by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2015

Stained glass window in St James Church in Sutton Cheney, England where it is believed Richard III (left) attended his last Mass before facing Henry VII (right) in the Battle of Bosworth Field; Credit – Wikipedia

On August 22, 1485, at the Battle of Bosworth Field, the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the last king of the House of York and the Plantagenet dynasty, 32-year-old King Richard III of England, lost his life and his crown. The battle was a decisive victory for the House of Lancaster, whose leader Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, became the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Richard had entered the battle as a seasoned soldier, wearing a battle crown on top of his helmet. During the battle, he saw an opportunity to strike directly at Henry Tudor and his personal guard and sped off on his horse. After managing to kill Henry Tudor’s standard-bearer, Richard saw something he had not expected. Sir William Stanley changed sides. Instead of supporting Richard and the Yorkists, Stanley attacked them, helping to secure a victory for Henry Tudor and the Lancastrians.

“Bosworth Field – Clash” by Jappalang – Base map:1933 Ordnance Survey maps of Leicester, 50-year Crown copyrights have expired Terran details based on:Features modified according to File:John Pridden’s map of the Battle of Bosworth Field.jpgDeployment and movements based on:Gravett, Christopher (1999) Bosworth 1485: Last Charge of the Plantagenets, Campaign, 66, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, p. p. 47 Retrieved on 16 March 2009. ISBN: 1-85532-863-1.English Heritage Battlefield Report: Bosworth Field 1471 (PDF). English Heritage (1995). Retrieved on 2009-04-10.. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bosworth_Field_-_Clash.svg#mediaviewer/File:Bosworth_Field_-_Clash.svg

Richard was overwhelmed by Stanley’s soldiers and at some point, he took off or lost his helmet. Polydore Vergil, Henry Tudor’s official historian, wrote that “King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies.” According to Welsh poet Guto’r Glyn, the leading Welsh Lancastrian Rhys ap Thomas, or one of his men, killed the king, writing that he “killed the boar, shaved his head.” After the battle, Henry Tudor’s men were yelling, “God save King Henry!” Inspired by this, Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Debry who was married to the new king’s mother, found Richard’s battle crown and placed it on the head of his stepson saying, “Sir, I make you King of England.”

Finding Richard’s circlet after the battle, Lord Stanley hands it to Henry, Credit – Wikipedia

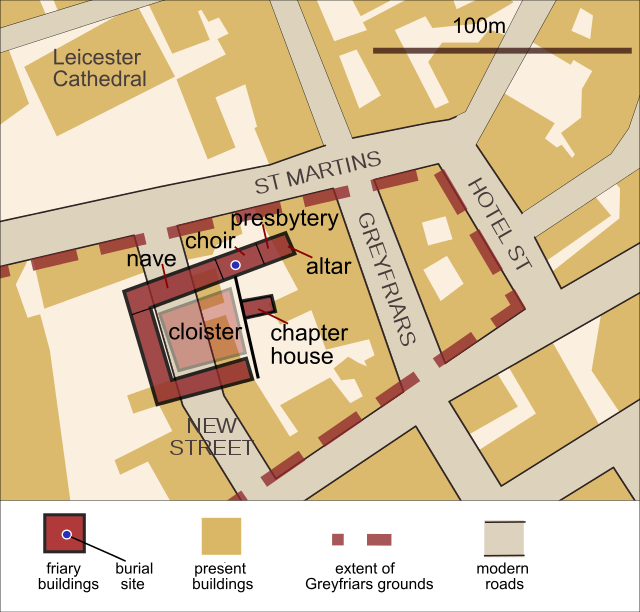

Richard’s body was stripped of its armor and carried naked across a packhorse to Greyfriars Abbey, a Franciscan abbey in Leicester, England. There the public was allowed to view the body for two days to prove that Richard was dead and the remains were then buried at the abbey church. Several years later King Henry VII paid a sum of money to the abbey to provide some kind of tomb for Richard. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, during the reign of King Henry VIII, the abbey church in Leicester, along with Richard’s burial place, was destroyed.

Richard III and his nephew Edward V, were the only English monarchs since the Norman Conquest in 1066 whose remains did not have an acknowledged burial place. There were stories that when the abbey church was destroyed Richard’s bones were dug up and thrown into the River Soar, which flows through Leicester. Another story said his coffin was used as a horse trough and that eventually the trough was broken up and used to make the steps to the cellar of the White Horse Inn.

The site of the abbey was eventually acquired by a mayor of Leicester, Robert Herrick (1540-1618), who built a mansion and gardens there. Although the abbey church and Richard’s grave were gone, it appears that it was local knowledge where Richard had been buried, and Herrick had a monument erected with an inscription, “Here lies the Body of Richard III, Some Time King of England.” There is evidence that the monument was standing in 1612 but had disappeared by 1844.

Over the years, the site changed ownership and several types of buildings were built on the site including a boys’ school and a bank. In 1915, part of the site was acquired by the Leicestershire County Council, which built new offices there. The county council moved out in 1965 when Leicestershire’s new County Hall was opened, and the Leicester City Council moved in. The rest of the site, where Herrick’s garden had once been, had been turned into a staff parking lot in 1944. In 2007, when a building on the site was demolished, archaeologists did an excavation to see if any traces of Greyfriars Abbey could be found. The excavation turned up little besides the fragment of a post-medieval stone coffin, and the results suggested that the remains of the Greyfriars Abbey were further west than had been thought.

Finding the remains of Richard III had always been an interest to the Richard III Society. In 1975, an article was published in the society’s journal suggesting that Richard’s remains were buried under the Leicester City Council’s parking lot (car park). Two historians, David Baldwin in 1986 and John Ashdown-Hill in 2005, also suggested the claim about the parking lot could prove true. Philippa Langley, the secretary of the Scottish Branch of the Richard III Society, became convinced that the parking lot needed to be investigated while doing research for a screenplay about Richard in 2005. In 2008, writer Annette Carson independently came to the conclusion that Richard’s body probably lay under the parking lot in her book Richard III: The Maligned King. Langley, Carson, and Ashdown-Hill teamed up with two Richard III Society members, Dr. David Johnson and his wife Wendy, to form a project Looking for Richard: In Search of a King. Eventually, the project gained the backing of the Leicester City Council, Leicester Promotions (responsible for tourist marketing), the University of Leicester, Leicester Cathedral, Darlow Smithson Productions (responsible for the planned TV show) and the Richard III Society. The University of Leicester Archaeological Services agreed to do the archaeological excavations.

“Greyfriars, Leicester site” by Hel-hama – Own work, based on work of RobinLeicester (Base map OS OpenData VectorMap District. Greyfriars perimeter from Billson, C. J., 1920, Medieval Leicester, facing p. 1. Edgar Backus, Leicester (Archive.org). Greyfriars Church details, University of Leicester Plan of the 2012 Archaeological dig, Mail Online, 12 Sept 2012)This vector image was created with Inkscape. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Greyfriars,_Leicester_site.svg#mediaviewer/File:Greyfriars,_Leicester_site.svg

The excavations began on August 25, 2012, and on that day, two human leg bones were discovered. Over the next several days, evidence of medieval walls and rooms was uncovered which allowed the archaeologists to determine the area of the abbey. It soon became clear that the leg bones found on the first day lay inside the east part of the church, possibly the choir, where Richard was said to have been buried. Further investigation in the area where the leg bones were found revealed more remains: the skull was found in an unusual propped-up position, consistent with the body being put into a grave that was slightly too small; the spine was curved in an S-shape; the hands were in an unusual position, crossed over the right hip, suggesting they were tied together at the time of burial. No evidence of a coffin or shroud was found and the skeleton’s position suggested that the body had been dumped into the grave.

On September 12, 2012, the archaeological team announced that the human remains could possibly be those of Richard III. Evidence of such a possibility included:

- The body was an adult male

- It was buried under the choir of the church

- Severe scoliosis of the spine, possibly making one shoulder higher than the other

- There were severe injuries to the skull

- University of Leicester: Richard III: Discovering the remains

- YouTube: BBC – Possible Remains of King Richard III Found

“Richard III burial site” by Chris Tweed – Flickr: richard iii trench 1 richard iii burial site 02. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Richard_III_burial_site.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Richard_III_burial_site.jpg

Now the scientists set to work on the remains. The DNA from Michael Ibsen, a direct descendant of Richard’s sister Anne of York, and an unnamed direct maternal line descendant matched the mitochondrial DNA extracted from the remains.

The bones were examined and the following discoveries were made:

- The base of the back of the skull had been completely cut away by a bladed weapon, which would have exposed the brain

- Another bladed weapon had been thrust through the right side of the skull to impact the inside of the left side through the brain

- A blow from a pointed weapon had penetrated the crown of the head

- Bladed weapons had clipped the skull and sheared off layers of bone, without penetrating it

- Holes in the skull and lower jaw were found to be consistent with dagger wounds to the chin and cheek.

- One of the right ribs and the pelvis had been cut by a sharp implement

- No evidence of the withered arm that afflicted the character in William Shakespeare’s play Richard III

- Severe curvature of the spine was attributed to adolescent-onset scoliosis

- The bones are those of a male with an age range estimation of 30–34; Richard was 32 when he died

On February 4, 2013, the University of Leicester confirmed that the remains were those of King Richard III.

The remains of Richard III were reburied at Leicester Cathedral on March 26, 2015. Three members of the Royal Family, The Countess of Wessex and The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester, attended the reburial. It was fitting that the Duke of Gloucester attended the reburial as his name is also Richard and Richard III was also a Duke of Gloucester. The Duke of Gloucester is Patron of The Richard III Society.

- BBC: Richard III reinterment date announced

- BBC: Roses on Richard III cortege route will highlight missing people

- BBC: Richard III: The Full Story

- Getty Images: Leicester Sees The Reinterment Of The Remains Of King Richard III

- BBC: Richard III: Leicester Cathedral reburial service for king

“Tomb of Richard III, Leicester Cathedral” by RobinLeicester – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomb_of_Richard_III,_Leicester_Cathedral.jpg#/media/File:Tomb_of_Richard_III,_Leicester_Cathedral.jpg

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

There are lots of resources and more information at:

Works Cited

- “Battle of Bosworth Field.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 7 Mar. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Bosworth_Field>.

- “Exhumation of Richard III of England.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 7 Mar. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exhumation_of_Richard_III_of_England>.

- “Greyfriars, Leicester.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 7 Mar. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greyfriars,_Leicester>.

- Jones, Dan. The Wars of the Roses: The Fall of the Plantagenets and the Rise of the Tudors. Print.

- Lisle, Leanda. Tudor: Passion, Manipulation, Murder: The Story of England’s Most Notorious Royal Family. Print.

- “Richard III of England.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 7 Mar. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_III_of_England>.

- Ross, Charles Derek. Richard III. Berkeley: U of California, 1981. Print.

- “The Discovery of Richard III.” By the University of Leicester. Web. 8 Mar. 2015. <http://www.le.ac.uk/richardiii/>.

- Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell, 1996. Print.