by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Queen’s Chapel, St James’s Palace; Credit – By Steve Cadman – https://www.flickr.com/photos/stevecadman/411794867/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50925591

The Queen’s Chapel is located on Marlborough Road which runs between The Mall and Pall Mall in London. It is across from St. James’s Palace, adjacent to Marlborough House, and a very short distance from Buckingham Palace. The Queen’s Chapel is a royal peculiar, a Church of England parish or church under the direct jurisdiction of the monarch rather than the jurisdiction of a bishop.

The Queen’s Chapel was begun in 1623, as a consequence of the proposed marriage between Charles, Prince of Wales, the future King Charles I of England and son of King James I of England, and Infanta Maria Anna of Spain, daughter of King Felipe III of Spain. In 1622, King James I received an offer of marriage from King Felipe IV of Spain, brother of Maria Anna, to strengthen the relations between England and Spain. Active marriage negotiations began but ultimately Maria Anna did not wish to marry a Protestant and Charles would not convert to Catholicism. Officially, the wedding never took place due to political reasons and because of the reluctance of King Felipe IV to make a dynastic marriage with the House of Stuart.

Inigo Jones, the architect of the Queen’s Chapel; Credit – Wikipedia

Since England was Protestant, Maria Anna would have needed a Roman Catholic chapel for worship, and so planning for a chapel accessible from St. James’s Palace in London began during the marriage negotiations. Special dispensation was given to construct the chapel as at that time the construction of Roman Catholic churches was prohibited in England. The Queen’s Chapel was designed by Inigo Jones, the first significant English architect of the early modern period. Parts of the design for the Queen’s Chapel were inspired by the Pantheon of ancient Rome and Jones intended the church to evoke the Roman temple. The foundation stone was laid on May 30, 1623.

Henrietta Maria of France, Queen of England; Credit – Wikipedia

While King Charles I did not marry Infanta Maria Anna of Spain, he did marry another Roman Catholic princess, Henrietta Maria of France, the youngest of the six children of King Henri IV of France and his second wife Marie de’ Medici, and the sister of King Louis XIII of France. In 1625, Henrietta Maria arrived in England with over 400 attendants including 29 priests and a bishop. Parliament was outraged to discover that secret terms of the marriage contract permitted the daily celebration of the Catholic Mass. Charles I insisted on the rapid completion of the Queen’s Chapel to accommodate Henrietta Maria’s religious needs.

During the English Civil War (1642–1651), Parliament passed an ordinance demanding that the Royal Chapels be “cleansed from all Popish Reliques and superstitions.” The Queen’s Chapel was looted and much of the interior suffered damage. During the Commonwealth of England (1649 – 1660), when England was governed as a republic, the Queen’s Chapel was used as a stable.

Catherine of Braganza, Queen of England; Credit – Wikipedia

in 1660, upon the Restoration of the monarchy, the son of the beheaded King Charles I returned to England to reign as King Charles II of England. The Roman Catholic Catherine of Braganza, daughter of King João IV of Portugal, had first been suggested as a bride for the future King Charles II in 1645 during the reign of Charles II’s father King Charles I of England, and again in 1660 when the monarchy was restored in England. Already there were rumors of Catherine’s inability to have children – her marriage to Charles II turned out to be childless – but the newly restored King Charles II was eager to have her £300,000 dowry. Catherine arrived in England in 1662. According to the marriage treaty, Catherine was to be provided with “a private Chapel in her residence with the right to practice her Catholic religion,” and Charles II commenced work on the restoration of the Queen’s Chapel for Catherine’s use.

Maria Beatrice of Modena, Queen of England; Credit – Wikipedia

King Charles II’s brother, James, Duke of York, the future King James II of England, had secretly converted to Catholicism sometime after his first marriage to Anne Hyde who had also converted to Catholicism. After Anne’s death in 1671, King Charles II allowed his brother James to make a second marriage with the fifteen-year-old Catholic Maria Beatrice of Modena in 1673. Maria Beatrice’s deeply pious Catholicism could be expressed within the seclusion of the Queen’s Chapel where she and her husband James could practice their Roman Catholicism without public scrutiny. When the childless Charles II died in 1685, his brother succeeded him as King James II of England.

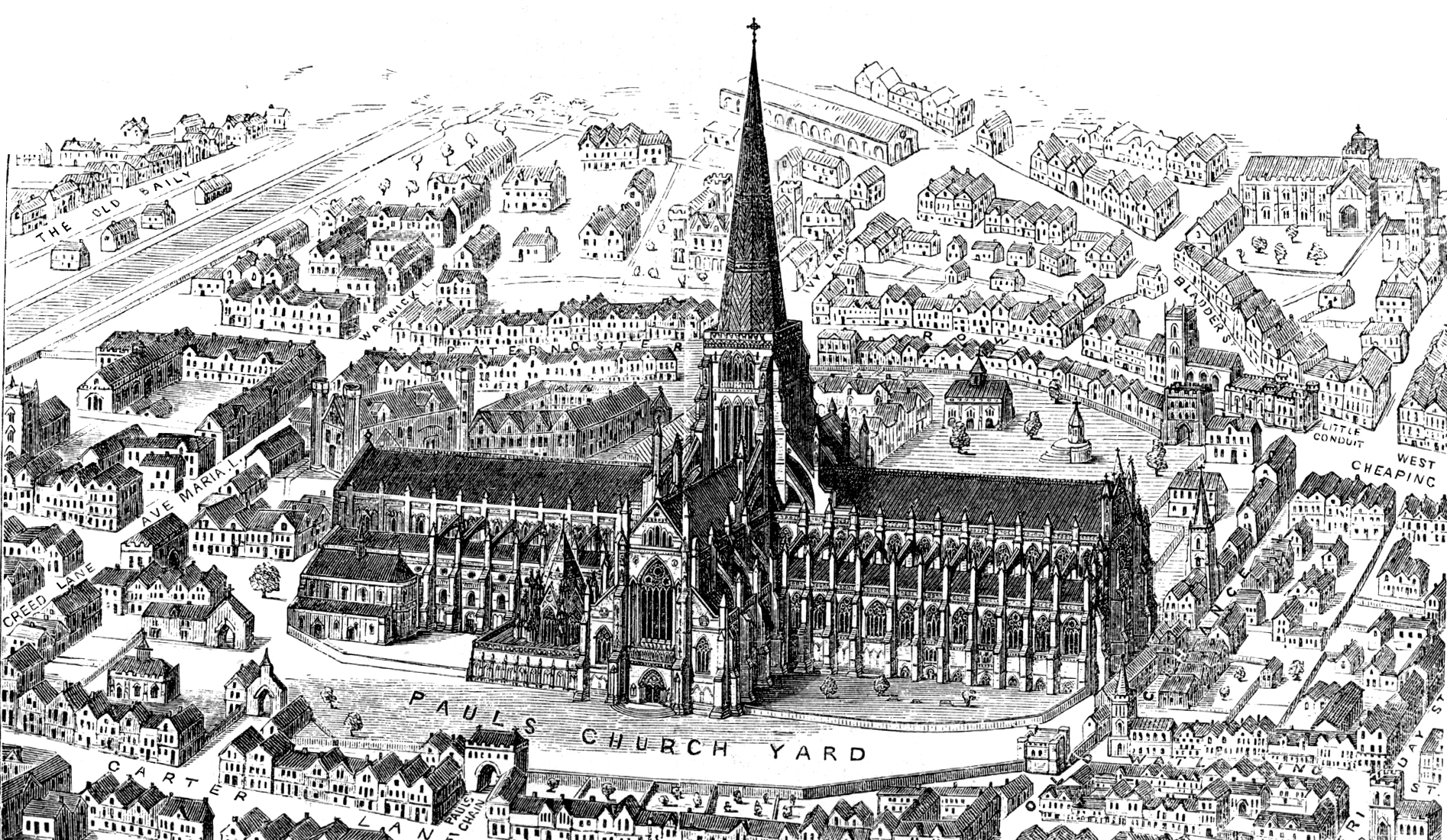

The Queen’s Chapel in 1688; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1688, the Catholic King James II was overthrown in the Glorious Revolution. He was replaced by his Protestant daughter Mary from his first marriage and her Protestant husband and first cousin Willem III, Prince of Orange who reigned jointly as King William III and Queen Mary II. Almost immediately, the Queen’s Chapel was purged of all traces of Roman Catholicism. The interior was stripped of its statues, relics, side altars, and paintings. William and Mary were unsure what to do with the Queen’s Chapel. They may have considered its demolition or its conversion to another purpose. Ultimately, it was decided to grant the use of the Queen’s Chapel to French Protestants who had settled in London to escape religious persecution in France.

The German Chapel in 1819; Credit – Wikipedia

By 1781, there was no longer a need for a French Protestant chapel. Instead, a group of Hanoverian Lutherans whose families had come from Hanover when King George I became king was granted the use of the Queen’s Chapel. The name of the chapel changed to the German Chapel.

In 1809, a fire destroyed the royal apartments adjacent to the German Chapel. Instead of rebuilding the royal apartments, King George III decided to connect Pall Mall with The Mall by building Marlborough Road right through the site of the destroyed royal apartments. This cut off the chapel from St. James’s Palace and placed a physical barrier, Marlborough Road, between the royal residence and the chapel. The chapel now appeared to be connected not to St. James’s Palace but rather to Marlborough House, the London townhouse of the Dukes of Marlborough.

Alexandra of Denmark, Princess of Wales, later Queen Alexandra; Credit – Wikipedia

The German Chapel continued to exist under the patronage of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert, born a Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, now in Germany, but this lasted only until Prince Albert died in 1861. After the death of George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough in 1817, the ownership of Marlborough House had been taken over by The Crown. After their marriage in 1861, The Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII) and his Danish wife Princess Alexandra made Marlborough House their home. Because the Queen’s Chapel was so close to Marlborough House, Alexandra used it as a private chapel. After 1881, the Queen’s Chapel became a Danish community church. After Queen Victoria died in 1901, the name of the chapel was changed to the Marlborough House Chapel and the Danish Church had exclusive use.

The chapel was closed in 1938 for its first major restoration since William III and Mary II had purged its Catholic past. The original name, the Queen’s Chapel, was restored in 1939. Restoration work stopped during World War II and was not fully completed until 1951. Although used regularly for weekly Sunday services for the public from Easter until October, the Queen’s Chapel no longer plays a major role in the life of the British royal family.

Recent Royal Events

Queen Elizabeth II after the funeral service for Margaret (Bobo) MacDonald

Margaret “Bobo” MacDonald, who died on September 22, 1993, was a member of the royal household since 1930 and was the nanny, dresser, and confidante of Queen Elizabeth II. From 1930 onward, Bobo was closer to Elizabeth than anyone outside her family. In her later years, Bobo held a unique position in Buckingham Palace. She had her own suite, no duties, and enjoyed a closer personal friendship with Queen Elizabeth II than nearly anyone else, including some of the members of the royal family. She was given a funeral on September 30, 1993, at the Queen’s Chapel attended by Queen Elizabeth II.

Embed from Getty Images

The coffin of Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon lying in rest at the Queen’s Chapel

Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon, daughter of King George VI and sister of Queen Elizabeth II: After her death at King Edward VII’s Hospital, London, on February 9, 2002, Princess Margaret’s coffin was initially taken to Kensington Palace. Her coffin then rested at the Queen’s Chapel February 12, 2002 – February 14, 2002, to enable her family and friends to pay their respects privately before the coffin was transferred to St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle for the funeral.

The Sub-Dean of the Chapels Royal, Reverend Willie Booth, kneels in prayer at the coffin of Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother in the Queen’s Chapel

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, wife of King George VI and mother of Queen Elizabeth II: After her death on March 30, 2002, at her home, Royal Lodge in Windsor Great Park, her coffin rested in the Royal Chapel of All Saints, Windsor Great Park until April 2, 2002, when it was taken to the Queen’s Chapel at St. James’s Palace where it rested to enable members of the royal family to their respects privately before the coffin was transferred to lie in state at Westminster Hall on April 5, 2002.

Alexander Windsor, Earl of Ulster, son of Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester, married Claire Alexandra Booth on June 22, 2002, at the Queen’s Chapel

Lady Rose Windsor and her husband leave the Queen’s Chapel after their wedding

Lady Rose Windsor, daughter of Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester, married George Gilman on July 19, 2008, at the Queen’s Chapel

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Queen’s Chapel – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen%27s_Chapel> [Accessed 1 May 2021].

- Leyden, Kyle, 2015. Consorting with the Enemy: The Queen’s Chapel at St James’s Palace. [online] VITRUVIUS HIBERNICUS. Available at: <https://kyleleyden.wordpress.com/2015/01/24/consorting-with-the-enemy-the-queens-chapel-at-st-jamess-palace/> [Accessed 1 May 2021].

- Timms, Elizabeth, 2018. The Queen’s Chapel, St James’s. [online] Royal Central. Available at: <https://royalcentral.co.uk/features/the-queens-chapel-st-jamess-102570/> [Accessed 1 May 2021].

- Unofficial Royalty. 2021. Unofficial Royalty. [online] Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/> [Accessed 1 May 2021]. (various articles)