by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2017

Credit – Wikipedia

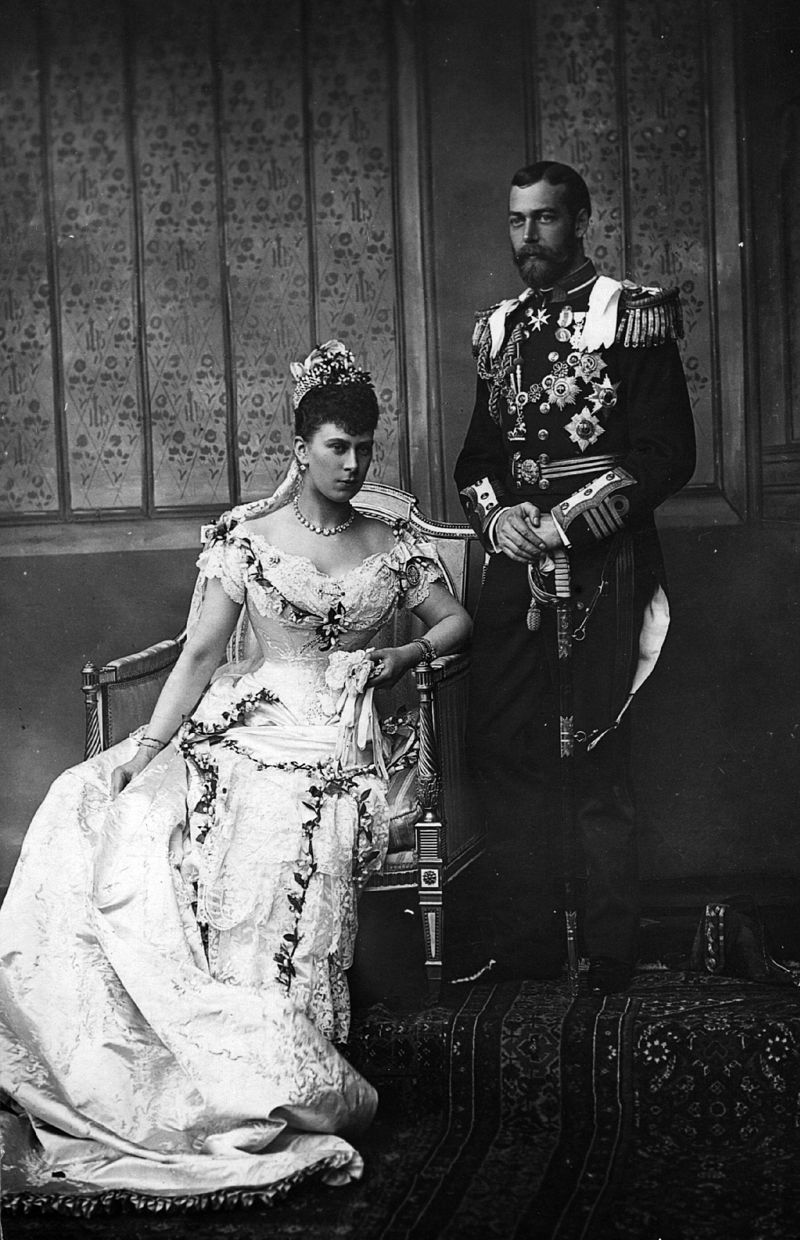

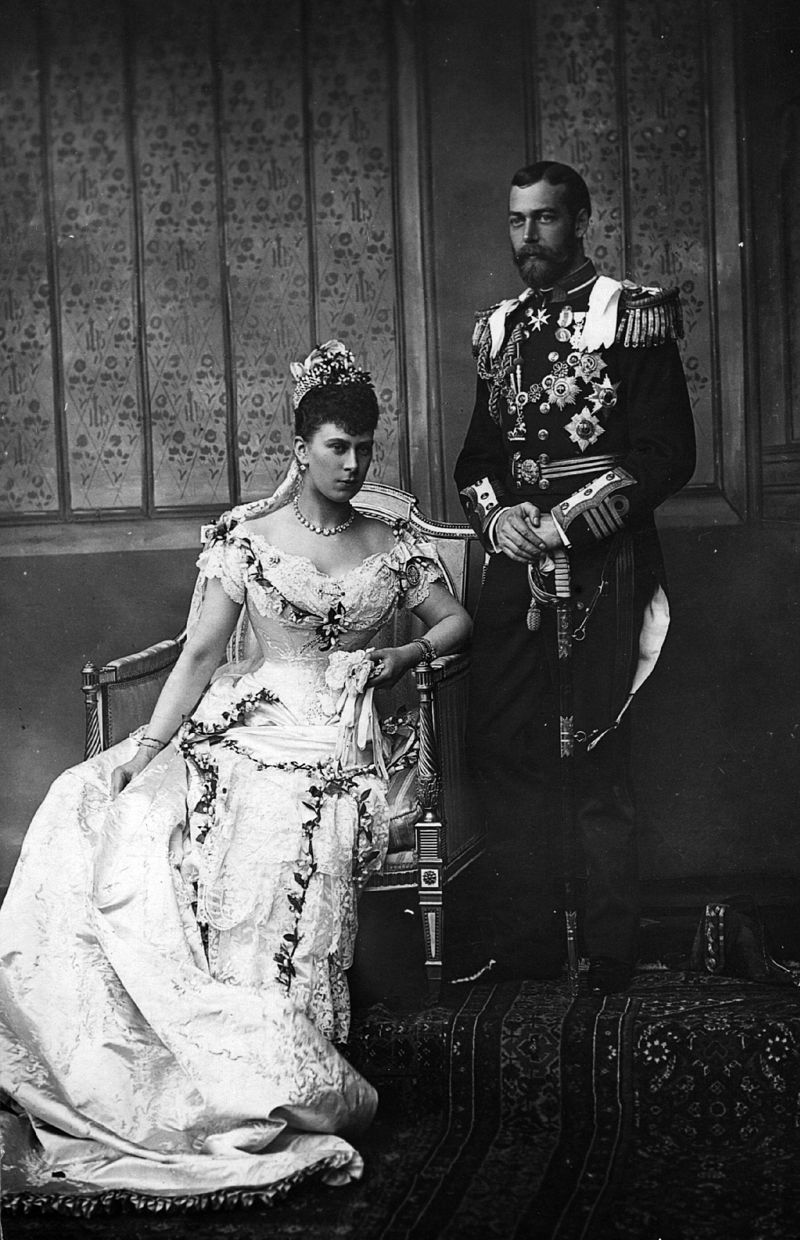

Prince George, Duke of York (the future King George V of the United Kingdom) and Princess Victoria Mary of Teck were married on July 6, 1893, at the Chapel Royal at St. James’ Palace in London, England.

Prince George’s Family

HRH Prince George Frederick Ernest Albert was born on June 3, 1865, at Marlborough House, London. His parents were Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), known as Bertie, and Alexandra of Denmark, known as Alix. Bertie’s sister Vicky, the Crown Princess of Prussia, had helped in the matchmaking. Bertie and Alix were married on March 10, 1863, at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor. Queen Victoria sorrowfully watched the ceremony from the Royal Closet, still blaming Prince Albert’s death in 1861 on a trip the ailing Albert had made to Oxford to sort out Bertie’s early sexual adventures.

HRH Prince George Frederick Ernest Albert was born on June 3, 1865, at Marlborough House, London. His parents were Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), known as Bertie, and Alexandra of Denmark, known as Alix. Bertie’s sister Vicky, the Crown Princess of Prussia, had helped in the matchmaking. Bertie and Alix were married on March 10, 1863, at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor. Queen Victoria sorrowfully watched the ceremony from the Royal Closet, still blaming Prince Albert’s death in 1861 on a trip the ailing Albert had made to Oxford to sort out Bertie’s early sexual adventures.

Bertie and Alix had six children: Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, known as Eddy (1864) who died in 1892 unmarried but engaged to Mary of Teck, George V (1865), Louise (1867) later Princess Royal who married the first Duke of Fife, Victoria (1868) who never married and served as her mother’s companion, Maud (1869) who married Prince Carl of Denmark (later King Haakon of Norway), and John who was born and died in 1871.

During their marriage, Bertie had many mistresses which Alix forced herself to accept without protest. The couple remained on friendly and affectionate terms throughout their marriage. While Bertie was on his deathbed, Alix summoned his last mistress Alice Keppel (the great-grandmother of Camilla, HRH The Duchess of Cornwall) so she might say goodbye. After Bertie died, Alix remarked, “Now at least I know where he is.”

George was related to many other royals. Through his father, he was the first cousin to Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia, Queen Marie of Rumania, Queen Sophie of Greece, Queen Ena of Spain, Crown Princess Margaret of Sweden, and was a brother to Queen Maud of Norway. Through his mother, he was the first cousin to King Christian X of Denmark, Emperor Nicholas II of Russia, King Constantine I of Greece and King Haakon VII of Norway.

Sources:

“Brewer’s British Royalty” by David Williamson

Royal Genealogies –Menu, http://ftp.cac.psu.edu/~saw/royal/royalgen.html

Directory of Royal Genealogical Data, http://www.dcs.hull.ac.uk/public/genealogy/royal/

Princess Mary’s Family

Her Serene Highness Princess Victoria Mary Augusta Louise Olga Pauline Claudine Agnes of Teck was born at Kensington Palace, London on May 26, 1867. Mary’s mother was HRH Princess Mary Adelaide, the youngest child of HRH Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge (the seventh son and tenth child of King George III and Queen Charlotte) and HRH Princess Augusta of Hesse-Cassel. The new princess was known as Mary or May.

Princess Mary Adelaide weighed approximately 250 pounds and was affectionately known as “Fat Mary.” Her first cousin Queen Victoria wrote of her, “Her size is fearful. It is really a misfortune.” Princess Mary Adelaide, however, was high-spirited and full of life and was adored by the Victorian public who called her “The People’s Princess.”

Mary’s father was His Serene Highness Prince Francis of Teck, the product of a morganatic marriage. Prince Francis’ father, Duke Alexander of Württemberg, was once heir to the throne of Württemberg. However, Duke Alexander contracted a morganatic marriage (marriage to a person of a lower rank) to a Hungarian countess, Claudine Rhedey. Alexander lost his rights to the throne and his children lost the right to use the Württemberg name. Francis’ cousin King Karl of Württemberg eventually elevated him to the more important Germanic title of Duke of Teck.

“Fat” Mary Adelaide (age 33) and genealogically-tainted Francis (age 29) married on June 12, 1866, at Kew Palace, London. Mary Adelaide and Francis had a happy marriage but had chronic financial problems due to Mary Adelaide’s extravagance and generosity. Queen Victoria gave them an apartment at Kensington Palace where their four children were born: Mary (1867), Adolphus (1868) who became the second Duke of Teck and married Lady Margaret Grosvenor, daughter of the first Duke of Westminster, Francis (1870) who died unmarried in 1910, and Alexander (1874) who married Princess Alice of Albany, the daughter of Prince Leopold, the youngest son of Queen Victoria. During World War I in 1917, when British royals were anglicizing names and titles, Adolphus became the Marquess of Cambridge and Alexander became the Earl of Athlone. Both Adolphus and Alexander adopted the surname Cambridge.

Sources:

“Queen Mary’s Photograph Album” edited by Christopher Warwick

“Brewer’s British Royalty” by David Williamson

Royal Genealogies –Menu, http://ftp.cac.psu.edu/~saw/royal/royalgen.html

Directory of Royal Genealogical Data, http://www.dcs.hull.ac.uk/public/genealogy/royal/

Prince Eddy: Princess Mary’s First Fiancé

Prince Albert Victor Christian Edward (1864-1892) was the oldest son and eldest child of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) and Alexandra of Denmark. He was known in the family as Eddy. George was his younger brother. Prince Eddy was second in line to the throne held by his grandmother Queen Victoria.

Prince Albert Victor Christian Edward (1864-1892) was the oldest son and eldest child of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) and Alexandra of Denmark. He was known in the family as Eddy. George was his younger brother. Prince Eddy was second in line to the throne held by his grandmother Queen Victoria.

Eddy was backward and lazy. He was an apathetic student and received very little education. He was primarily interested in pursuing pleasure which often led him into trouble. His lack of concentration on anything serious caused great concern in his family. There have been suggestions that Eddy was homosexual and frequented a notorious male brothel in Cleveland Street, London. A theory purported that Eddy was Jack the Ripper, but there is no real evidence to support this theory.

Eddy’s family decided that finding a suitable wife might help correct his attitude and behavior. Eddy proposed to his cousin Alix of Hesse and by Rhine (later Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia) but was rejected by her. Eddy then fell head over heels for French Catholic Princess Hélène of Orléans, who returned his love. However, Hélène’s father, the Comte de Paris, refused to allow his daughter to convert to Anglicanism and forbade the marriage.

It was at this time that, unbeknownst to her, Mary was considered the most suitable bride for Eddy. Eddy offered no resistance to this suggestion. Mary had been brought up to revere the monarchy and to be proud that she was a member of the British Royal Family. The fact that Mary’s father was a product of a morganatic marriage could have presented difficulties for her in the marriage market. Despite the shortcomings Eddy might have, Mary felt it was her duty to marry him.

Eddy proposed to Mary during a ball on December 3, 1891. The engagement was announced three days later and the wedding was set for February 27, 1892. The engagement was met with disdain by some German relatives who felt that dignified, well-educated Mary was unequal in rank due to her grandfather’s morganatic marriage. However, Queen Victoria approved wholeheartedly of the marriage.

In the midst of the wedding preparations, Eddy developed a high fever on January 7, 1892, at Sandringham. His sister Victoria and other household members already had been ill with influenza, which Eddy also developed. Two days later, his lungs became inflamed and pneumonia was diagnosed. In his delirium, Eddy frequently shouted out the name “Hélène.”

In the early morning hours of January 14, 1892, a chaplain was summoned to Eddy’s bedroom at Sandringham. There, surrounded by his parents, the Prince and Princess of Wales, his brother George, his sisters Louise, Victoria, and Maud, his fiancée Mary, and her mother the Duchess of Teck, Eddy died at 9:35 a.m. Eddy’s funeral was held at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor and he is buried in the Albert Memorial Chapel, Windsor. Mary’s wedding bouquet of orange blossoms lay on his coffin.

Sources:

“Royal Weddings” by Dulcie M. Ashdown

“Queen Mary” by James Pope-Hennessey

“Queen Mary’s Photograph Album” edited by Christopher Warwick

“Brewer’s British Royalty” by David Williamson

The Engagement

After the death of Prince Eddy, Mary and George spent much time together. As time passed and their common grief eased, there was hope that a marriage might take place between them. George proposed to Mary beside a pond in the garden of his sister Louise’s home, East Sheen Lodge, on April 29, 1893. The engagement was announced on May 3, 1893, with the blessing of Queen Victoria.

After the death of Prince Eddy, Mary and George spent much time together. As time passed and their common grief eased, there was hope that a marriage might take place between them. George proposed to Mary beside a pond in the garden of his sister Louise’s home, East Sheen Lodge, on April 29, 1893. The engagement was announced on May 3, 1893, with the blessing of Queen Victoria.

The Trousseau

Mary of Teck choosing her Wedding Trousseau by Arthur Hopkins May 1893

Mary already had a trousseau made in preparation for her wedding to Eddy. However, that trousseau had fallen out of fashion and would have been considered bad luck to use, so a new trousseau was necessary. To the rescue of the Tecks, always in financial crisis, came Mary’s aunt, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Augusta, the sister of Mary’s mother). Aunt Augusta and her husband gave Mary £1000 for the purchase of a new trousseau. The new trousseau, made by English dressmakers Linton and Curtis, Scott Adie, and Redfern, included 40 outdoor suits, 15 ball dresses, five tea gowns, bonnets, shoes, gloves, traveling capes, traveling wraps, and driving capes.

Sources:

“Queen Mary by James Pope-Hennessey

The Wedding Dress

Mary visited Queen Victoria before the ceremony, who described Mary’s dress in her diary: “Her dress was very simple of white satin with a silver design of roses, shamrocks, thistles, and orange-flowers interwoven. On her head, she has a small wreath of orange-flowers, myrtle and white heather surmounted by a diamond necklace I gave her, which also can be worn as a diadem, and her mother’s wedding veil.”

Mary visited Queen Victoria before the ceremony, who described Mary’s dress in her diary: “Her dress was very simple of white satin with a silver design of roses, shamrocks, thistles, and orange-flowers interwoven. On her head, she has a small wreath of orange-flowers, myrtle and white heather surmounted by a diamond necklace I gave her, which also can be worn as a diadem, and her mother’s wedding veil.”

Actually, Mary’s dress was far from simple. The satin brocade had been specially woven into national symbols and true love knots in silver. The bodice was cut to Mary’s figure and the front of the skirt was left open to reveal a plain satin slip. The overskirt was decorated with lace and sprays of orange blossoms. The long silk veil interwoven with May blossoms, originally made for Mary’s wedding to Eddy, was replaced with the Duchess of Teck’s wedding veil. This veil, which was little more than a short lace scarf, was secured with a diamond tiara.

Sources:

“Queen Mary” by James Pope-Hennessey

“Queen Mary’s Photograph Album” edited by Christopher Warwick

The Bridesmaids

Ten bridesmaids had been selected. At least three of the bridesmaids wished they were in Mary’s shoes.

- Princesses Victoria of Wales, sister of the groom

- Princess Maud of Wales, sister of the groom

- Princesses Victoria Melita of Edinburgh, first cousin of the groom

- Princess Alexandra of Edinburgh, first cousin of the groom

- Princess Beatrice of Edinburgh of Edinburgh, first cousin of the groom

- Princesses Margaret of Connaught, first cousin of the groom

- Princess Patricia of Connaught, first cousin of the groom

- Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg, first cousin of the groom

- Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, first cousin of the groom

- Princess Alice of Battenberg, daughter of the groom’s first cousin Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine

Back row: Princess Alexandra of Edinburgh, Princess Helena of Schleswig-Holstein, Princess Victoria-Melita of Edinburgh, Prince George, Duke of York, Princess Victoria of Wales, Princess Maud of Wales

Back row: Princess Alexandra of Edinburgh, Princess Helena of Schleswig-Holstein, Princess Victoria-Melita of Edinburgh, Prince George, Duke of York, Princess Victoria of Wales, Princess Maud of Wales

- In the middle: Princess Alice of Battenberg, Princess Margaret of Connaught, Princess Mary of Teck, Duchess of York

- Front row: Princess Beatrice of Edinburgh, Princess Victoria-Eugenie of Battenberg, Princess Patricia of Connaught

Sources:

“Queen Mary” by James Pope-Hennessey

“Brewer’s British Royalty” by David Williamson

The Wedding Guests

The Groom’s Family

- Queen Victoria, the groom’s paternal grandmother

- The Prince and Princess of Wales, the groom’s parents

- Princess Louise, Duchess of Fife and the Duke of Fife, the groom’s sister and her husband

- Princess Victoria of Wales, the groom’s sister

- Princess Maud of Wales, the groom’s sister

- The Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh, the groom’s paternal uncle and aunt

- Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh, the groom’s first cousin

- Princess Alexandra of Edinburgh, the groom’s first cousin

- Princess Beatrice of Edinburgh, the groom’s first cousin

- The Duke and Duchess of Connaught, the groom’s paternal uncle and aunt

- Prince Arthur of Connaught, the groom’s first cousin

- Princess Margaret of Connaught, the groom’s first cousin

- Princess Patricia of Connaught, the groom’s first cousin

- Prince and Princess Henry of Prussia, the groom’s first cousins

- Princess and Prince Louis of Battenberg, the groom’s first cousin and her husband

- Princess Alice of Battenberg, the groom’s first cousin once removed

- Princess and Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, the groom’s paternal aunt and uncle

- Prince Albert of Schleswig-Holstein, the groom’s first cousin

- Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, the groom’s first cousin

- Princess Louise, Marchioness of Lorne and the Marquess of Lorne, the groom’s paternal aunt and uncle

- Princess and Prince Henry of Battenberg, the groom’s paternal aunt and uncle

- Prince Alexander of Battenberg, the groom’s first cousin

- Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg, the groom’s first cousin

- King Christian IX and Queen Louise of Denmark, the groom’s maternal grandparents

- Prince Valdemar of Denmark, the groom’s maternal uncle

- Tsarevich Nicholas of Russia, the groom’s first cousin

- The Hereditary Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, the groom’s half-second cousin

- Prince Albert of Belgium, the groom’s paternal second cousin once removed

- Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the groom’s paternal second cousin once removed

- Countess Feodora Gleichen, the groom’s second cousin

- Countess Helena Gleichen, the groom’s second cousin

- Countess Victoria Gleichen, the groom’s second cousin

The Bride’s Family

- The Duke and Duchess of Teck (Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge), the bride’s parents

- Prince Adolphus of Teck, the bride’s brother

- Prince Francis of Teck, the bride’s brother

- Prince Alexander of Teck, the bride’s brother

- Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, the bride’s maternal uncle

- Augustus FitzGeorge, the bride’s cousin

- The Grand Duchess (Princess Augusta of Cambridge) and the Grand Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the bride’s maternal aunt and uncle

Other Foreign Royalty

- Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar and Princess Edward of Saxe-Weimar

- HH the Maharaja of Bhavnagar

- HH the Raja of Kapurthala

- HH the Thakur Sahib of Morbi

- HH the Thakur Sahib of Gondal

Envoys and Ambassadors

- Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, representing HM the King Wilhelm II of Württemberg

- Baron Egor Egorovich Staal, HE the Russian Ambassador and Baroness Staal

- Paul von Hatzfeldt, HE the German Ambassador

- HE the Turkish Ambassador

- Count Franz Deym, HE the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador and Countess Deym

- Count Tornielli, HE the Italian Ambassador and Countess Tornielli

- HE the Spanish Ambassador

- Thomas F. Bayard, HE the United States Ambassador and Mrs. Bayard

- Mr. Solvyns, HE the Belgian Minister and Mrs. Solvyns

- Mr. Bille, HE the Danish Minister and Mrs. de Bille

- Luís Pinto de Soveral, HE the Portuguese Minister

- HE the Romanian Minister

- Mr. Romanos, The Greek Chargé d’Affaires and Mrs. Romanos

Politicians

- William Gladstone, The Prime Minister and First Lord of the Treasury and Mrs. Gladstone

- Farrer Herschell, 1st Baron Herschell, The Lord Chancellor and Lady Herschell

- Sir William Vernon Harcourt, The Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lady Harcourt

- George Shaw-Lefevre, 1st Baron Eversley, The Chief Commissioner of Works and Lady Constance Shaw-Lefevre

- John Wodehouse, 1st Earl of Kimberley, The Lord President of the Council and Secretary of State for India and the Countess of Kimberley

- H. H. Asquith, The Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, The Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Henry Campbell-Bannerman, The Secretary of State for War and Mrs. Campbell-Bannerman

- John Poyntz Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer, The First Lord of the Admiralty and Countess Spencer

- Sir George Otto Trevelyan, 2nd Baronet, The Secretary of State for Scotland and Lady Trevelyan

- John Morley, The Chief Secretary for Ireland

- John Bryce, The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Mrs. Bryce

Royal Household

- Gavin Campbell, 1st Marquess of Breadalbane, Lord Steward

- Charles Robert Wynn-Carrington, The Lord Carrington, Lord Chamberlain

- Sir Patrick Grant, Gold Stick-in-Waiting

- George Venables-Vernon, 7th Baron Vernon, Captain of the Honourable Corps of Gentlemen-at-Arms

- William Edwardes, 4th Baron Kensington, Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard

- Edwyn Scudamore-Stanhope, 10th Earl of Chesterfield, Treasurer of the Household

- George Leveson-Gower, Comptroller of the Household

- The Right Honourable Charles Spencer, Vice-Chamberlain of the Household

- John Clayton Cowell, Master of the Household

- Thomas Lister, 4th Baron Ribblesdale, Master of the Buckhounds

- Anne Emily Innes-Ker, The Dowager Duchess of Roxburghe, Acting Mistress of the Robes

- Jane Spencer, Dowager Baroness Churchill, Lady of the Bedchamber

- Francis Robert Stonor, 4th Baron Camoys, Lord-in-Waiting

- Sir Albert Woods, Garter Principal King of Arms

- Charles Harbord, 5th Baron Suffield, Lord-in-Waiting to the Prince of Wales

- Charles John Colville, 1st Viscount Colville of Culross, Chamberlain to the Princess of Wales

Clergy

- The Archbishop of Canterbury

- Frederick Temple, The Bishop of London

- Randall Davidson, The Bishop of Rochester

Other Guests

- Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal

- Frances Osborne, The Duchess of Leeds

- Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire and Duchess of Devonshire

- John Manners, 7th Duke of Rutland and Duchess of Rutland

- William Montagu Douglas Scott, 6th Duke of Buccleuch and Duchess of Buccleuch

- George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll and Duchess of Argyll

- William Cavendish-Bentinck, 6th Duke of Portland and Duchess of Portland

- James Hamilton, 2nd Duke of Abercorn and Duchess of Abercorn

- Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury and Marchioness of Salisbury

- The Marchioness of Breadalbane

- William Edgcumbe, 4th Earl of Mount Edgcumbe of Mount Edgcumbe

- Edward Bootle-Wilbraham, 1st Earl of Lathom and Countess of Lathom

- Richard Cross, 1st Viscount Cross and Viscountess Cross

- The Lady Carrington

- Hardinge Stanley Giffard, 1st Baron Halsbury and Lady Halsbury

- Lord and Lady George Hamilton

- Arthur Wellesley Peel, The Speaker of the House of Commons

- The Right Hon. George and Mrs. Goschen

- The Right Hon. Joseph and Mrs. Chamberlain

- The Right Hon. Arthur Balfour

Sources:

Wikipedia: Wedding of Prince George, Duke of York, and Princess Mary of Teck

The Wedding

The wedding was set for July 6, 1893, at the Chapel Royal, St. James’ Palace. St, George’s Chapel, Windsor, had been the choice for Mary’s planned marriage to Eddy, but it was considered inappropriate because it had been the site of Eddy’s funeral.

The wedding was set for July 6, 1893, at the Chapel Royal, St. James’ Palace. St, George’s Chapel, Windsor, had been the choice for Mary’s planned marriage to Eddy, but it was considered inappropriate because it had been the site of Eddy’s funeral.

There was much excitement about the upcoming wedding. Women’s magazines produced special editions detailing Mary’s trousseau. Crowds visited London’s Imperial Institute where royal wedding gifts were displayed for the first time.

The summer of 1893 had been hot and July 6, the wedding day, was no different. Crowds gathered in the morning along the bridal procession route on Constitution Hill, Piccadilly, and St. James Street.

At 11:30 a.m., the first of the carriage processions left Buckingham Palace. Royalty from Britain and abroad rode in twelve open state landaus driven by cream-colored horses. The bridegroom and his father left the Palace at 11:45 a.m. followed by Queen Victoria in the Glass Coach. Accompanying the Queen was her cousin, the beaming Princess Mary Adelaide, the mother of the bride. The bride’s procession came last. Mary was accompanied by her brother Adolphus.

As Mary walked down the aisle of the Chapel Royal towards George, she leaned stiffly on her father’s arm and smiled at those guests she recognized. Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury performed the ceremony and was assisted by Frederick Temple, Bishop of London, and Randall Davidson, Bishop of Rochester, and five other prelates. While exchanging vows, George gave his answers distinctly while Mary spoke quietly. After the wedding service, the royals returned in state to Buckingham Palace.

The royals feasted at round tables covered with food in a room separate from the other guests. The guests enjoyed themselves in the Ballroom where large buffet tables were set up. After the meal, there was a royal wedding “first.” Queen Victoria led George and Mary out onto the balcony at Buckingham Palace and presented them to the cheering crowds.

Sources:

“Matriarch” by Anne Edwards

Directory of Royal Genealogical Data, http://www.dcs.hull.ac.uk/public/genealogy/royal

“Royal Weddings” by Dulcie M. Ashdown

“Queen Mary” by James Pope-Hennessey

“Queen Mary’s Photograph Album” edited by Christopher Warwick

The Honeymoon

York Cottage at Sandringham

After the wedding festivities, George changed into a frock coat and top hat and Mary into a dress of cream-white poplin with gold braid and a small gold bonnet trimmed with white ostrich feathers and rosebuds. As the couple left Buckingham Palace, the wedding guests showered them with rice. Crowds cheered them as they drove down The Mall, through the City of London to Liverpool Street Station where they boarded a train to Sandringham. The couple spent their honeymoon at York Cottage on the Sandringham estate, a five-minute walk from the room where Eddy had died less than eighteen months earlier. Queen Victoria wrote to her daughter Vicky, “The young people go to Sandringham to the Cottage after the wedding which I regret and think rather unlucky and sad.”

Sources:

“Royal Weddings” by Dulcie M. Ashdown

“Queen Mary” by James Pope-Hennessey

“Queen Mary’s Photograph Album” edited by Christopher Warwick

Children of George V and Mary of Teck

George and Mary had six children:

- King Edward VIII (Duke of Windsor after his abdication) (1894-1972), married Wallis Simpson, no children

- King George VI (1895-1952), married Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, had two daughters, British Royal Family descends from this marriage

- Mary, Princess Royal (1897-1965), married Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood, had two sons

- Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester (1900-1974), married Lady Alice Montagu-Douglas-Scott, had two sons

- Prince George, Duke of Kent, (1902-1942), married Princess Marina of Greece, had two sons and one daughter

- Prince John (1905-1919)

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.