 2 August 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2015. King Henry VIII Of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-henry-viii-of-england/> [Accessed 2 August 2020].

- No.wikipedia.org. 2020. Mary Boleyn. [online] Available at: <https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Boleyn> [Accessed 2 August 2020].

- Weir, Alison, 2001. Henry VIII – The King And His Court. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Weir, Alison, 2012. The Six Wives Of Henry VIII. [United States]: Paw Prints.