by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2018

Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Sir James Reid, 1st Baronet served Queen Victoria as Resident Physician 1881 – 1889 and Physician-in-Ordinary 1889 – 1901. He also served King Edward VII and King George V as Physician-in-Ordinary.

Born in Ellon, Aberdeenshire, Scotland on October 23, 1849, Sir James Reid, 1st Baronet was the son of James Reid, the local doctor in Ellon, and Beatrice Peter whose father was the steward of the Earl of Kintore. Born and bred at The Chestnuts, which was to be his home for his entire life (although he was rarely there while serving Queen Victoria), young James observed his father at work as a country doctor, going out at all hours to treat people and sometimes animals.

Reid had one younger brother:

- John Peter Reid (1851 – 1916), married Mary Peter

Reid was first educated at the local school in Ellon and then at the Aberdeen Grammar School where graduated in 1865 with the Gold Medal for being the best student. Reid wanted to be a doctor like his father but at sixteen he was too young to embark on that career and so he enrolled in a liberal arts program at Aberdeen University. Three years later, he graduated, once again with the Gold Medal. Reid then enrolled in the medical school at the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. He was again at the top of his class and won first prize in Botany, Chemistry, Materia Medica (now termed pharmacology), Anatomy, Zoology, Physiology, Surgery, Midwifery, and Medical Jurisprudence.

After graduating from medical school in 1872, Reid went to London and joined the practice of Dr. William Vacy Lyle in Paddington. He gained much experience there but became restless with his prospects. In 1874, Reid left Dr. Vacy Lyle’s practice for travel and study in continental Europe. He settled in Vienna, Austria where he studied with prestigious professors at the Vienna General Hospital. In 1877, Reid returned to Scotland to work with his father in his practice. He spent four years working with his father before reaching a turning point in 1881.

Queen Victoria was looking for a Resident Medical Attendant for herself and the royal household. The Queen required that the doctor be a Scotsman, preferably from Aberdeenshire where her beloved Balmoral, the home she had built with her late husband Prince Albert, was located. She further required that the doctor be highly qualified and fluent in German. The hiring was to be done via The Queen’s Commissioner at Balmoral and Reid’s maternal uncle the Reverend George Peters was one of the people approached for recommendations. Reid met with The Queen’s Commissioner in Aberdeen and then received notice that he was to meet with Queen Victoria at Balmoral.

On June 8, 1881, Reid went to Balmoral and met with Queen Victoria. After her meeting with Reid, she wrote in her journal: “8 June: Saw Dr. Reid from Ellon, who has the very highest testimonials, having taken very high honors at Aberdeen and studied for two years at Vienna; he also practiced a short time in London and is now helping his father at Ellon, who has been a doctor there for many years. He is willing to come for a time or permanently in Dr. Marshall’s place.”

However, Reid could not be hired without the approval of Sir William Jenner, Queen Victoria’s Physician-in- Ordinary. Reid was interviewed by Jenner in London on June 11, 1881, and Jenner gave his approval. On July 8, 1881, 31-year-old Dr. James Reid arrived at Windsor Castle to start a career that would only end with his death in 1923.

Over the years, Reid became not only Queen Victoria’s doctor but her adviser and confidant. Except when he was on leave, he was always at court and he always traveled with her in the United Kingdom and throughout Europe. On August 28, 1897, Reid was created 1st Baronet Reid of Ellon, Aberdeenshire, a Baronetcy that continues to this day.

As Reid was approaching the age of fifty, he still had not married. While serving Queen Victoria, he realized that if he were to successfully serve The Queen, there was no room for a wife. He had seen how the marriages of other male household staff had suffered. Reid always traveled with The Queen and only left the court to spend a few weeks with his mother in Ellon. After he received his Baronetcy, his social situation improved and his careful savings would be able to furnish a country house for a wife.

Reid’s future wife is first mentioned in his diary on December 9, 1898: “…went to tea in Miss Bulteel’s rooms to meet Misses Baring, Ponsonby and Biddulph.” The Honorable Susan Baring, born in 1870, was the daughter of Edward Baring, 1st Baron Revelstoke and had been appointed one of Queen Victoria’s Maids of Honor in 1898. At age 29, Susan’s marriage prospects were looking dim.

On July 24, 1899, during a bicycle ride at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, 50-year-old Reid proposed to Susan and she consented. Reid and Susan knew Queen Victoria’s reaction would be problematic, and it was. The Queen regarded Reid as essential to her health and well-being. She had had his attention for nearly twenty years and was outraged that he felt the need to marry.

Harriet Phipps, Maid of Honor from 1862 – 1889 and Woman of the Bedchamber from 1889 until The Queen’s death in 1901, was the go-between for Reid and The Queen. Queen Victoria knew she could not prevent Reid and Susan from marrying but she intended to exert as much control of the situation as she could. She insisted that nothing be said about the engagement. Reid and Susan enlisted Princess Helena, Queen Victoria’s daughter to help. A month later, the engagement still had not been announced. Queen Victoria dictated to Harriet Phipps a paper outlining all the conditions to be observed after the marriage.

Queen Victoria demanded that Reid was to continue to live at court except when he was on leave. He was to come to see her after breakfast, before luncheon, and before he went out in the afternoon. If Reid wanted to dine out, he had to ask The Queen’s permission and had to return to court by 11 PM. Susan was not allowed in his rooms at Balmoral or Osborne House but could visit him occasionally in his rooms at Windsor Castle. Finally, on August 24, 1899, Queen Victoria consented to the announcement of the engagement.

Sir James Reid and The Honorable Susan Baring were married by Randall Davidson, Bishop of Winchester (later Archbishop of Canterbury) at St Paul’s Church in Knightsbridge, London on November 28, 1899. Three of Queen Victoria’s daughters – Helena, Louise, and Beatrice – attended as did many of the household staff and servants. Queen Victoria stayed at Windsor Castle. Almost immediately after the honeymoon began, Reid received a letter from Queen Victoria saying she was suffering from flatulence and indigestion, her shoulder hurt, her appetite was poor and the Boer War was causing her anxiety.

Reid and Susan had a happy marriage and had four children. Their eldest child Edward was the godson of King Edward VII. Whenever possible, they spent time at Reid’s birthplace The Chestnuts. Reid had joined together his father’s old house The Chestnuts and the house next door which was called Cosy Neuk to make a larger home. The home has since been converted into an apartment hotel.

- Sir Edward James Reid, 2nd Baronet (1901 – 1972), married Tatiana Fenoult, had one son and one daughter

- Admiral Sir John Peter Lorne Reid (1903 – 1973), married Jean Dundas, had one son and one daughter

- Margaret Cecilia Reid (1904 – 1937), unmarried

- Victoria Susan Beatrice Reid (1908 – 1997), married Leonard St. Clare Ingrams, had four sons

Queen Victoria on her deathbed possibly by Sir Hubert von Herkomer bromide print, 1901 6 5/8 in. x 9 1/8 in. (169 mm x 232 mm) Purchased, 1992 Photographs Collection NPG x38281

The last service Reid did for Queen Victoria was to carry out her written instructions in the event of her death. Victoria had finalized the instructions in December 1897, and sealed them in an envelope marked “For my Dressers to be opened directly after my death and to be always taken and kept by the one who may be traveling with me.” Victoria had chosen Reid to be responsible for her body until her coffin was sealed. He was determined to precisely follow Queen Victoria’s wishes.

Selina Tuck, known as Mrs. Tuck, was Queen Victoria’s head dresser and she privately read to Reid Victoria’s instructions and the list of items she wished to be placed in her coffin. Included in the instructions were the orders that some of the items were not to be seen by family members. With no family members present, Reid, Mrs. Tuck, and the junior dressers prepared the coffin and then set about arranging the items Queen Victoria wished to be placed in the coffin.

The items included favorite shawls and embroidered handkerchiefs, specified photos of family, friends, and servants, an alabaster cast of Prince Albert’s hand and his dressing gown, a robe that Princess Alice had embroidered, and other mementos, both priceless and mere baubles. A quilted cushion was laid over these items. The family then came into the room and Queen Victoria’s body was placed in the coffin.

Reid asked the family to leave the room and then with the assistance of Mrs. Tuck and the junior dressers, he performed the request that Queen Victoria wanted to keep secret from her family. First, Reid placed Victoria’s wedding veil over her face and upper torso. He then covered with tissue paper a photograph of John Brown, the Scots ghillie who had become her personal attendant, and a lock of Brown’s hair in a case, and then placed them into the Queen’s left hand. He covered the two items with the flowers that Queen Alexandra had placed in the coffin. The family then came into the room again for one last look before the coffin was sealed.

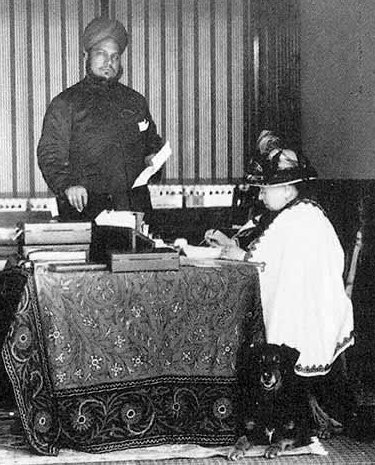

Sir James Reid, May 6, 1901; Photo Credit – http://lafayette.org.uk/rei2677.html

King Edward VII did not have a resident physician but gave Reid an annual pension for life of £1,000 and a sum of £210 per year to remain as Physician-in-Ordinary in a consultative capacity. Reid attended King Edward VII during his final illness in May 1910. He had been appointed Physician-in-Ordinary to King George V when he was Prince of Wales and continued to hold that position when George became King upon the death of his father in 1910. As he aged, Reid continued to serve King George V and his family but more and more infrequently.

The wedding of Prince Albert, Duke of York (the future King George VI) and Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in April 1923 was the last royal event Reid attended. In May 1923, he had an acute attack of phlebitis from which he never recovered. Sir James Reid, 1st Baronet died on June 29, 1923, in London at the age of 73. He had a simple funeral in his hometown of Ellon, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and was buried in the Ellon Cemetery. One of the wreaths was inscribed, “For our dear old friend, Sir James Reid, from Alexandra” was from Queen Alexandra, King Edward VII’s widow. Reid’s wife Susan survived her husband by 38 years, dying in 1961 at the age of 90.

Tomb of Sir James Reid and his wife Susan; Photo Credit – https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/157701736/james-reid

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Recommended Book – Serving Queen Victoria: Life in the Royal Household by Kate Hubbard

Works Cited

- Baird, Julia. Victoria The Queen. Random House, 2016.

- Erickson, Carolly. Her Little Majesty: The Life of Queen Victoria.Simon and Schuster, 1997.

- Hubbard, Kate. Serving Victoria: Life In The Royal Household. Harper Collins Publishers, 2012.

- Packard, Jerrold M. Farewell In Splendor: The Passing Of Queen Victoria And Her Age. Dutton, 1995.

- Reid, Michaela. Ask Sir James. Viking, 1987.

- “Sir James Reid”. Thepeerage.Com, 2018, http://www.thepeerage.com/p5204.htm#i52035. Accessed 5 June 2018.