by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2025

Statue of Valdemar I, King of Denmark in Ringsted, Denmark; Credit – Wikipedia

Valdemar I, King of Denmark, who reigned from 1154 to 1182, was the son of Saint Cnut Lavard, Duke of Schleswig, and Ingeborg of Kiev. His paternal grandparents were King Eric I of Denmark and Bodil Thurgotsdatter. Valdemar’s maternal grandparents were Grand Prince Mstislav I of Kiev and Christina Ingesdotter of Sweden. Valdemar was born January 14, 1131, just seven days after his father was murdered. He was named after his mother’s grandfather, Vladimir II Monomakh, Grand Prince of Kiev.

Valdemar’s father Cnut Lavard, Duke of Schleswig; Credit – Wikipedia

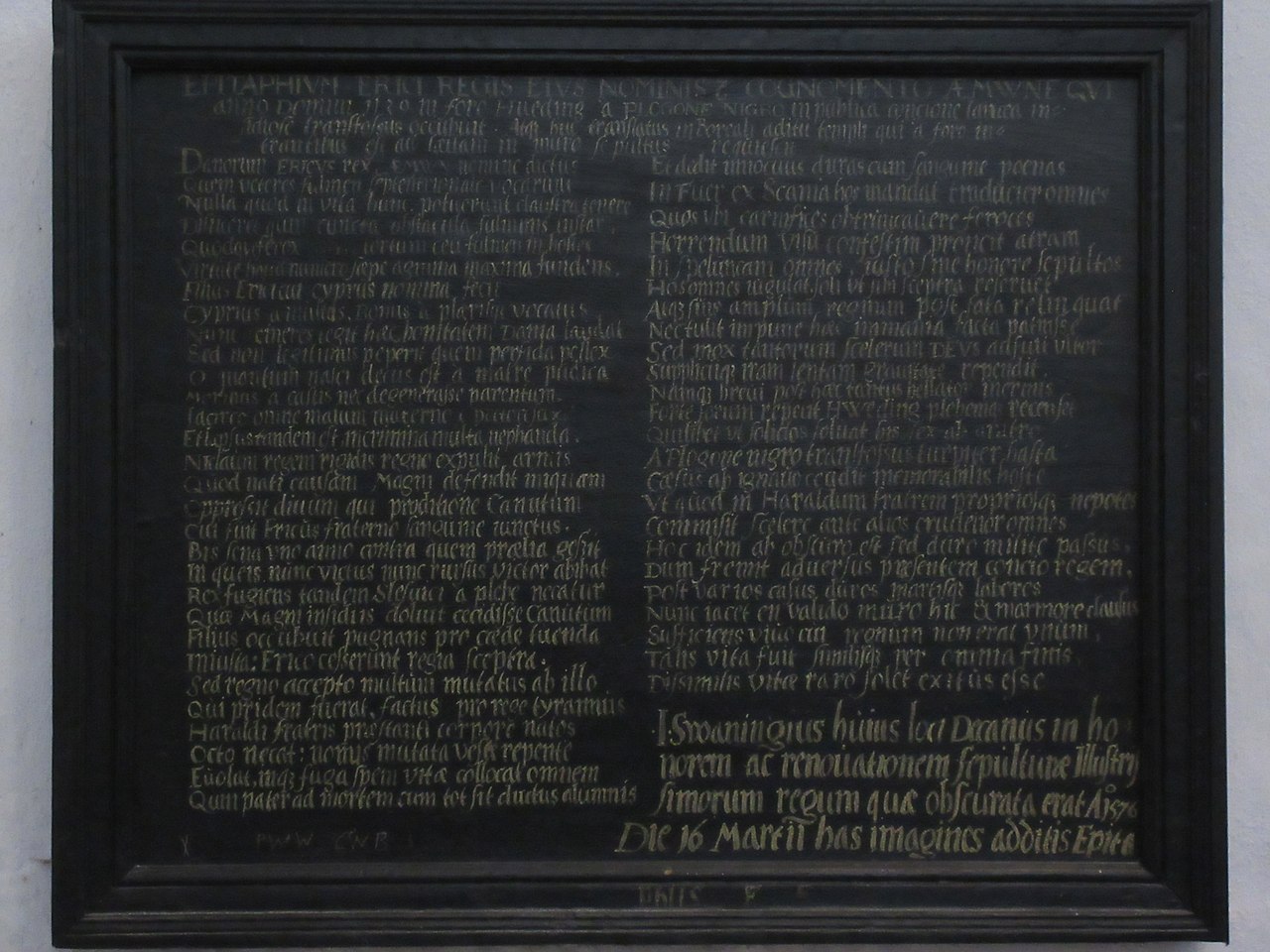

On January 7, 1131, Valdemar’s father, Cnut Lavard, Duke of Schleswig, was killed by his cousin Magnus the Strong, the son of King Niels of Denmark, because Magnus saw Cnut Lavard as a rival to the Danish throne. The murder of Cnut Lavard started several years of civil war between King Niels and his son Magnus against Cnut Lavard’s illegitimate half-brother Eric Emune, the future Eric II, King of Denmark.

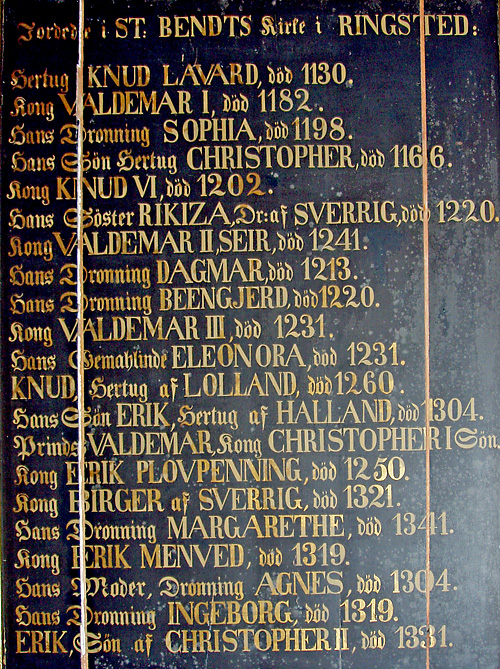

Valdemar’s paternal uncle, King Eric II of Denmark, started the canonization process of his half-brother Cnut Lavard by establishing Ringstead Abbey in the same Danish town as St. Bendt’s Church, where Cnut Lavard was buried. The monks at Ringstead Abbey were to document reports of miracles at Cnut Lavard’s grave. Cnut Lavard was canonized as a saint, but not until 1170, thirty-three years after Eric II died.

Valdemar grew up at the court of Asser Rig, a Zealand chieftain from the Hvide family, with Asser Rig’s sons Esbern Snare (later a royal chancellor and chieftain) and Absalon (later Bishop of Roskilde and then Archbishop of Lund). Asser Rig had been raised with Valdemar’s father, Cnut Lavard, and his sons, Esbern and Absalon, were Valdemar’s lifelong friends and advisors.

In 1146, Eric III, King of Denmark became seriously ill and abdicated. Sweyn Grathe (Sweyn III), son of Eric II, King of Denmark, was elected King of Denmark by the nobles in Zealand, and Cnut Magnusson (Cnut V), son of Magnus (the Strong) Nielsen, was elected King of Denmark by the nobles in Jutland. For eleven years, there was a civil war, the Feud of 1146 – 1157, for the control of the Kingdom of Denmark, fought between King Sweyn III, King Cnut V, and Valdemar. In 1154, Cnut V joined with Valdemar and were recognized as Co-Kings. In July 1157, Sweyn III, Cnut V, and Valdemar I agreed to divide the Kingdom of Denmark between the three of them and serve as Co-Kings. This agreement barely lasted for a month.

The murder of Cnut V, King of Denmark at the Blood Feast of Roskilde; Credit – Wikipedia

On August 9, 1157, in what was supposed to be a reconciliation feast at Cnut V’s royal estate in Roskilde, Denmark, Sweyn III attempted to assassinate his rivals, Cnut V and Valdemar I. According to the Danish historian, theologian, and author Saxo Grammaticus (circa 1160 – after 1208), Sweyn III had planned the murder of his rivals and had his men carry out the attack. Cnut V, aged about twenty-eight, was killed, but Valdemar I escaped, although he was wounded. This incident, known as the Blood Feast of Roskilde, is a significant historical event in Danish history.

Valdemar I defeated Sweyn III in the Battle of Grathe Heath on October 23, 1157. After the battle, while fleeing from the battlefield, Sweyn III was killed by a group of peasants. Having survived his rival pretenders to the Danish throne, Valdemar I became the sole King of Denmark, reigning until he died in 1182.

In 1157, in Viborg, Denmark, Valdemar I, King of Denmark married Sophia of Minsk, the daughter of Volodar Glebovich, Prince of Minsk and Richeza of Poland.

Valdemar I and Sophia had nine children:

- Sophia of Denmark (1159 – 1208), married Siegfried III, Count of Weimar-Orlamünde, had two sons

- Cnut VI, King of Denmark (1163 – 1202), married Gertrude of Bavaria, no children

- Maria of Denmark (circa 1165 – ?), became a nun at Roskilde

- Margaret of Denmark (circa 1167 – circa 1205), became a nun at Roskilde

- Valdemar II, King of Denmark (1170 – 1241), married (1) Dagmar of Bohemia, had one son who predeceased his father, Dagmar died giving birth to a stillborn son (2) Berengaria of Portugal, had three sons who were all King of Denmark (Eric IV, Abel, and Christopher I), and one daughter, Berengaria died giving birth to a stillborn child

- Ingeborg of Denmark (1174 – 1237), married King Philip II of France, no children. Philip asked the Pope several times for an annulment but was always denied.

- Helena of Denmark (circa 1176 – 1233), married Wilhelm, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, had one son

- Rikissa of Denmark (circa 1178 – 1220), married King Eric X of Sweden, had one son and four daughters

- Walburgis of Denmark (? – 1177), married Bogusław I, Duke of Pomerania, had two sons

In 1158, Valdemar’s childhood friend Absalon was elected Bishop of Roskilde, and Valdemar made him his chief advisor. After the past internal conflict in Denmark, Valdemar instituted a policy of internal reconciliation. He reorganized and rebuilt war-torn Denmark. He strengthened the fortifications in the south, building military installations to control the straits along the Baltic Sea. Valdemar was successful in making the Danish monarchy hereditary, abolishing the elective monarchy. He was recognized as hereditary king by Pope Alexander III in 1165. Valdemar reinforced this by having his son, Canute VI, proclaimed as co-king in 1166.

Saint Bendt’s Church; Credit – Wikipedia by Mariusz Paździora

From 1161 to 1170, under Valdemar I’s patronage, a new church, Saint Bendt’s Church, was built in Ringsted, Denmark, where his martyred father, Saint Cnut Lavard, was buried at the Ringsted Monastery church. The still unfinished church was consecrated on June 25, 1170. At the consecration, Eskil, Archbishop of Lund, laid to rest Saint Cnut Lavard’s remains in a magnificent gold casket in a chapel behind the high altar and crowned King Valdemar I’s seven-year-old son, King Cnut VI, as co-king and heir to the throne. St. Bendt’s Church served as the center of worship for King Valdemar I’s father, Saint Cnut Lavard.

Grave of Valdemar I, King of Denmark at St. Bendt’s Church; Credit – Wikipedia by Oleryhlolsson – Own work

Valdemar I, King of Denmark died, aged fifty-one, on May 12, 1182, at Vordingborg Castle in Vordingborg, Denmark. His remains were transported to Ringsted, Denmark, where peasants carried his body to Saint Bendt’s Church for burial. There, King Valdemar I lies in rest with his father Cnut Lavard, his wife Sophia of Minsk, Queen of Denmark, his son Cnut VI, King of Denmark, his daughter Rikissa of Denmark, Queen of Sweden, and his son Valdemar II, King of Denmark.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2011). König von Dänemark. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waldemar_I._(D%C3%A4nemark)

- Bidragsydere til Wikimedia-projekter. (2003). Konge af Danmark (1131-1182). Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valdemar_den_Store

- Flantzer, Susan. (2025). Cnut V, King of Denmark [Review of Cnut V, King of Denmark]. Unofficial Royalty. https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/cnut-v-king-of-denmark/

- Flantzer, Susan. (2025). Saint Bendt’s Church in Ringsted, Denmark [Review of Saint Bendt’s Church in Ringsted, Denmark]. Unofficial Royalty. https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/saint-bendts-church-in-ringsted-denmark/

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2025). Valdemar I of Denmark. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation.