by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2019

Engraving by John Simon; Credit – Wikipedia

Little Prince George William lived from November 13, 1717 – February 17, 1718, three months and four days, but an event in his short life caused a huge family argument. The principals in the argument were George William’s grandfather King George I of Great Britain and his father The Prince of Wales, the future King George II of Great Britain. It was the beginning of the battles between fathers and sons that would plague the House of Hanover. First, let us deal with Prince George William’s short life.

Prince George William of Great Britain was born at St. James’ Palace in London, England on November 13, 1717. His parents were the Prince and Princess of Wales, the future King George II and his wife, born Caroline of Ansbach. George William was the first of his parents’ eight children to be born in Great Britain. His four elder siblings, Frederick, Prince of Wales, Anne, Princess Royal, Princess Amelia, and Princess Caroline, had all been born in the Electorate of Hanover, now in Lower Saxony, Germany.

George William’s great-grandmother, Sophia of the Palatinate, Electress of Hanover was the heiress presumptive to Queen Anne of Great Britain in accordance with the Act of Settlement 1701, but Sophia died two months before Queen Anne died. Upon Queen Anne’s death on August 1, 1714, George William’s grandfather succeeded to the British throne as King George I of Great Britain and his father became the heir apparent to the British throne and was created Prince of Wales the following month.

In February 1718, Prince George William became ill. The infant prince died at about 8:00 PM on February 17, 1718, at Kensington Palace in London. The London Gazette officially reported that Prince George William “had been taken ill about ten days before of a cough and strainess of breathing, from which he had been recovering till the foggy weather on the 15th and 16th, which occasioning a relapse into his strainess of breathing, he fell into convulsions and died.” An autopsy determined that he had been born with a “polyp on his heart.”

On the night of February 23, 1718, Prince George William’s remains, accompanied by the king’s servants, the Yeomen of the Guard and the Horse Guards, were transported from Kensington Palace in one of King George I’s coaches to Westminster Abbey where he was privately interred. Francis Atterbury, Bishop of Rochester conducted the funeral service. It was not unusual for deceased royal children to be buried in this manner.

Backtracking to Prince George William’s christening: George William was christened at the Chapel Royal, St. James’s Palace in London, England on November 28, 1717, by John Robinson, Bishop of London. His godparents were:

- King George I of Great Britain: his paternal grandfather

- Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle: Lord Chamberlain of the King’s Household and later Prime Minister of Great Britain

- Diana Beauclerk, Duchess of St Albans: Mistress of the Robes to his mother, born Lady Diana de Vere, wife of Charles Beauclerk, 1st Duke of St Albans, an illegitimate son of King Charles II and his mistress Nell Gwynne

King George I, Prince George William’s grandfather; Credit – Wikipedia

What should have been a perfectly normal, quiet christening turned into a shouting match that resulted in the parents of Prince George William being exiled from their home at St. James’ Palace and their children being kept at St. James’ Palace in the custody of their grandfather King George I.

George. Prince of Wales, Prince George William’s father; Credit – Wikipedia

The Prince of Wales (George) asked his father King George I and his paternal uncle Prince Ernst August of Hanover, who had been created Duke of York, to be godfathers. The Princess of Wales (Caroline) wanted to name her son William and initially King George I agreed. However, the little prince was the first of the British House of Hanover to be born in Great Britain, and apparently, the king’s government ministers insisted that the previous protocol be followed. The ministers told the king that since he was one of the godfathers, the infant prince should be named George. A compromise was reached and the prince’s name would be George William.

Caroline, Princess of Wales, mother of Prince George William; Credit – Wikipedia

Next, the ministers objected to Prince Ernst August of Hanover being one of the godparents. He was the reigning Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück (now in Lower Saxony, Germany) and unmarried. If Ernst August was named a godparent, he perhaps might make the British prince the heir to his German title. Furthermore, the ministers advised the king that it was usual practice for the Lord Chamberlain, the most senior officer of the Royal Household, to be one of the godfathers. This writer, who has researched and written about Royal Christenings, can say that although the list of godparents for the British House of Stuart which preceded the House of Hanover is incomplete, there is no evidence that it was the usual practice for the Lord Chamberlain to be a royal godfather. Caroline was willing to compromise again and suggested that the Lord Chamberlain, Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, could stand as proxy for Ernst August. Caroline was overruled by the ministers and then asked for the christening to be postponed, and was again overruled.

Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle; Credit – Wikipedia

When the christening took place, George and Caroline were incensed at being repeatedly overruled. After the christening, George accused the Duke of Newcastle of acting dishonestly regarding the christening arrangements, shook his fists at him, and said, “You are a rascal but I shall find you out,” meaning get even. George had spoken English since he was a child but having lived in Hanover where German was the native language for the first thirty-one years of his life, he spoke English with a German accent. The Duke of Newcastle misunderstood George and thought he said, “I shall fight you.” The Duke quickly went to King George I and told him that his son had challenged him to a duel.

King George I summoned his cabinet for advice. A group of ministers was sent to George asking if the allegations were true. George denied he had challenged Newcastle to a duel, explained he had said “find” and not “fight” and further explained Newcastle had disrespected him by insisting he be a godfather when he knew it was against George’s wishes. When the ministers told George that Newcastle had been asked to be a godfather by the command of the king, George replied that while he respected his father, he did not believe it.

Within days, King George I ordered his son, the Prince of Wales, to leave St. James’ Palace. The Prince of Wales was further ordered to leave his children at St. James’ Palace in the custody of the king. The Princess of Wales was allowed to freely visit her children but her husband had to give notice. George appealed to the courts for his children to be returned to him but he was told that according to British law, royal grandchildren belonged to The Crown. Most people in political and court circles felt that King George I overreacted.

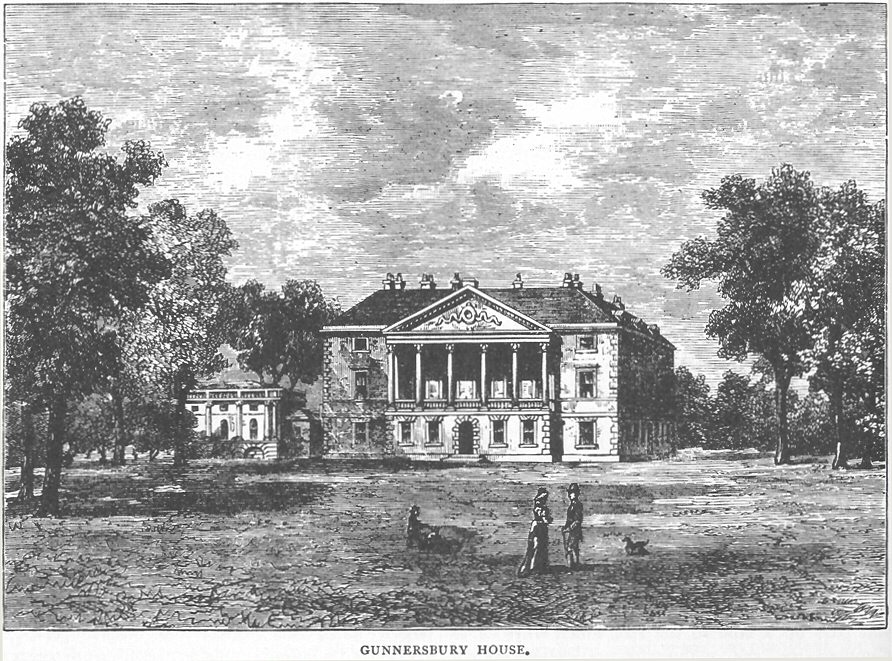

The Prince and Princess of Wales needed a residence and they moved into Leicester House in Leicester Square, London which became their chief residence for the rest of King George I’s reign. After two years, the Princess of Wales acted as a mediator for her husband, and in cooperation with Prime Minister Robert Walpole, she finally reconciled King George I and his son.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Prince George William of Great Britain. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_George_William_of_Great_Britain [Accessed 16 Jul. 2019].

- Thegazette.co.uk. (1718). Page 2 | Issue 5615, 8 February 1718 | London Gazette | The Gazette. [online] Available at: https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/5615/page/2 [Accessed 16 Jul. 2019].

- Thegazette.co.uk. (1718). Page 2 | Issue 5616, 11 February 1718 | London Gazette | The Gazette. [online] Available at: https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/5616/page/2 [Accessed 16 Jul. 2019].

- Van der Kiste, J. (2013). King George II and Queen Caroline. New York: The History Press.

- Van Der Kiste, John. The Georgian Princesses. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing, 2000. Print.

- Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell, 1996. Print. London: Cassell, 1996. Print.