by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

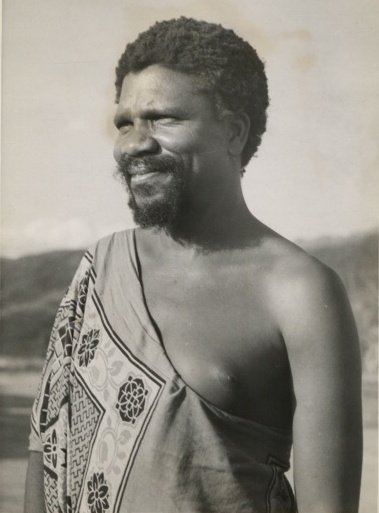

King Moshoeshoe II of Lesotho; Credit – Wikipedia

Moshoeshoe II was Paramount Chief of Basutoland from 1960 – 1965 and King of Lesotho from 1965 – 1990. The Kingdom of Lesotho is a country completely within the borders of South Africa. From 1822 – 1868, Lesotho was called Basutoland and was ruled by King Moshoeshoe I, the son of a minor tribal chief. In 1868, Basutoland became a British Crown Colony. Kings and then Paramount Chiefs still held power in Basutoland during the period of British colonization. During British colonization, the native rulers were known as Paramount Chiefs. Basutoland gained independence from the United Kingdom and became the Kingdom of Lesotho in 1966. King Moshoeshoe II was the first King of the independent country of Lesotho.

King Moshoeshoe II of Lesotho was born as Constantine Bereng Seeiso on May 2, 1938, in Morija, Basutoland now in Lesotho. Known as Bereng, his father was Simon Seeiso Griffith (1905 – 1940), Paramount Chief of Basutoland, and his mother was his father’s second wife Mabereng, a woman from the Batlokoa tribe. Bereng had one younger full brother Mathealia, one half-sister Ntšebo from his father’s first marriage to Mantšebo, and one younger half-brother Leshoboro from his father’s third marriage to Maleshoboro. His father Simon Seeiso Griffith died on December 26, 1940, at the age of 35. Although the official medical records say he died of gangrene, it is commonly believed that he was poisoned.

After Simon Seeiso Griffith died in 1940, his first and senior wife Mantšebo (1902 – 1964) became the ruler of Basutoland from 1941 – 1960, as the regent for her two-year-old stepson Bereng, the future Moshoeshoe II. Mantšebo was also made the guardian of Bereng. Mantšebo and Bereng’s mother Mabereng hated each other. Mabereng and her supporters kept Bereng away from the direct control of the regent Mantšebo because they feared she might have him killed.

Embed from Getty Images

British Commonwealth delegates Kghari Seghela (Chief of the Bakwena Tribe), King Sobhuza II of Swaziland and the future King Moshoeshoe II of Lesotho arrive in London to attend the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

As Bereng grew older, his mother began to have more of a say in his affairs. She arranged to have him raised in her Roman Catholic faith and rejected a plan to have him taught at a non-denominational government school. Instead, from 1948 – 1954, Bereng attended the Roman Catholic Roma Primary School in Roma, founded around 1860 as the first Catholic mission station in what is now Lesotho. Further conflict over schooling resulted in a full-scale war between the royal widows which only ended when Bereng left Lesotho to continue his education in the United Kingdom. There he attended Ampleforth College, run by the Benedictine monks, in North Yorkshire, England for his secondary education from 1954 – 1957. Bereng then studied Political Science, Philosophy, and Economics at Corpus Christi College, Oxford University until 1960.

Embed from Getty Images

King Moshoeshoe II, circa 1970

Initially, it was planned that Bereng would take on his role as Paramount Chief of Basutoland at the age of 25. However, a dispute with Mantšebo, the regent, led him to take over the office three years earlier than planned with the support of most of the other tribal chiefs. On March 12, 1960, Bereng took the name of his great-great-grandfather Moshoeshoe I and was sworn in as Moshoeshoe II, Paramount Chief of Basutoland, still a British protectorate. On April 30, 1965, Basotholand became an autonomous kingdom and Moshoeshoe II became king. Basutoland became an independent kingdom under the name of Lesotho on October 4, 1966.

In August 1962, Moshoeshoe II married Tabitha ‘Masentle Lerotholi Mojela (1941 – 2003), daughter of Lerotholi Mojela, Chief of Tsakholo. After her marriage, she was known as Queen Mamohato. The couple had three children:

- King Letsie III of Lesotho (David Mohato Bereng Seeiso) (born 1963), married Anna Karabo Mots’oeneng (Queen Masenate Mohato Seeiso), had two daughters and one son

- Prince Seeiso Bereng Seeiso (born 1966), married Machaka Makara (Princess Mabereng Seeiso), had two sons and one daughter

- Princess Constance Christina Maseeiso (1969-1994)

In 1970, a conflict arose between King Moshoeshoe II and Prime Minister Joseph Leabua Jonathan. The opposition and the king disagreed with Prime Minister Jonathan’s decision to suspend parliament and invalidate the election results, which had been unfavorable for the prime minister. In February 1970, Moshoeshoe II fled to the Netherlands and his wife Mamohato took over as regent. It was not until December 5, 1970, that the king, after promising not to interfere in politics again, was allowed to return to Lesotho.

In January 1986, Prime Minister Jonathan was overthrown in a military coup. The new leader, Major General Justin Metsing Lekhanya, gave the king some legislative and executive duties. However, the king came into conflict with Lekhanya when he admitted that he had single-handedly shot a student and expelled African National Congress (ANC) members from Lesotho.

In February 1990, Moshoeshoe fled to the United Kingdom, and in December 1990, he was deposed and his elder son became king, taking the name Letsie in honor of Letsie I, the eldest son of King Moshoeshoe I, the founder of the Basotho nation. In 1991, Lekhanya lost power and the new army chief, Colonel Elias Phisoana Ramaema, allowed Moshoeshoe to return to Lesotho as a citizen. King Letsie III, who was embarrassed at being king while his father was still alive, tried in vain to persuade the government to reinstate his father as king, and in August 1994 he enacted a new coup d’état with the army. Having obtained power, Letsie promised to return it to the previous government on the condition that Moshoeshoe II would return to being King of Lesotho, achieving this result in 1995.

Embed from Getty Images

President Nelson Mandela of South Africa (left) appears with King Moshoeshoe II (right) during his state visit to Lesotho, July 12, 1995

King Moshoeshoe II’s second reign was brief. In the Maloti Mountains in Lesotho, 57-year-old Moshoeshoe’s car plunged off a mountain road during the early hours of January 15, 1996. The accident also killed his chauffeur. King Moshoeshoe had left at 1:00 AM for a late-night visit to his cattle herds in the royal village at Matsieng. In rural southern Africa, cattle are the prime measure of wealth, so a government statement that the king set out at 1:00 AM to visit his cattle was not a surprise.

Tens of thousands of people attended the funeral ceremony. The procession stretched for miles along the road from the king’s favorite farm in Matsieng to Thaba Bosiu, the birthplace of the Basotho nation, and the burial place of its kings. Behind the king’s coffin, wrapped in the royal standard and borne on a gun carriage, came the limousines of diplomats and dignitaries. Among those attending were Presidents Nelson Mandela of South Africa, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, Frederick Chiluba of Zambia, and Ketumile Masire of Botswana – the leaders of southern Africa’s big powers. King Moshoeshoe II was buried at Thaba Bosiu, the stronghold of King Moshoeshoe I (reigned 1822 – 1870) and once the capital of Basutoland.

Grave of King Moshoeshoe II; Credit – https://sedativegunk.com

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. 2020. Moshoeshoe II.. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moshoeshoe_II.> [Accessed 24 August 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. ‘Mantšebo. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%27Mant%C5%A1ebo> [Accessed 24 August 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Moshoeshoe II Of Lesotho. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moshoeshoe_II_of_Lesotho> [Accessed 25 August 2020].

- Nl.wikipedia.org. 2020. Moshoeshoe II Van Lesotho. [online] Available at: <https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moshoeshoe_II_van_Lesotho> [Accessed 25 August 2020].

- The Independent. 1996. Lesotho Buries Its Stormy King. [online] Available at: <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/lesotho-buries-its-stormy-king-1325989.html> [Accessed 25 August 2020].

- Timesmachine.nytimes.com. 1996. King Of Tiny Land Circled By South Africa Dies In Car Plunge. [online] Available at: <https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1996/01/16/076350.html?pageNumber=4> [Accessed 25 August 2020].

- Washington Post. 1996. King Moshoeshoe II Dies At 57. [online] Available at: <https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1996/01/16/king-moshoeshoe-ii-dies-at-57/8734198f-b7db-4c18-a9c0-ce0efc1cc147/> [Accessed 25 August 2020].