by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

William the Conqueror, Bayeux Tapestry; Credit – Wikipedia

King William I of England, also known as William the Conqueror, the only son of Robert I the Magnificent, Duke of Normandy, was born circa 1027-1028 at the Château de Falaise in Falaise, Duchy of Normandy (now in France). William was illegitimate as his mother Herleva of Falaise was his father’s mistress, and for that reason, he is sometimes called William the Bastard.

Normandy was a French fiefdom originally created as the County of Rouen in 911 by King Charles III “the Simple” of France for Rollo, a Viking leader whose original name may have been Hrólfr. After participating in many Viking raids along the Seine, culminating in the Siege of Paris in 886, Rollo was finally defeated by King Charles III. Rollo swore fealty to the French King and converted to Christianity. Charles then granted Rollo territories around Rouen, which came to be called Normandy after the Northmen/Norsemen, another name for Vikings. Rollo is the great-great-great-grandfather of William the Conqueror. Through William, he is an ancestor of the British Royal Family, all current European monarchs, and a great many claimants to abolished European thrones.

Counts/Dukes of Normandy before William:

Counts (Earls or Jarls) of Normandy

- Rollo (c. 846 – c. 932)

- William I Longsword (c. 893 – 942), son of Rollo

- Richard I the Fearless ( 942–996), son of William I Longsword

Dukes of Normandy

- Richard II the Good (963 – 1026), son of Richard I the Fearless

- Richard III (997/1001 – 1027), son of Richard II the Good

- Robert I the Magnificent (1000 – 1035), son of Richard II the Good

The three sons of Herleva of Falaise: William, Duke of Normandy, in the centre, Odo, the bishop of Bayeux, on the left and Robert, Count of Mortain, on the right (from the Bayeux Tapestry Scene 44; Credit – Wikipedia

William had several half-siblings:

From his mother Herleva ‘s marriage to Herluin de Conteville

- Odo, Earl of Kent, Bishop of Bayeux (circa 1030 – 1097)

- Robert, Count of Mortain, 2nd Earl of Cornwall (circa 1031–1090), married (1) Matilda, daughter of Roger de Montgomery, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, had issue; (2) Almodis, no issue

- Emma, married Richard LeGoz, Count of Avranches

- Daughter of unknown name, married William, Lord of la Ferté-Macé

Both of William’s half-brothers, Odo and Robert, were prominent during William’s reign as King of England. Odo was likely the one who commissioned the famous Bayeux Tapestry which depicts the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England and ending in the Battle of Hastings. As there are no contemporary portraits of William, the Bayeux Tapestry contains the only pictorial representations of him. The scenes of the Bayeux Tapestry and the English translation of the Latin captions can be seen at Wikipedia: Bayeux Tapestry tituli.

William had a sibling from his father Robert I the Magnificent, Duke of Normandy and his mother Herleva or possibly another concubine:

- Adelaide of Normandy, Countess of Aumale (c. 1030 – before 1090), married (1) Enguerrand II, Count of Ponthieu, had issue (2) Lambert II, Count of Lens, had issue (3) Odo II of Champagne, had issue

William’s great-aunt, Emma of Normandy, daughter of Richard I the Fearless, Duke of Normandy, was a queen consort of England, Denmark, and Norway through her marriages to Æthelred II the Unready, King of England and Cnut the Great, King of England, Denmark, and Norway. Emma was the mother of two kings, Harthacnut, King of Denmark and King of England and Edward the Confessor, King of England.

In 1034, William’s father, Robert I, went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem despite protests from some of his nobles. Before he left, Robert had his nobles swear fealty to William as his heir. Robert died in Nicaea (now in Turkey) in July 1035 as he was returning to Normandy. William was only seven or eight years old when he became William II, Duke of Normandy. Young William grew up under the protection of Alan III, Duke of Brittany, Gilbert, 2nd Count of Brionne, and Osbern the Seneschal. All three guardians were assassinated. The sons of Gilbert, 2nd Count of Brionne accompanied William to England and their descendants would become some of the most powerful families in England: English house of de Clare, the Barons FitzWalter, the Earls of Gloucester, and the Earls of Hertford. In 1047, William’s cousin Guy of Burgundy led a revolt for the control of Normandy which William successfully defeated.

In 1051 or 1052, William married Matilda of Flanders, daughter of Baldwin V, Count of Flanders and Adèle of France, daughter of King Robert II of France. The couple married without the approval of the Pope. Finally, in 1059 papal approval was received, but William and Matilda each had to found an abbey in Caen, Duchy of Normandy, now in France, as penance: the Abbaye-aux-Hommes (St. Stephen’s) and the Abbaye-aux-Dames (Holy Trinity). William and Matilda were devoted to each other and there is no evidence that William had any illegitimate children.

William and Matilda had four sons and at least six daughters. The birth order of the boys is clear, but that of the girls is not. The list below is not in birth order. It lists the sons first in their birth order and then his daughters in their probable birth order.

- Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy (1051-1054 – 1134), married Sybil of Conversano, had one son

- Richard of Normandy (circa 1054 – circa 1070), died in a hunting accident in the New Forest

- William II Rufus, King of England (1056-1060 – 1100), unmarried, killed in the New Forest

- Henry I, King of England (1068 – 1135), married (1) Matilda of Scotland, had one son and one daughter (2) Adeliza of Louvain, no children

- Agatha of Normandy died before 1074, unmarried

- Adeliza of Normandy (circa 1055 – before 1113), probably a nun at the Abbey of St Léger in Préaux, Duchy of Normandy

- Cecilia of Normandy (circa 1056 – 1127), Abbess of Holy Trinity in Caen

- Matilda of Normandy (circa 1061 – circa 1086)

- Constance of Normandy (1057-1061 – 1090, married Alan IV, Duke of Brittany, no issue

- Adela of Normandy (circa 1067 – 1137), married Stephen II, Count of Blois, had ten children including King Stephen of England

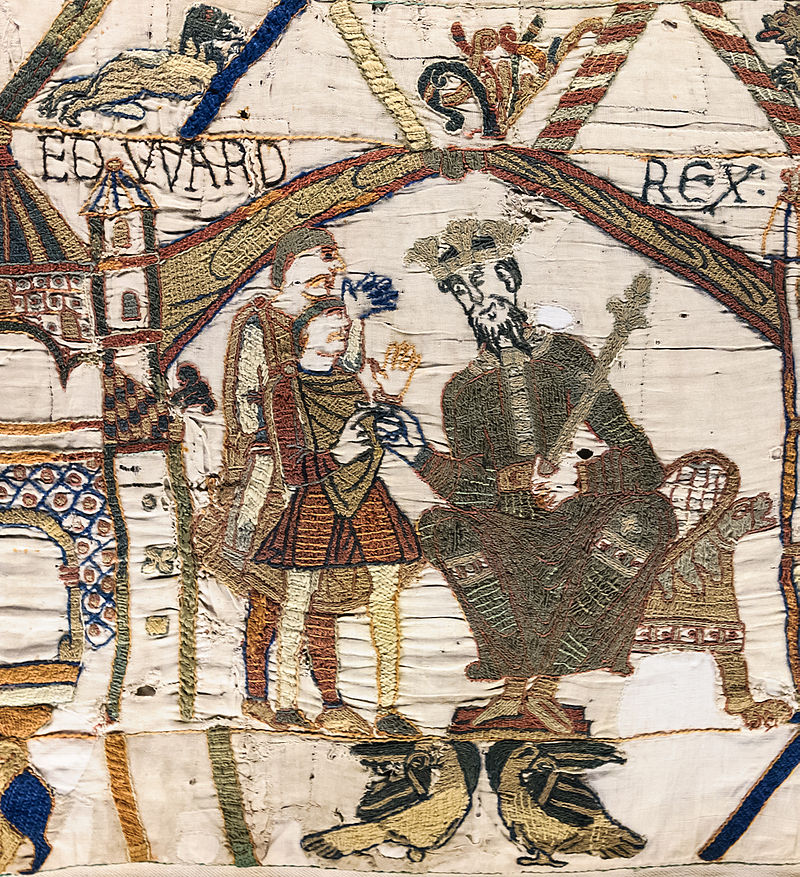

Bayeux Tapestry – Scene 1: King Edward the Confessor and Harold Godwinson at Winchester; Credit – Wikipedia

In England, Edward the Confessor, William’s first cousin once removed was King of England. Edward had married Edith of Wessex, the daughter of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, the most powerful earl in England. Edward and Edith’s marriage was childless and there was concern over the succession. At that time, succession to the throne was not entirely based upon primogeniture. The Anglo-Saxons had a king’s council called the Witan and one of the Witan’s jobs was to elect the king. There were several potential candidates to succeed Edward the Confessor.

1) Edward the Exile (1016 – 1057) also called Edward Ætheling was the son of King Edmund Ironside (King Edmund II). Edmund Ironside was the half-brother of Edward the Confessor from Æthelred II the Unready’s first marriage, so Edward the Exile was Edward the Confessor’s nephew. Edmund Ironside had succeeded his father Æthelred II (the Unready) as King of England in 1016. Edmund’s reign was short-lived. During his seven-month reign, Edmund battled against the Danish Cnut the Great for control of England. After a victory for the Danes at the Battle of Assandun on October 18, 1016, Edmund was forced to sign a treaty with Cnut which stated that all of England except Wessex would be controlled by Cnut. When one of the kings died, the other would take all of England, that king’s son being the heir to the throne. Edmund Ironside died on November 30, 1016, and Cnut became king of all England. King Cnut sent Edward the Exile to King Olaf Skötkonung of Sweden to be murdered, but instead, the king sent him to Kiev where his daughter was the queen. There he grew up in exile. Edward the Exile had the best hereditary claim to the English throne.

2) Edgar the Ætheling (c. 1051 – c. 1126) was the son of Edward the Exile. After his father’s death, Edgar had the best hereditary claim to the English throne.

3) Harald III Hardrada, King of Norway (c. 1015 – 1066) was named the heir to the childless nephew King Magnus I of Norway. Magnus and King Harthacnut of England and Denmark, Edward the Confessor’s half-brother and his predecessor, made a political agreement that the first of them to die would be succeeded by the other. As Magnus’ heir, Harald Hardrada, thought he had a claim to the English throne.

4) Harold Godwinson (c. 1022 – 1066) was the son of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, the most powerful earl in England and the brother of Edward the Confessor’s wife. Harold succeeded his father as Earl of Wessex in 1053 and he then became the most powerful person in England after Edward the Confessor, King of England.

5) William II, Duke of Normandy was the first cousin once removed of Edward the Confessor. Edward the Confessor’s mother Emma of Normandy was the sister of William’s grandfather Richard II the Good, Duke of Normandy.

Family relationships of the claimants to the English throne in 1066, and others involved in the struggle. Kings of England are shown in bold; Credit – Wikipedia

William’s marriage to Matilda of Flanders may have been motivated by his growing desire to become King of England. Matilda was a direct descendant of Alfred the Great, King of Wessex. In 1051, William visited his first cousin once removed, Edward the Confessor, King of England, and apparently Edward named William as his successor.

In 1057, Edward the Confessor discovered that his nephew Edward the Exile was still alive and summoned him to England as a potential successor. However, Edward died within two days of his arrival in England and the cause of his death has never been determined. Murder is a possibility, as he had many powerful enemies. His three children Edgar the Ætheling, Margaret, and Cristina were then raised in the court of Edward the Confessor. Margaret, known as Saint Margaret of Scotland, married King Malcolm III of Scotland and their daughter Edith married King Henry I of England, son of William.

In 1064, Harold Godwinson, the Earl of Wessex, was shipwrecked on the shores of Ponthieu and was captured by Guy I, Count of Ponthieu as the Bayeux Tapestry relates. William demanded the release of Harold, and after being paid a ransom for him, Guy delivered Harold Godwinson to William. Harold was not released from Normandy until he had sworn on holy relics to be William’s vassal and to support his claim to the throne of England.

Guy capturing Harold, scene 7 of the Bayeux Tapestry; Credit – Wikipedia

Harold swearing the oath, scene 23 of the Bayeux Tapestry; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1065, it is possible that Edward the Confessor had a series of strokes. He was too ill to attend the dedication of his greatest achievement, the church at Westminster, now called Westminster Abbey, on December 28, 1065. Edward the Confessor died several days later, on January 5, 1066. According to the Vita Ædwardi Regis, before Edward died he briefly regained consciousness and named Harold Godwinson as his heir. The Witan met the next day and selected Harold Godwinson to succeed Edward as King Harold II. It is probable that Harold was immediately crowned in Westminster Abbey.

Harold meeting Edward shortly before his death, depicted in scene 25 of the Bayeux Tapestry; Credit – Wikipedia

When William heard that Harold Godwinson had been crowned King of England, he began careful preparations for an invasion of England. During the summer of 1066, he assembled an army and an invasion fleet. Meanwhile, in England, Harold Godwinson was forced to march to Northumbria in September of 1066 to deal with an invasion by his brother Tostig Godwinson and Harald III Hardrada, King of Norway. Harold Godwinson defeated the invaders and killed Tostig Godwinson and Harold Hardrada on September 25, 1066, at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. The Norman invasion fleet sailed two days later and landed in England on September 28, 1066, at Pevensey Bay.

A scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing Normans preparing for the invasion of England; Credit – Wikipedia

While William waited for Harald III Hardrada to march south with his armies, he ordered the first of his many fortifications to be built, Pevensey Castle at the place he landed and Hastings Castle about 15 miles east along the coast. William’s army met Harold Godwinson’s army about six miles northwest of Hastings on October 14, 1066. The exact strength of the two armies is unknown, but modern estimates are around 10,000 for William and about 7,000 for Harold. The English army was composed almost entirely of infantry and some archers. The Norman army was infantry, with the rest split equally between cavalry and archers. Harold appears to have tried to surprise William, but Norman scouts found his army and reported its arrival to William, who marched from Hastings to the battlefield to confront Harold. The battle lasted from about 9 AM to dusk. Early efforts of the Normans to break the English battle lines had little effect. In response, the Normans adopted the tactic of pretending to flee in panic and then turning on their pursuers. Harold’s death, probably near the end of the battle, led to the retreat and defeat of most of his army.

The Battle of Hastings, Bayeux Tapestry Scene 52a; Credit – Wikipedia

Harold is slain, Bayeux Tapestry Scene 57; Credit – Wikipedia

Following Harold’s death in battle, the Witan elected the teenaged Edgar the Ætheling, the last of the House of Wessex, King of England. As William’s position grew stronger, it became evident to those in power that King Edgar should be abandoned and that they should submit to William. On Christmas Day 1066, William was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey. The south and east of England quickly submitted to William’s rule, but there were risings in parts of England for the next five years. The Normans lived like an army of occupation, building castles, keeps, and mottes throughout England from which they could dominate the population.

The White Tower at the Tower of London was begun by William in 1066; Photo Credit – Susan Flantzer

Anglo-Saxon lords were superseded by Norman and French lords and continental feudalism was introduced. Likewise, Anglo-Saxon bishops were replaced with Norman and French bishops, and Lanfranc of Pavia, who had served William in Normandy, became Archbishop of Canterbury and reorganized the Anglo-Saxon Church in the style of the Norman and French Churches.

Statue of Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury, from the exterior of Canterbury Cathedral; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1071, William felt England was secure enough and he could then consider the situation in Normandy which was more vulnerable to attacks from the King of France and the Count of Anjou. At Christmas 1085, William ordered the compilation of a survey of the landholdings held by himself and by his vassals throughout the kingdom, organized by counties, now known as the Domesday Book. The Domesday Book is an invaluable primary source for historians, both professional and amateur. No survey of landholdings approaching the scope and extent of Domesday Book was attempted again until 1873. The original Domesday Book is stored at The National Archives at Kew, London. In 2011, the Open Domesday site made the manuscript available online. See OPEN DOMESDAY – The first free online copy of Domesday Book

Towards the end of 1086, William returned to Normandy where the marriage of his daughter Constance was celebrated. In 1087, the French garrison at Mantes made a raid into Normandy. William retaliated by sacking the town. While he was urging on his soldiers. William’s horse stumbled and he was violently flung against his saddle pommel. He received serious internal injuries, most likely a ruptured bladder. William was taken to Priory of St. Gervais in Rouen where peritonitis developed. As he knew he was dying, William composed a letter to Lefranc, Archbishop of Canterbury stating that Normandy should go to his eldest son Robert, England should go to his second son William Rufus, and his youngest son Henry should receive money. The youngest son later became King Henry I of England. King William I the Conqueror died on September 9, 1087, aged about 59.

William was buried at the abbey he built at the time of his wedding, the Abbaye-aux-Hommes (St. Stephen’s) in Caen, Normandy (now in France). His grave was disturbed several times. In 1522, it was opened on orders of the Pope. French Huguenots desecrated the grave in 1562, leaving only William’s left thigh bone. This was thought to have been destroyed during the French Revolution, but was later found and reburied under a new grave marker in 1987.

Tomb of King William I the Conqueror of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Stone marking the grave; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

England: House of Normandy Resources at Unofficial Royalty